In 1946, a nationwide competition was held among the leading illustrators in America. The illustrators submitted their favorite works for an exhibition, and their entries were judged by the editors of the top magazines. First place went to an unschooled immigrant named John Gannam, who beat Norman Rockwell for the prize.

Who was this John Gannam, and how in the world did he manage to best Rockwell?

Gannam was born Fouzi Hanna Boughanam in 1905, in the small village of Machghara, located in the Beqaa Valley of Lebanon. His parents fled Lebanon to avoid wars and civil unrest and brought their son to the United States on a steam ship. Once they arrived, the father found work as a street peddler and changed the family name to “Gannon.”

Young Fouzi Gannon started school in the U.S., but he was forced to drop out at age 14 and find work after his father died. He struggled through jobs as a newspaper boy and a bellhop before finding work as a messenger boy at the Crescent Engraving Company. There he saw artists preparing pictures for mail order catalogs and discovered his true calling in life.

Fouzi had no formal art training, but he carefully observed the company artists as they worked. By following their example, he taught himself to draw at home at night. He gradually developed a portfolio of samples, and in 1926 when he turned 18, he took his samples and went out looking for a job as a real artist. He changed his first name from Fouzi to John, and later changed the family name Gannon to Gannam. The newly Americanized John Gannam landed a few random assignments before finding steady work at a commercial art studio in Detroit, where he illustrated ads. Despite his lack of training he quickly impressed the boss with his hard work and dedication. His reputation spread, and in 1930 he was hired away by a better studio in New York.

