The line of spectators started to form at dusk, and by the time Barry Pidgeon unlocked the turnstiles there would be over 10,000 eager customers waiting to hand over their rations just to catch a glimpse of the miraculous Anastasia.

He named his rare pet after the famous Russian duchess who had been executed during the Bolshevik revolution. Her body was never found, but sightings were reported for years to come, giving the people hope that against all odds she had somehow survived. The same was true of his Anastasia. After the Great Die Off of the late 21st century there were only rumors of living, breathing creatures, but against all odds Barry rediscovered animal life in Old Manhattan.

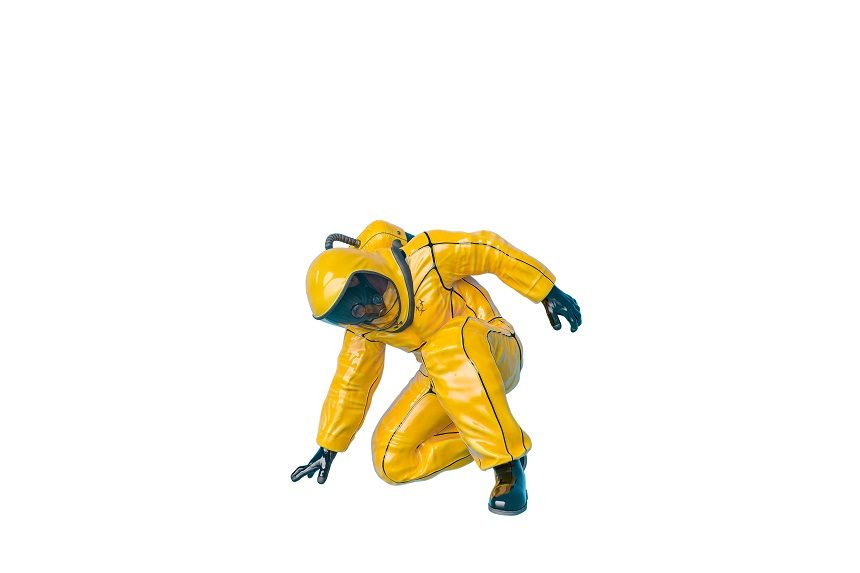

He was a copper wire scavenger in the once great metropolis. After North Korea blasted the city back to the stone age it wasn’t uncommon to see brave men like Barry dressed in nuclear immersion suits, popping potassium iodide tablets through their Isreali-made respirators as they scoured the ruins for recyclables.

Barry hadn’t breathed Earth’s oxygen since he was a boy. No one had. In the arms race of the Second Cold War nearly every country in the world developed their own nuclear weapons, and on that fateful day, September 11th, 2092 when President Jack Black the 3rd pushed the big red button in the war room, nearly every country followed suit and detonated their bombs. The air around him had changed from a balanced cocktail of three parts nitrogen, one part oxygen, with a splash of argon and carbon dioxide to a dangerous slurry of nitrogen, argon, carbon dioxide, and toxic radiation.

Plants died. The “machine” that turned carbon dioxide into oxygen was no more. Animals suffocated and burned to a crisp. That “lucky old sun” that used to “roll around heaven all day” now punished the earth. No oxygen meant no ozone and so there was little to block the UV rays from penetrating fur and flesh. No crops. No meat. Nothing but the factory made Almost bars that doomsday preppers squirreled away in their underground bunkers. Barry still remembered the classic commercials of his youth.

“Is it food?” “Almost!”

And Barry was lucky to have paranoid conspiracy theorists for parents. Sure it meant that he was never vaccinated against easily avoidable viruses and that he spent most of his homeschool hours learning to disassemble and reassemble machine guns, but when the atomic dust cleared, he and his family poked their heads out of their asbestos-lined concrete bunker to live another day.

He had lived another 7,372 days and now he was 27 years old. His last memory of a real life pet were his chickens Tyson, Drumstick, and Nugget. They too survived the blast but they didn’t survive his father’s cravings for meat after all the factory farms disappeared in a flash. Nuclear holocaust is abhorrent, but eating your pets is just depressing.

And then one fateful day when he was ripping copper wire out of the walls at 725 5th Avenue, he just happened to open an apartment door to find Anastasia cowering in a dark corner.

It didn’t seem real at first. Like waking up to the Virgin Mary sitting at the foot of your bed or buttering a piece of toast only to discover the face of Jesus staring up from the crisp slice of Wonderbread. This was a miracle. A living, breathing animal existing, without assistance, in the poisonous air.

He worried that the precious creature would scamper away and would be lost in the ruins, so he moved cautiously into the former living room. He risked breaking the seal of his containment suit to shake out a couple of crumbs of an Almost bar. The momentary exposure burned his skin but it was worth it. The innocent little animal looked up at him with the most expressive eyes as if to say “Thank you, Barry. I’ve been waiting for you” and she proceeded to happily nibble away on the genetically modified protein packed morsels.

