“The thing about common sense is that it’s often wrong,” Sarah Jaffe writes in her recent book Work Won’t Love You Back. In the book — part labor history, part collection of profiles of workers — Jaffe takes aim at some entrenched American ideas about the daily grind.

Many of us were raised to aspire to turn our passion into a paycheck, but Jaffe writes that the whole notion of work as something we enjoy spending our time doing is rather new. Even if there is joy in the work, she says that this can often blur the line between labor and love in a way that rarely benefits workers.

Tracing the ways we work — and who gets compensated for it — from pre-industrial times to today’s video game designers and striking teachers, Jaffe makes a case for a renewed telling of an old story of labor, and perhaps a revival of an old strategy to solve our collective work woes.

The Saturday Evening Post: I was watching a documentary the other day about Mike Wallace, and there was a clip from his interview with Bette Davis. He is asking her about her various relationships over the years, and she says, “[Work] is the least disappointing relationship you can have.” So I have to assume that you wrote this book to refute Bette Davis.

Sarah Jaffe: I didn’t know that she ever said that! I used to buy a lot of old movie star bios at yard sales, and I read a Bette Davis biography that was annotated by her. It’s a wonderful, weird little document if you can find it.

I think the thing that strikes me about that is that it is a very particular concept of the workplace that has a lot in common with a certain narrative of feminism. Like, you shouldn’t run your life around getting married; you should actually go to school and get a good job. This was very much what I was raised with, growing up in the ’80s and ’90s. That story, of making sure your life is about your work and making your relationships second to that, is interesting, because what I’m writing about is the downside of that having become a story that a lot of people believe.

That raises some questions about our relationships to work; like, if you work really hard and don’t become as famous as Bette Davis — if you become an actor who is doing commercials and some speaking roles and playing the dead body on episodes of C.S.I. — you probably have a different relationship to the work than one of the most famous women in the world did. And even her work did not treat her great at times.

SEP: Who would you say is the working class in America?

Jaffe: That is the question, right? I argue in the book that the working class is not a stable entity, but that it’s actually formed through a process that various scholars have called “class composition,” which is what happens as the workplace changes over time. In the book, I’m writing about the ways that the U.S. has shifted away from industrial labor, with factory closures, and toward those things that fill in the gaps — retail work, healthcare, different kinds of work. That changes the work experience, but it also changes who is in the workplace. So the workplace looks different now than it did in 1970 than it did in 1940. So the working class looks different now than it did at those times.

The book is about this process of class composition. I’m collecting stories of some of the most common kinds of work these days, noting that one of the things they have in common even though they’re distinct kinds of work — like paid domestic work and video game designers — is that their bosses are telling these workers that “they’re part of a family.”

SEP: Do you think peoples’ understanding of the working class has changed along with these big workplace changes?

Jaffe: It depends. We still get a picture of the working class that is like my buddy Chuckie Denison, who I met when I was reporting on the closing of the plant at Lordstown. He is a white guy from the Midwest who works in a factory and has spent his entire adult life working at GM. People still kind of think that the working class looks like that, even though it actually looks like Somali immigrant workers in an Amazon warehouse in Minneapolis and Black workers at a poultry plant in Alabama and immigrant women doing home healthcare. I think people who work have a pretty good idea of where they fall, but when we talk about “the working class” as an entity it ends up defaulting somehow to a white man in a factory.

SEP: One of the big ideas that you put forth in this book is “labor of love” and how we’re in this “age of labor of love.” Can you explain that, and how that manifests in labor?

Jaffe: In an industrial job, you don’t have to smile at the car that goes past you on the assembly line. The difference between that and working in retail with customers is that you have to perform what sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild called “emotional labor,” which is the process of moderating your own feelings in order to make somebody else feel a certain way. That is a difference experience in the workplace, and it’s a much more common experience in the workplace now than it used to be.

