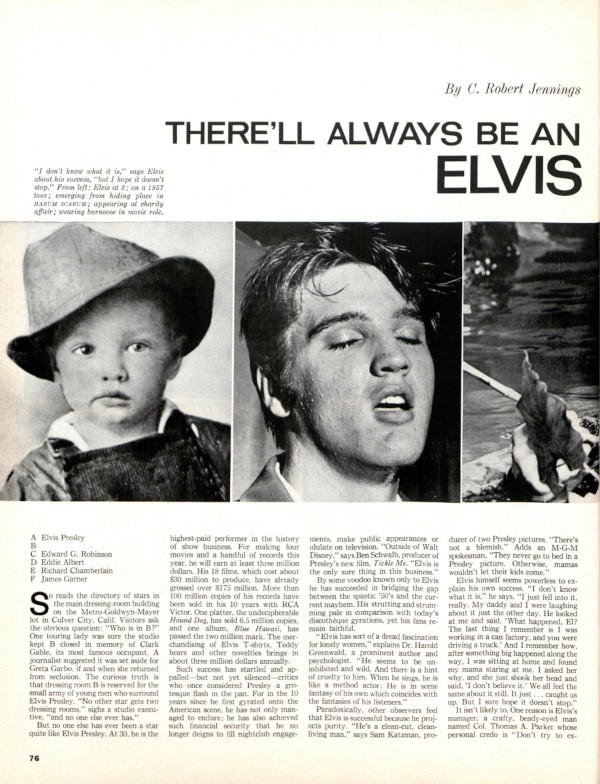

—From “There’ll Always Be an Elvis,” from the September 11, 1965, issue of The Saturday Evening Post

No one has ever been a star quite like Elvis Presley. At 30, he is the highest-paid performer in the history of show business. For making four movies and a handful of records this year, he will earn at least $3 million. His 18 films, which cost about $30 million to produce, have already grossed over $175 million. More than 100 million copies of his records have been sold in his 10 years with RCA Victor. The merchandising of Elvis T-shirts, teddy bears, and other novelties brings in about $3 million annually.

Despite his wealth, Elvis today leads a remarkably undramatic existence. He lives behind electrically operated gates in a villa in Bel Air. He does not touch liquor, and smokes only an occasional cigar. He attempts to keep in shape by dieting on yogurt and coffee, but now and then he succumbs to gastronomical temptations.

A few years ago his favorite recreation was the dodgem cars at nearby amusement parks, but he has since outgrown that stage. Asked what he did, say, last weekend, he will reply: “Oh, I took the Rolls out for a drive, but the freeways were so crowded that I came back home and watched TV.”

When he’s not watching television, Elvis relaxes by indulging in an almost continual round of playful pummeling with the eight young male assistants who live with him and who are known colloquially as the Memphis Mafia. Elvis handles his court with all the aplomb of a Renaissance prince. “I am the boss,” he says. “I have to be. I have no need for bodyguards, but I have very specific uses for a highly trained CPA, another man to handle travel arrangements and make reservations, a wardrobe man, a confidential aide, and a man to handle security in crowds. This is my corporation.”

Elvis has shown affection for Anne and Connie and Tuesday and Jocelyn and Joan and Jackie and Anita and Mary Ann, many of them co-stars in his movies. In G.I. Blues, his love scenes with Juliet Prowse went far beyond the helpless director’s cries of “cut.” Finally director Norman Taurog called him aside and said, “You don’t have to put your heart and soul into it.” Replied Elvis: “How can you help but put your heart and soul into this?”

His dedication to these love scenes seems to be appreciated. “He’s really one of the most sincere people in the most insincere town on earth,” says Juliet Prowse.

Diplomatically, Elvis himself refuses to comment on the passing parade of cute young things who come to visit him. “So far,” he says, “there just doesn’t seem to be enough time in my life for getting serious with women. Things might be different if I weren’t so doggone tied up with cutting records and making movies. But the girl I marry will have to like the way I live — I’d sooner go out and get a hamburger than go to a nightclub. And she’ll have to like Memphis.”

Elvis insists that “Memphis will always be my real home.” Yet he is in fact a Mississippian, born dirt-poor in a two-room shack in Tupelo (pop. 17,221), the surviving member of twin boys whom Gladys Presley named Jessie Garon and Elvis Aron. “My mama never let me out of her sight,” he recalls. “I couldn’t go down to the creek with the other kids. Sometimes, when I was little, I used to run off. Mama would whip me, and I thought she didn’t love me.”