He found a shoebox still intact, a miracle in and of itself, and lured his new pet into its new home. He couldn’t focus on his work, opening the lid a dozen times an hour to marvel at his discovery. And for the first time in decades he felt something like hope. He thought back on all that Russian literature that his parents had been obsessed with and his mind jumped to the story of the Grand Duchess Anastasia Romanov. Once believed to be dead. But no more. His Anastasia. Once believed to be extinct. But no more.

The exhibition hall was a reclaimed circus tent that Barry had scavenged from Coney Island. Its thick canvas blocked most of the UV rays and although spectators still had to suck on their oxygen tanks, they could at least remove their face shields long enough to take a look at his famed pet.

He employed weavers and tinkerers to manufacture a whole line of Anastasia merchandise and peddlers sold these momentos to those waiting in line. Cash money was worthless. During the depths of the great toilet paper shortage of 2095 armed thugs actually robbed banks just to use the greenbacks to wipe with. So people paid with scrap for the plush Anastasia dolls and Anastasia ammo with a caricature of her face stamped on the full metal jackets and the Anastasia brand water filters (where you’d suck up polluted water through her adorable body).

It was a bartering society, so the price varied based on demand and on the customer’s attitude. If you were polite and aluminum siding was booming, an 8-foot by 4-foot panel might score you an Anastasia canteen or an Anastasia fragmentation grenade. It all depended on the market.

The bleached white T.P. of Barry’s youth was worth its weight in gold and occasionally an eccentric businessman would arrive in the early morning hours to try to purchase Anastasia with a factory sealed 24-pack of Charmin from the year 2000. It was tempting because even with all of his fortune and fame, Barry still wiped with machine washable burlap like everybody else. But he couldn’t do it. Not only was Anastasia profitable, she was his pet and he loved her.

And he loved watching the way that children reacted when they got to see her. Their faces lit up. They would squeal with excitement. They would insist that Anastasia was looking at them, that she smiled at them, that she winked her eye at them. The moving walkway would escort them on to yet another gift shop and they would crane their necks until Anastasia was completely out of sight. They’d hug their plush Anastasia dolls to their chests and beg their parents to get back in line for another chance to see the World’s Last Surviving Wild Animal.

Most adults remembered pets and zoos. But telling a child about a puppy or a kitten or a chicken was like telling previous generations about pterodactyls and velociraptors. These were mythical creatures, and even in the virtual reality simulators, the children couldn’t wrap their minds around what it must have been like to go to sleep with a real life pet.

For a brief time after the die out, former jockeys from the now-defunct race tracks could make good money dressing up as oversized cats and dogs for the rich. For a few thousand an hour you could walk and groom and feed your rented “pet.” But soon radiation suits were required for survival, and no one wanted to play with a human posing as a fake dog wrapped in rubber and lead.

Every night Anastasia slept on Barry’s chest, inside his radiation suit. She would circle a few times and then settle into his tufts of hair and drift off to the Land of Nod. And this is how the accident occured. How Barry crushed his beloved Anastasia and deprived the world of its last living pet.

He was having the same old nightmare. The bombs were falling. The other children in the bunker were screaming. And Indigo Rain, one of the other mothers who had agreed to wait out the massacre with his parents, was losing her mind. She seemed to levitate up the iron ladder and before Barry’s parents could stop her, she was cranking open the hatch. She was screaming about just wanting to see the trees. Just one last look before the trees were gone. And at that moment a flash melted the skin right off her face …

He woke up sweating on the floor. In his dream he had thrown himself to the ground to protect his own face. And in reality, he had also thrown himself to the ground. He felt something wet on his chest and before he moved a muscle, he knew. Anastasia had been crushed. Her vital fluids were running down his sternum. He pushed himself up and she clung to his chest hair. He began to sob as he lay back on the bed and lifted his suit to give her some space, hoping to see her breathe.

She looked up at him. Those dark black eyes seemed to plead with him. They said “Why?” They cried “How could you?” And her thorax quivered. And she stretched out a single wing. And her antennae twitched. Once. Twice. And she was still. And the last living thing … the last cockroach, in the whole wide world, the very last one, was dead.

Featured image: Shutterstock, DM7

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Wow Brian! This IS quite a tale you’re telling here. However, it seems less ‘far out’ with each passing day in 2020. I like your clever, descriptive writing style combined with original imaginative ideas that don’t go over the edge. It makes you wonder how much of it will turn out to be unwittingly accurate after all by the 2090’s, or even decades sooner with global warming run amok. The next few months may provide some strong clues. Fasten your seat belt.