And alongside that, you see this idea of the “dream job,” this great, exciting job — like Bette Davis. People might aspire to be Bette Davis, or a novelist. Some of the folks I talk to in the book are video game programmers. Those kinds of jobs, that are seen as cool and desirable because they’re supposedly fun, that’s another big part of the workplace. Between those two things, we end up with a different story about work, that we go to work because it’s fulfilling, pleasurable, or because we care about other people or the community — we’re talking about workers like teachers or nurses — and people are expected to be self-sacrificing for their work. So this story takes a lot of forms, but it is a much more dominant narrative about the workplace now than it was, say, when I was a little kid. I trace it in the book from basically two places: one is the story of women’s unpaid work in the home — which everybody is grappling with once again because so many people are being forced to spend all of their time in the home and work from home now — and the way that is expected to be done out of love and not for money.

In the second half of the book I look at that story of creative work, talking about artists and the long-standing expectation of art as “not really work.” The “starving artist” and all of these clichés about people who are special and will create out of their unique genius. Bette Davis was a brilliant, amazing actor — I’m such a fan — and we think of that as, like, a gift that she had. But that also justifies people in those fields not getting paid well or having good working conditions because they’re supposed to be so talented and so devoted to this work that they would do it, even for free.

SEP: Another idea you bring up is the “gamification” of work. Is this just a Silicon Valley thing?

Jaffe: The interesting thing about gamification is that it starts with the programmers and the fun, cool Silicon Valley workplace where there are skateboards and ping-pong tables, but then it turns into something like Amazon turning picking items in a warehouse into a game. If you pick more items faster, then you win the game. There was one about dragon hunting, I think? Uber is another one that has gamified picking up rides. These games are supposed to make the work more fun, but they’re also designed to make you work harder and faster. My friend Molly Crabapple actually said years ago at a panel at South by Southwest, “And the prize is what used to be called your salary.” But you’re still picking up items and putting them in a box so that Jeff Bezos can be one of the world’s richest men.

SEP: You’ve been reporting on labor for a while. Do you think we’re experiencing a resurgence in the labor movement?

Jaffe: We are, in many ways, seeing a revival in certain sectors. Karen Lewis was the president of the Chicago Teachers Union for several years, during the time when they revived militant struggle for teachers, and she just recently passed away. She was an incredible woman, and she and the people she worked alongside in that union did a lot to change the perception of teachers’ unions. They’re getting blamed for a lot now, but before 2012, teachers’ unions were getting blamed for everything. Karen and the Chicago teachers changed that narrative. They said, actually we’re struggling for better schools because we love our students. We’ve seen that shift really pick up, with the red state strike wave a couple of years ago.

There is definitely a renewed militancy, renewed activism, and a renewed use of things like the strike. In other places, it continues to be downhill. One of the interesting things that we’re seeing, that I talk about in this book, is the revolt of the labors of love. Art museum workers and non-profit sector workers have been unionizing. Before, non-profit workers would be vulnerable to the argument that they’re doing it for the cause, so it doesn’t matter what their working conditions are. If you don’t work long hours and burn yourself out then you are insufficiently devoted to the cause. Journalism — our industry — has seen a lot of union drives in recent years.

I would feel better calling it a revitalization if the union density numbers were higher than 12 percent. That said, I think there is a lot of cause for interest in the various sectors that I’ve written about in this book.

SEP: As far as the gender divisions of labor — the unpaid labor of housework and child-rearing, this is something people have been talking about and studying for a while now. What do you think people are still misunderstanding about this?

Jaffe: This is involved in the argument to reopen schools, because there’s this argument of “Moms are stressed and we need to reopen schools because moms are stressed!” But a lot of teachers are moms too. Seventy-six percent of teachers in this country are women. But yes, moms are stressed because we haven’t done anything in the last several decades to help them. Anyone who is taking care of children is exhausted right now, and for good reason. We’re the only country in the industrialized world that doesn’t have paid family leave, and the last time we got any policy on that front was in the 1990s under Bill Clinton, when we got the right to not get fired if we take time off to have a baby.

As a matter of public policy, we don’t respect the work that is done in the home. It gets sort of made into this debate between men and women in the home, or women and women, like right now when teachers are supposedly the problem. Or it’s between women and the women they hire to do the work. But really, this is something we have to solve with public policy answers, not something we can solve individually. I think this is true for basically everything I’m writing about in the book, but we uniquely resist the idea that what goes on in the home is a matter for public debate.