As a boy Elvis never studied music, but he had a cheap radio which he would listen to for hours at a time. “I liked to hear Grand Ol’ Opry,” he recalls, “and I loved the records of cowboy singers like Roy Acuff and Hank Snow and especially Gene Austin. I sang some with my folks in the Assembly of God church choir. It was a small church, so you couldn’t sing too loud.

“Getting a guitar was mama’s idea. I beat on it a year or two and never did learn much about it. I still know only a few major chords.”

When Elvis was 13, his family moved from Tupelo to a public-housing project in Memphis. There he attended Humes High School. After his graduation in 1953, he found employment on the assembly line of a precision-tool company, at a furniture factory that made plastic tables, and as a driver for the Crown Electric Co.

In the summer of 1954, Elvis had a multi-million-dollar inspiration or, as he explains it, “just a urgin’.” He went to the Sun Record Co., plunked down some money, and twanged out a tune on his guitar. “It sounded like somebody beating on a bucket lid.” Elvis grins — exposing his sparkling studio-capped teeth. “The engineer told me I had an unusual voice — isn’t that something? He said he might call me up sometime.”

Months went by without word from the engineer, and Elvis kept driving his truck for $35 a week. At night he attended a trade school and studied to be an electrician. To pay the tuition, he ushered in a movie house. Whenever he could find time, he went to all-night “singin’s.” “Some of those spirituals had big, heavy rhythm beats like a rock-’n’-roll song,” Elvis remembers. “That music didn’t hurt anybody, and it sure made you feel good.”

In the spring of 1955, Elvis received a telephone call from Sam Phillips at Sun Records. Could Elvis come down to record a ballad called “Without You”? “I tried it,” Elvis recalls, “but I just couldn’t do it the way they wanted me to. Then Mr. Phillips took a coffee break, and I started fooling around singing a song with a rock-’n’-roll beat. They liked it, and we recorded ‘That’s All Right, Mama.’ Then we made ‘I Don’t Care if the Sun Don’t Shine’ backed up by ‘Blue Moon of Kentucky.’”

When the songs were first played on radio station WHBQ, Elvis hid in a movie theater. “I thought people’d laugh at me,” he explains. “Some did, and some are still laughing, I guess.” But that week, 7,000 copies of the record were sold in Memphis alone. Elvis was on his way.

Six months later Col. Thomas A. Parker agreed to handle “Mr. Presley” and booked him on tours with such established personalities as Hank Snow and Andy Griffith. By the fall of 1955 the reverberations had reached Manhattan. Persuaded by Colonel Parker, RCA bought his contract for $35,000. Additionally, Elvis received a $5,000 “bonus for signing.” It was more money than he had ever seen in his life.

In January 1956, RCA Victor released its first Presley record. Called “Heartbreak Hotel,” it was a blood-stirring dirge of love and loneliness that burned up the jukeboxes and eventually sold two million copies. Six months later Elvis helped Steve Allen beat Ed Sullivan in the Sunday-at-eight television battle. Sullivan affected disdain for Elvis (“I’ll not have him at any price — he’s not my cup of tea”) but soon reversed himself and signed the young singer for $50,000 — more than Sullivan had ever paid anybody. Hal Wallis brought Elvis to Hollywood for a screen test and signed him to a seven-year contract which has since been extended.

Not everyone swooned, and sizable shock waves of outrage swept the country. Leading newspapers denounced him as “lewd and obscene.” Ministers mounted whole sermons against him. Other detractors spread stories that his pernicious noise was actually produced, like the voice of the cricket, by some violent stridulation of the legs.

The criticisms stung both Elvis and his family. “I didn’t do no dirty body movements,” he announced self-righteously. “When I sing, I just start jumping. If I stand still, I’m dead.” Elvis didn’t stand still, and the sound blared out relentlessly from a score of phenomenal platters.

In the spring of 1958 the Grand Panjandrum of Jump became just plain Private Presley, Army serial number 533 107 61. For the next two years, he passed up a Special Services job entertaining the troops and accepted a more mundane assignment as a jeep driver at the U.S. Army base in Friedberg. “I didn’t want to take any special privileges or favors or use influence.”

During his absence Elvis had earned $1.3 million from record royalties; upon his discharge RCA announced that it had received a whopping 1,275,000 advance orders for “Stuck on You,” his first post-Army disc.

He returned to Hollywood and began to lead a relatively quiet personal life. His dress became less jazzy; his cars were fewer in number and more conservative. He collected books on medicine (“I always wanted to be a doctor”) and classical records by Caruso and Kirsten Flagstad. He seldom went out. Gradually the glittering people have stopped inviting him places. He could not be happier.

“I never expected to be anybody important,” he explains. “I figure if these things bother me too much, though, I could always go back to driving a truck.”

This article is featured in the July/August 2021 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Courtesy doctormacro.com

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now