Long after our mothers have gone, we have the memories. Often evoked by Mother’s Day.

I remember sitting in the banker’s office while my parents applied for a mortgage.

My family was not wealthy, but we’d never had any problem when applying for charge accounts (these were the days before credit cards) or filling out forms when my father’s work forced us to move and rent a new home. We were living on Cape Cod and had found a home we wished to purchase and make it, if not a forever home, a home for the foreseeable future.

The banker sat behind a big mahogany desk with a polished glass top. My father had taken a seat to his left, ready to sign whatever needed to be signed. I was on the corner and my mother was seated directly opposite the banker. The banker ran through the financial questions on the form which I look back upon today as a financial autopsy.

When he finally stopped, my father had sagged a bit in his chair, as had I. I could feel my tail bone against the hard surface.

Not my mother.

She had drawn herself up in the armchair, shoulders squared as she said, “We may not be rich, but we’re nice.”

Some 27 years later that same spirit showed in a Duke University hospital room. It was the spring of 1983, and she was soon to go from the hospital to a nursing home.

But that spring day when I went for my daily visit after work, I took a copy of the just published Who’s Who of American Women, in which I was listed for the first time. It was a large book and so heavy we’d propped it on the pull-to tray alongside her bed. As it rested inches above her chest she turned to the listings for Lauder. There were only two then — Estee Lauder and me.

She read the entries — absorbed mine is more like it — then said: “She may have more money, but you have more space.”

As the little boy said in a TV commercial years ago, “Mothers are like that. Yeah, they are.”

One of my favorite memories: We were still living on Cape Cod but felt it important to get closer to New York for my father’s business consulting job, which required extensive travel with only occasional weekends home. So we looked at possibilities. One day my mother and I went to Old Saybrook, Connecticut, halfway between New Haven and New London. We went to the train station for mother to check out trains and schedules. I waited in the car with our cocker spaniel Taffy.

When my mother returned to the car she was extolling the man behind the barred window in the station; in fact, she couldn’t say enough good things about him. For he was a man who held a position that was not high on the personnel chart, but who took great pride — exuded it — in the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad he served.

As mother told it, he not only handed her a schedule, he fairly gushed as he gave her the information she’d requested. He was still filling her in on the schedule when the express train approached. He said, “Here’s one of our trains now.”

It roared through, vibrating everything within yards with the sheer force of its forward motion. And when mother turned back to him, she said with a sly smile reminiscent of the Mona Lisa, “But it’s sort of hard to get on, isn’t it?”

Born on the eve of a new century — December 28, 1899 — she liked to say she wanted to see the next one in. She did not make it, passing just before Christmas in 1983. But she saw a lot of history. And was part of it, in a small way.

Among the many changes of her time was the role of women and the opportunities that were open to them. She, unfortunately, was not a major beneficiary as she assumed the traditional role of women at the time. When she went to college she wanted to be a lawyer, but women were not allowed to attend law school.

So she settled for library school (nothing against books) and became a librarian in Detroit, Michigan. It was while she was working there that my parents married. On March 1, 1926, I was born. As her concerns became motherly, she developed a strong interest in finding ways to make my child’s play if not formally educational, not idle.

I remember my mother talking about how there was much around the house that could offer valuable playtime for a child. One example was a handmade version of the toy where you dropped various shaped pieces into matching openings. Her homemade version was a Quaker oatmeal package, that familiar silo-like cylinder that had, at that time at least, a metal bottom. She would cut a circular hole in the top and then a child could drop in circular pieces, such as round poker chips.

She began sharing her efforts with the neighbors, and before you knew it she was putting on local events to share the ideas with others. Somewhere in the family albums is a picture of me in her arms standing next to the governor of Michigan that year (circa 1928) at the opening of one of her events on a grander scale.

Soon department stores wanted to tap her findings and services to bring a new dimension to their sales of toys for children. She made trips to New York and Philadelphia.

When she was in Philadelphia, Daddy and I went to visit. At the time, the store had Mother Goose on its payroll, who offered to look after me while Mother and Daddy went to dinner.

I was probably three or four and all I remember is Mother Goose’s hat — one of those inverted traffic cones perhaps three feet high. But, Mother Goose was one of my baby-sitters!

And wonderful toys would appear in our living room, as Mother worked with top manufacturers. At a time when dolls were pretty much a stiff form with a dress, I particularly remember the baby doll that had rubber textured skin that made it possible to give the doll a bath. It came with a small trunk, a light brown color with the labels of great cities like those found on the trunks of trans-Atlantic travelers.

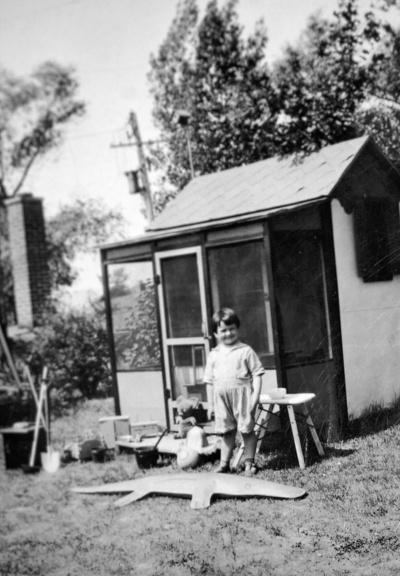

My favorite, though, was the rubber alligator. It was five to six feet long, as I remember it, a bright lemon yellow and lime green that I had for the near idyllic summers at my maternal grandparents’ cottage at Zukey Lake, near their home in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where my mother grew up. I would sit astride the alligator at lake’s edge or lay it out on the lawn before the playhouse Grandpa Mann had built me — an embarrassment of playtime riches.

Alas, she was not a good businesswoman.

While working in New York, where she was creating toys for children that would come to be called educational toys, a salesman for a toy company came by one day. He saw what she was doing and said his company would be interested in making and selling them.

He made a formal proposal. I think it included a percentage of what she would receive on each toy.

She agreed to the terms but did not get it in writing.

He took the ideas to his company as his own. They would become the foundation of one of the nation’s largest toy companies. She never received a penny.

Had she gotten his offer in writing, we could have been rich and nice.

Featured image: Courtesy Val Lauder

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Very interesting story about your mother, Val. She was a very bright woman in creating new types of toys for children that were both fun and educational. The salesman in New York for that toy company that presented your mother’s ideas as his own, was a real louse.

Who knows how much money that company made and could still be to this day, despite all the corporate buyouts and acquisitions in the decades since. If it’s any consolation, its not uncommon for creative people to be not so hot when it comes to business, and vice versa. Just remember in the big picture, all the children she’s enriched and will continue to.