The reality is that people are stressed because raising a child is a burden that is entirely placed on an individual or an individual family, and there is almost no help for that other than the existence of public schools. There is very little help with any childcare. There’s finally talk about expanding the Child Tax Credit and making it fully refundable. If we had nationally mandated paid sick time and family leave. Federally-supported daycare almost happened a couple of times in history, and in fact it did happen during World War II. So we’re in a situation where we can’t fathom solutions to the problem other than reopening schools before we’ve gotten the virus under control. But it’s really hard to understand that what’s done in the home is still work.

SEP: Who needs to be reading your book the most?

Jaffe: I was really pleased today when someone tweeted about buying the book for her grandma. A friend of mine who works for the Autonomy think tank wrote a piece once about how the revolutionary subject is your grandma. So, right now I want grandmas to read my book.

I’m starting to think about my book as a consciousness-raising project. Like in the ’60s, it was a process of women getting together and talking about their personal conditions together, realizing that they all had versions of the same problems. That meant those problems were political.

All of these things that seem like individual problems that we struggle with on our own are actually things that we have to solve together.

I think there is this sense in a lot of different places that the promises we were made about what work would do are no longer being fulfilled if indeed they ever were, so I wrote the book to capture that, to say, “You’re not crazy. This is true, and here are the numbers and the history and the story of how we got here. Here are a lot of other people who feel the way you do, and here are the ways in which they’ve tried to change it.”

SEP: What would you do with your time if you didn’t have to work?

Jaffe: Right now I need to clean my house.

SEP: That’s unpaid labor!

Jaffe: I just want to go to the park with, like, 20 of my closest friends, and talk for five hours, and cuddle. I would love to be able to see what kind of creativity my brain would be capable of if I didn’t have to do things for work. What would I write if I could make up stories all day long. There are people who get paid to write fiction, but once you get paid to write it you are subject to the demands of publishers and all of these other things. I think there is so much creativity that people have and would love to play with if we had the time to do it. But it’s been narrowed down into a job for the handful of people who can become Bette Davis. What else could we do if we all got to spend time making things and having fun?

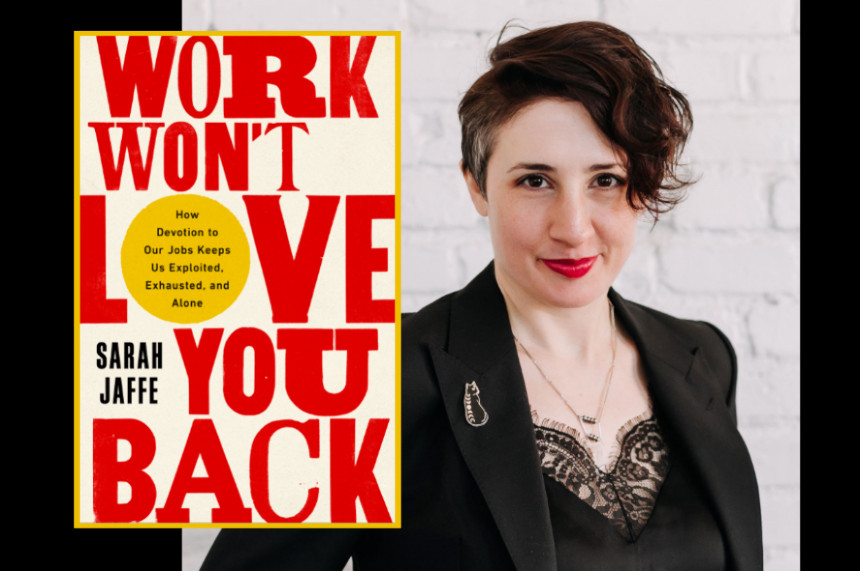

Featured image: Photo by Amanda Jaffe, Work Won’t Love You Back cover, 2021 Hachette Book Group

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now