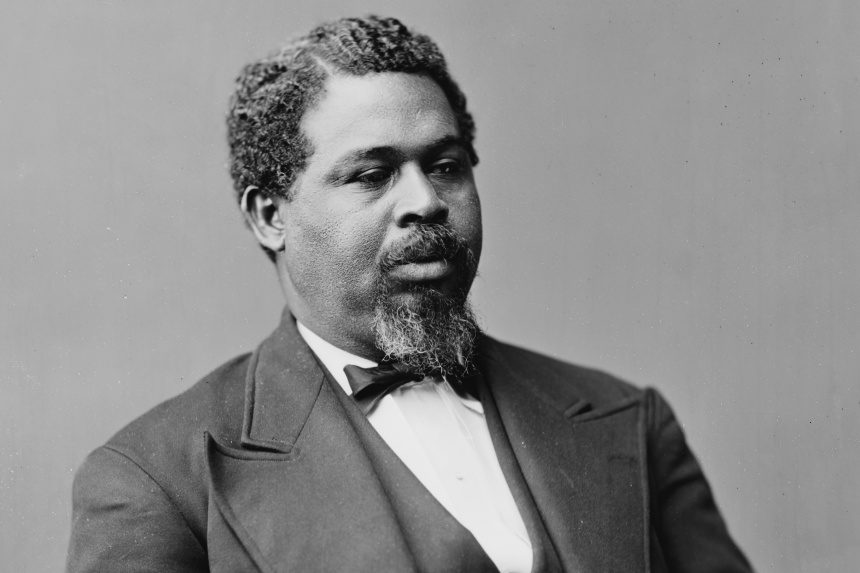

America likes to think of itself as the type of country where anyone can become anything, and that the person born at the lowest point in society can ascend to a much higher place. The life of Robert Smalls was like that. Born into slavery in South Carolina, Smalls would eventually serve on behalf of the state in the U.S. House of Representatives. The path that took him there runs through the amazing story of how he commandeered a Confederate ship and became both a pilot and an unofficial captain for the Union during the Civil War. With later chapters spent crusading for education and his own vindication in a system that didn’t properly recognize his contributions, the tale of Robert Smalls turned out to be larger than life.

Born in 1839 to Lydia Polite, both Robert Smalls and his mother were slaves of a man named Henry McKee. When Smalls was 12, his mother persuaded McKee to send him to work in Charleston, with his wages going back to McKee. Smalls eventually started working at the docks, where he learned a variety of skills and how to do several jobs on a ship. Though social norms stopped short of allowing him to have a helmsman title, he knew how to handle the wheel and pilot a boat by the time he was 17. He married young and planned to try to earn money to buy his family out of slavery.

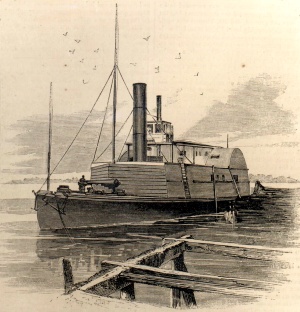

When the Civil War began, Smalls found himself in the service of the Confederacy. He was placed aboard the CSS Planter; the Planter served as a transport while also laying mines. As a pilot, Smalls got used to navigating in his home state, Georgia, Florida, and along the southeast coast. A Union blockade was positioned seven miles out from Charleston harbor, and that gave Smalls the impetus to form a dangerous notion. In 1862, he began to recruit fellow slaves on the ship for an escape plan.

On May 12, 1862, the Planter collected cargo of 200 pounds of ammunition and four large guns. The ship docked for the night, and, as was typical, the white officers departed to sleep on land while the crew remained on the boat. Smalls requested if the families of he and his fellow crew could visit, and the captain gave permission so long as they were gone by curfew. When the families arrived, Smalls and company revealed their escape plan. Three of the crew faked returning the family members, but doubled-back to a pick-up location. Smalls dressed in the captain’s garb and a straw hat of the type the captain favored and sailed to the rendezvous. Collecting their crewmates and the families, they set out, sailing past the five forts on the harbor and right toward the Union blockade. The crew pulled down the Confederate flag and ran up a white sheet that Smalls’s wife had brought with her. When Union officers boarded the boat, Smalls presented the ship and guns and asked for a Union flag to put on the mast.

Word of Smalls’s action got around. Letters flew among Union Naval leadership, particularly praising the Smalls plan and the intellect of the man behind it. Smalls had also taken a Confederate codebook and detailed intelligence regarding troop dispositions and armament. Acting on the information from Smalls, the Union captured the nearby Coles Island installation a week later and held it for the remainder of the war. As the story circulated in the North, Smalls was featured in a number of newspapers. The Navy paid Smalls and his crew a bounty for delivering the ship and guns. Union Admiral Samuel DuPont employed him to identify the location of mines that the Planter had laid near Charleston; he also wrote of Smalls in a communique to the Secretary of the Navy: “[Smalls] is superior to any who have come into our lines — intelligent as many of them have been.”

