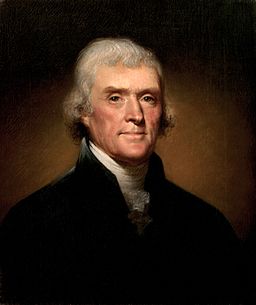

When it comes to American politics, few topics have been as widely discussed in the past few years as impeachment. The impeachment process in the United States begins with charges brought against a public office holder; at the federal level, charges rise from the House of Representatives and move to a trial in the Senate. To date, three presidents have been impeached by the House: Andrew Johnson (1868), Bill Clinton (1998), and Donald Trump (2019); eventually, all three were acquitted by the Senate. However, impeachment proceedings aren’t exclusively limited to the president. In fact, a Supreme Court Justice was once impeached by the House. He was Samuel Chase, a signer the Declaration of Independence, and one of the primary advocates for his removal was a fellow signatory, a man named Thomas Jefferson.

Chase was born in Maryland in 1741. He grew up to study law and began to practice in Annapolis around 1761. In 1762, he married Anne Baldwin; during that same year, an Annapolis debate group called the Forensic Club kicked him out for what it called “extremely irregular and indecent behavior” (this turned out to be as a result of insulting colleagues with “impious language”). Samuel and Anne Chase had seven children before her death in 1776; Chase would later marry Hannah Kitty in 1784 and have two more children.

The lawyer’s transition to public office began in 1764, when he was elected to the Maryland General Assembly. By 1766, he was openly feuding with local loyalists to the British Crown. He opposed the Stamp Act and co-founded a local branch of the Sons of Liberty with his friend William Paca. Soon after, he and Paca became delegates to the Continental Congress. In 1776, both men signed the Declaration of Independence. Chase got wrapped up in a scandal in 1778 as party to an attempt to corner the flour market with insider Congressional information; Maryland did not send him back to the Congress as a result. After the Revolutionary War, Chase settled in Baltimore. He was appointed to the District Criminal Court in Baltimore, and later moved up to the role of Chief Justice of the Maryland General Court. In 1796, President George Washington appointed Chase to the United States Supreme Court as an associate justice; he was ninth nominee to the bench.

A few years later, third president Thomas Jefferson felt that the courts had become too powerful, and worked to limit their authority. Targeting Federalist opponents, Jefferson’s allies in Congress took steps to remove certain judges from their posts. Chase made himself more visible in Jefferson’s sights by publicly disagreeing with him on cases; the president also felt that Chase was failing at impartiality, acting more like a prosecutor than as a judge (particularly in the case of Thomas Cooper, who had been jailed under the Alien and Sedition Acts for an article he wrote attacking John Adams). Chase also spoke out about people whom he personally thought should be charged. This was too much for Jefferson, who felt that Chase had veered out of his lane and into unconstitutional behavior.

John Randolph, a Congressman from Virginia, instigated impeachment in the House of Representatives. By 1803, Congress served the Justice with eight articles of impeachment that covered everything from libel to ill temper. The House voted on March 12, 1804, and Chase was impeached by a count of 73-32. Randolph led the trial in the Senate, which began on February 9, 1805. However, it soon became clear that the collected charges were all related to cases that Chase worked on in lower courts; at the time Supreme Court justices still presided in circuit courts, as well. The Senate voted to acquit him on March 1, 1805.

Following the trial in the Senate, Chase remained in the Supreme Court until his death in 1811. The fallout from the case turned out to be positive, as it established how impeachment proceedings commenced, set a precedent that the judiciary should not be partisan, and suggested limits that prevent judges from acting like prosecutors. It also set informal limits on the rationale of impeaching a judge, more or less suggesting that there needs to be some kind of ethical or legal breach on behalf of the judge in order to bring charges.

Chase cuts an interesting figure in history. By pushing the boundaries of his position, he helped define how subsequent generations view and establish those boundaries. His case also set a precedent that attempts to eliminate the bringing of impeachment in a strictly partisan manner, forcing the representatives involved to produce more concrete charges. Chase remains the only Supreme Court justice to face the proceeding to date.

Featured image: The United States Supreme Court (Steven Frame / Shutterstock)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now