This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

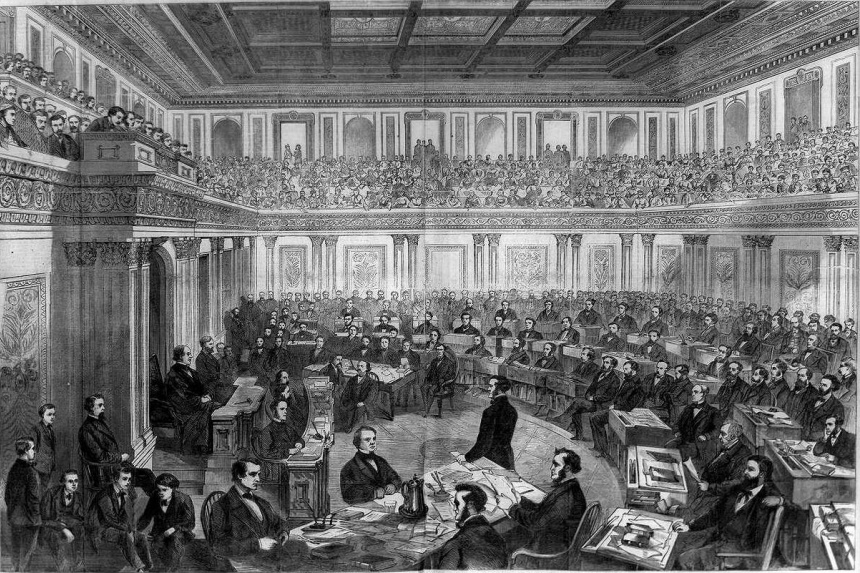

Discussions of the historical contexts for our current impeachment inquiry have tended to focus on the nation’s three prominent prior impeachment trials: Andrew Johnson’s in 1868, Richard Nixon’s in 1974, and Bill Clinton’s in 1998-99. Each of those prior impeachments does indeed offer instructive parallels to our present moment, as well as significant divergences that reflect the time periods, the political and media landscapes, and the historical figures at their center—and can also help us better understand our own evolving, 21st century histories.

Yet there’s another, even more foundational context for impeachment: the U.S. Constitution. The story of its creation includes the striking way impeachment was included and illustrates the radical aspects of this entire document and the government and nation it created.

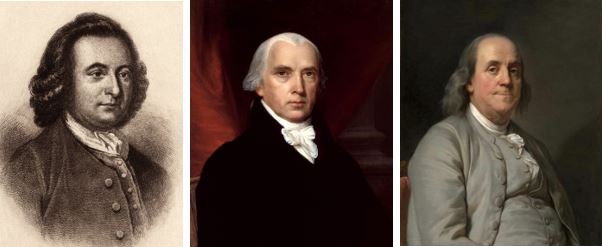

The concept of impeaching the nation’s executive officer was proposed almost immediately in the Constitutional Convention’s opening session. The Convention was convened in Philadelphia on May 25th, 1787, with Virginia Governor Edmund Randolph introducing James Madison’s Virginia Plan as a starting point for deliberations. A week later, on June 2nd, Virginia delegate George Mason introduced the topic of impeachment into the debates, arguing for “some mode of displacing an unfit magistrate.” The delegates voted that same day to include the concept in their draft in progress, using the Virginia Plan’s language that the executive would “be removable on impeachment and conviction of malpractice or neglect of duty.”

Both the concept and the language continued to be debated throughout the convention, however. On July 20th, South Carolina’s Charles Pinckney and Pennsylvania’s Gouverneur Morris made a motion to remove impeachment from the draft. Morris argued that reelection would be a sufficient mechanism for holding the executive accountable, noting that impeachment might “render the Executive dependent on those who are to impeach.” But Benjamin Franklin, the Convention’s elder statesman, disagreed, arguing that the alternative would be assassination, and that instead “it would be the best way therefore to provide in the Constitution for the regular punishment of the Executive where his misconduct should deserve it, and for his honorable acquittal when he should be unjustly accused.”

The Virginia delegates followed up Franklin’s advice with the Convention’s most extensive and specific arguments for including impeachment in the Constitution. Mason asked, “Shall any man be above Justice? Above all shall that man be above it, who can commit the most extensive injustice?” Madison added that, “The limitation of the period of his service was not a sufficient security. He might lose his capacity after his appointment. He might pervert his administration into a scheme of peculation [financial gain] or oppression. He might betray his trust to foreign powers.” And Randolph concurred that “the Executive will have great opportunities of abusing his power.” Their arguments prevailed and impeachment remained in the document.

By early September, the Convention was winding down and the Constitution’s final draft nearly completed, but the precise definition of impeachable offenses remained in dispute. The aptly named Committee on Postponed Matters, established on August 31st, voted to replace “malpractice or neglect of duty” with the more specific charges of “treason and bribery.” But on September 8th Mason argued that those charges alone “will not reach many great and dangerous offenses,” and proposed adding “or maladministration” after bribery. Madison objected that “so vague a term will be equivalent to a tenure during pleasure of the Senate,” and Mason proposed “other high crimes and misdemeanors against the State” as an alternative. That language was added to the draft, with “the State” amended to “the United States” “in order to remove ambiguity.” But in their final revisions for the Constitution’s September 12th draft the Committee on Style and Arrangement (which included Madison among its five members) removed the clause’s final phrase entirely, leaving the definition of “high crimes and misdemeanors” particularly open for continued debate and interpretation.

Those ongoing debates over how to define and apply the Constitution’s list of impeachable offenses have informed every impeachment inquiry, past and present. Yet they shouldn’t elide the strikingly radical nature of impeachment’s simple presence in the Constitution. In the late 18th century, every Constitutional Republic (like every other nation of which the framers would have had any knowledge) was ruled by some sort of monarch, a head of state whose power was perceived to be derived from God. While various mechanisms had been developed to challenge lesser figures in those national governments (the Constitutional Convention debates cited a contemporary such challenge, the May 1787 impeachment proceedings against Warren Hastings, the British Governor-General of India), there were few legal means to remove the monarch him- or herself—doing so, after all, represented a challenge to God. Deposing heads of state was thus entirely outside the normal political process, and almost inevitably meant revolution and war.

The Constitutional Convention delegates fundamentally shifted those narratives, creating a system of government and a political process in which removing the executive was entirely possible and legal. That choice likewise reflects a couple other, equally radical aspects of the U.S. Constitution. For one thing, the Constitution created not just an executive figure, but also an entire government completely separate from organized religion. Indeed, the only reference of any kind to religion in the body of the Constitution is the Article VI clause which establishes that “no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.” Every other contemporary nation featured a state religion, a faith to which every member of the government had to profess at least nominal adherence in order to hold their offices; the U.S. Constitution established precisely the opposite, making any and all religious requirements for office seekers and holders illegal.

Finally, impeachment also reflects the Constitution’s profoundly populist emphasis. I named my new book We the People because that opening phrase is perhaps the Constitution’s most striking choice. This founding document begins not with God, nor with a few elites, nor even with the law, but instead with “We the People of the United States,” an expression of a national community. Of course the delegates’ vision of that community was frustratingly limited, and we have been debating how to define that “we” ever since. But that debate has been framed, literally and figuratively, by a Constitution that first and foremost emphasizes the powers of the people — powers that even extend to the legal ability of elected representatives to remove the nation’s single most powerful figure from office.

Featured image: Andrew Johnson’s impeachment trial (Wikimedia Commons)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now