Soon after, Smalls was instrumental in the effort to convince President Abraham Lincoln to allow Black soldiers into the Union forces. Their meeting was recounted in the book Yearning to Breathe Free: Robert Smalls of South Carolina and His Families by Andrew Billingsley. Smalls met with members of the cabinet before speaking with Lincoln. According to Billingsley, Lincoln was “enthralled” by how Smalls told the story of the Planter, and developed “appreciation and admiration” for the man. Lincoln soon issued the order to raise 5000 African-America troops; Smalls himself delivered the order from the president to General Rufus Saxton.

Throughout the course of the war, Smalls served on a number of ships, working as pilot on several. He made his way back to the refitted Planter. At one point, the ship drew heavy fire and the captain hid. Smalls took command and evaded capture. General Quincy Adams Gilmore promoted Smalls to the rank of captain and made him acting captain of the Planter. Although this was “known,” technicalities made it so that Smalls’s promotion was viewed by many as unofficial. He captained the Planter throughout the war, and he and the ship were present when the U.S. flag was raised again over Fort Sumter at the war’s end. Years later, Smalls had trouble getting his Navy pension because his promotion was deemed unofficial. A special act of Congress in 1897 eventually awarded him a pension equal to that of a captain’s rank. In 1900, another Congressional act gave him additional compensation for the original award he received on the Planter, with Congress noting that the first payout should have been valued higher.

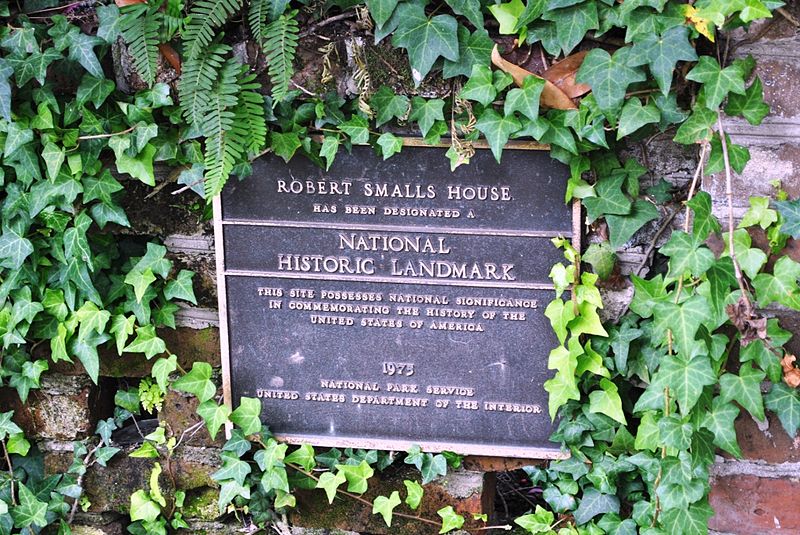

Smalls used his renown and money to advance the Black community in South Carolina. He opened a freedman’s store with partners, he owned and published a Black-owned newspaper (the Beaufort Southern Standard), and he co-founded a majority Black-owned horse-powered railway. Smalls also lent his voice to education issues and helped pave the way for South Carolina to be the first state that offered compulsory, but free, schooling. He became active in politics, and was elected to the state House in 1868; after serving two years, he was elected to the state Senate and served until 1875. Smalls was eventually elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, serving a total of eight years across three terms for two districts.

Suffering from diabetes and malaria, Smalls died at age 75 in 1915. A variety of schools and military locations in South Carolina have borne his name. In 2004, the U.S. Navy named a logistics support ship Major General Robert Smalls; it’s the first U.S. Naval vessel to be named after an African-American. A film about the exploits of Smalls on the Planter is currently in development. A monument for Smalls at his gravesite is inscribed with a quote taken from 1895; in front of the South Carolina legislature, he said, “My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.” Smalls took his chance, and he proved to be more than equal to the task.

Featured image: Robert Smalls (Photo by Mathew Brady and Levin Corbin Handy. Wikimedia Commons via Library of Congress; public domain)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Why is there no mention of him being a state representative and senator and U.S. congressman, all as a Republican anywhere in the story? Also not mentioned is, later in his term as a U.S. Representative, how Democrat “Red Shirts” intimidated his constituents from voting causing him to barely lose his office.

Fascinating story of a great American I was never taught about in school, which is a shame. Hopefully that will change as history books/education is updated to include him. The film in development (per link) sounds really good, and one I’d like to see.

I like what a smooth operator Robert Smalls was. He accomplished so much by working within the system to manipulate it for the common good of everyone; not just Blacks. Not many historical figures can touch this man, with Ben Franklin being one of the few. Obviously Mr. Smalls knew how to use charm along with logical reasoning to get what he wanted, and had to be even more brilliant because he was Black.

Our nation has a complete dearth of men of this caliber, which only grows more tragically obvious by the day. “Leaders” out to exterminate our people. Economic Auschwitz. Hitler would be so proud and approving. Mitch McConnell would be his favorite. Straight out of ‘Rosemary’s Baby’.