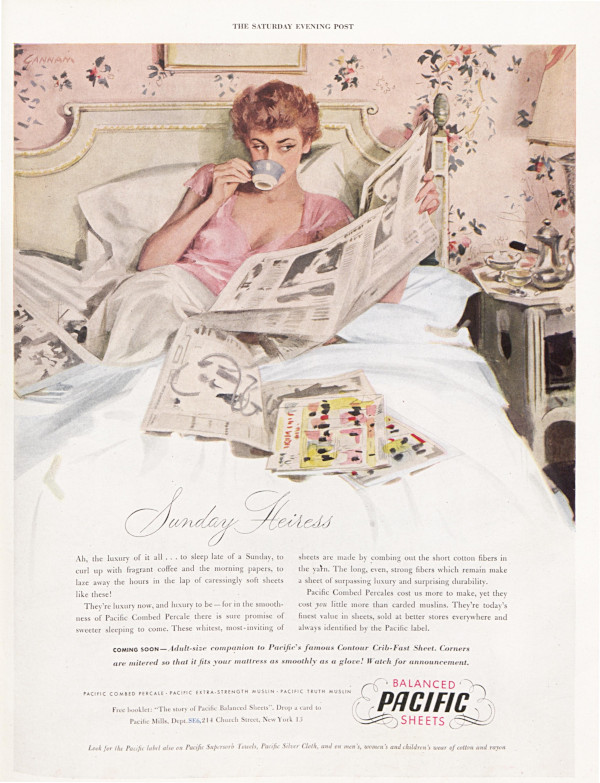

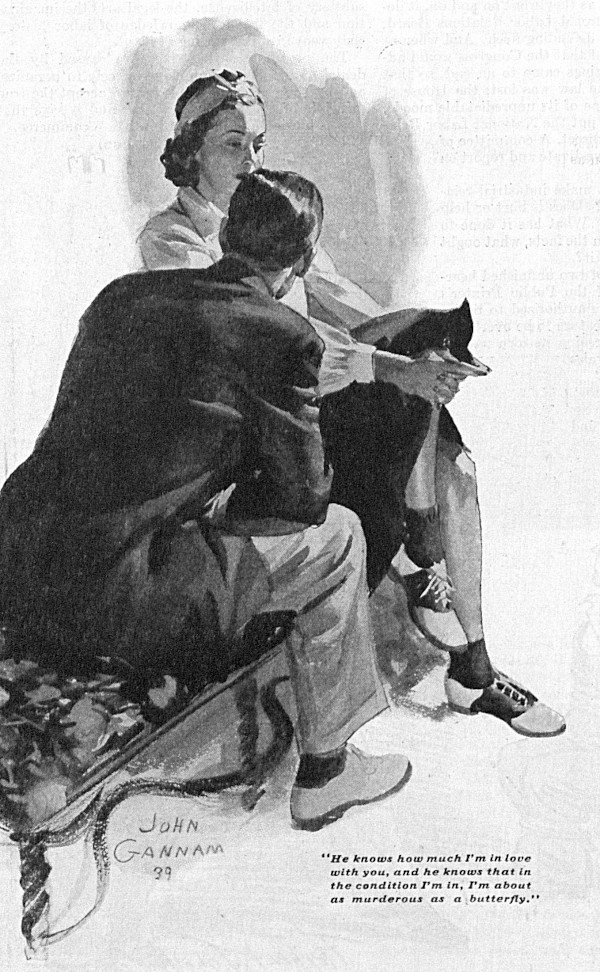

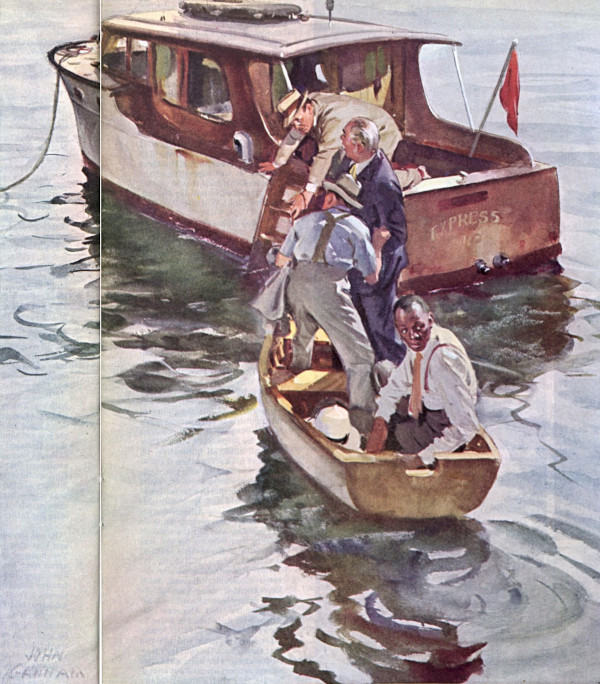

As Gannam continued to improve, he developed a talent for watercolors. Other illustrators liked to work in oil paint or ink or pencil, but Gannam loved the special qualities of watercolor — a challenging, temperamental medium. His watercolor paintings had such a high-class, artistic feeling, they were sometimes compared to the watercolors of fine artists such as John Singer Sargent or Winslow Homer. Gannam exhibited his watercolors in fine art shows and became an associate of the National Academy of Design. He was a member of the American Artists’ Professional League, the American Watercolor Society, and was appointed to the faculty and board of directors of the Danbury Academy of Arts.

His commercial advertising clients loved Gannam’s “fine art” feeling because his artwork made their products look “classy.” Notice the beautiful mood he created in this advertisement for Pacific Mills sheets:

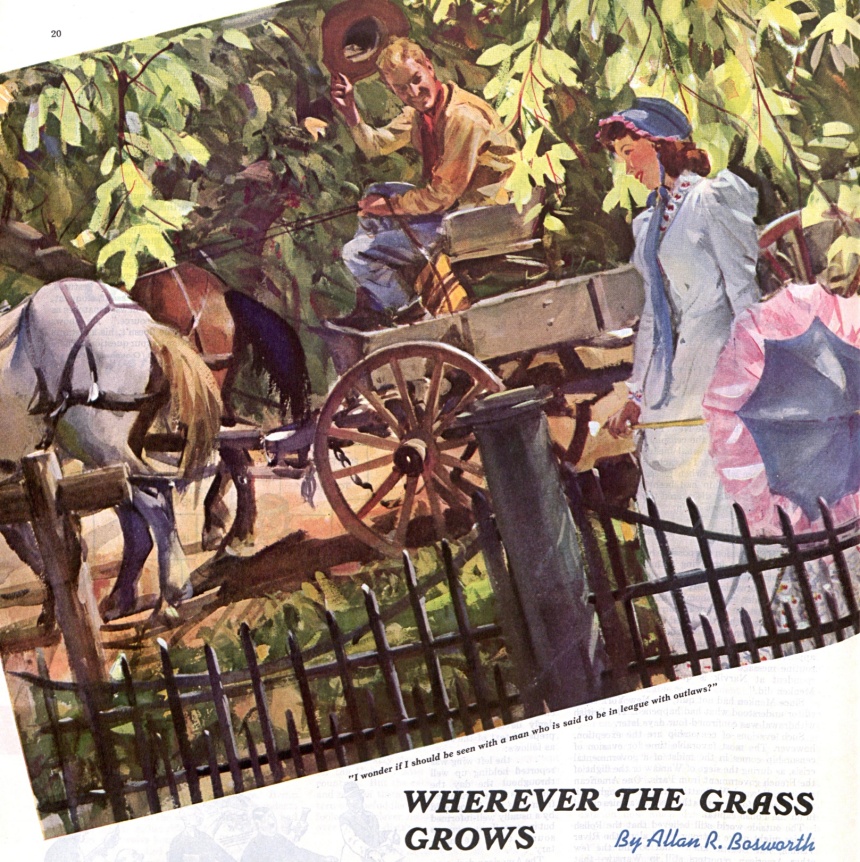

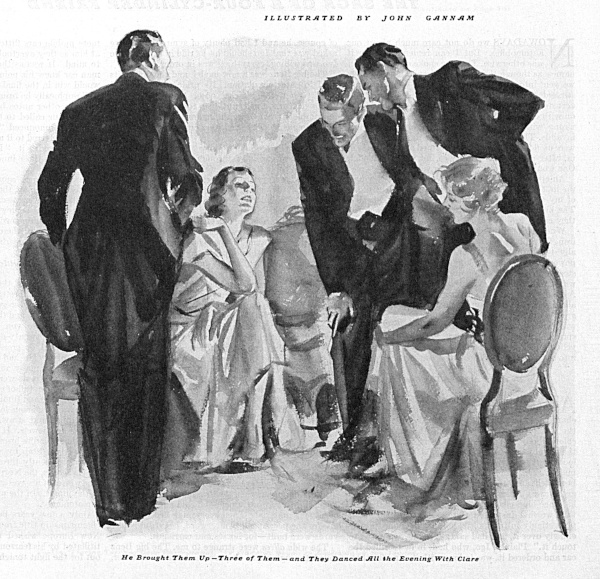

Gannam’s first job illustrating fiction for magazines was for The Woman’s Home Companion. Other magazines were impressed by his talent and soon came calling. He worked for Cosmopolitan, Good Housekeeping, and Collier’s. Then in 1933 he received his first assignment from The Saturday Evening Post, beginning a long and fruitful relationship.

His competition learned at art schools, or by apprenticing for an established artist, or finding a mentor or coach. Gannam had none of these, but he made up for it with hard work. He developed a national reputation as a diligent perfectionist who practically lived in his studio.

In his book, Masters of American Illustration, art historian Fred Taraba wrote, “the consummate hard worker, Gannam needed an environment free of interruptions….In hopes of not being disturbed, Gannam would frequently remain in his studio for as long as two weeks at a time.” He was something of an art hermit, and this became a source of jokes among his peers. When Gannam was inducted into the Illustrators’ Hall of Fame, one of the speakers remarked, “some said he seldom changed his socks. If this is true maybe the rest of us change ours too often.” They described the 5’4” Gannam as “a funny looking, baldheaded little guy,” yet they couldn’t help but revere his beautiful watercolors.

Illustrator Arthur William Brown reported,

John Gannam was totally devoted to his work, spending all his waking hours either working, or thinking about the next assignment.…ask if he had any hobbies, he responded: “my work takes me day and night to do, and it’s the most important and exciting thing in my life, so it must be my hobby.”

Even when he took a rare vacation to go fishing, he came back with more watercolors than fish.

Of course, perfectionism isn’t always a good thing in an illustrator. At Gannam’s Society of Illustrators tribute, artist and friend Charles Hawes said,

He was…an editor’s and art director’s nightmare, for he was never quite satisfied with his work. Deadlines always came second to perfection. A story set for a winter issue might be ready for a summer one. This never ruffled him and nobody ever saw anything less than what he considered his best.

Gannam’s heavy work schedule was all focused on quality, not quantity. He could become preoccupied with painting light and color, experimenting with different ways to capture reflections of streetlights on wet pavement or rushing water over rocks or moonlight on flowers. He would sometimes take weeks to study the best techniques for depicting them. If he was exploring a particular composition he often made multiple preliminary studies, trying to get everything just right so that when it came to the final version he would be able to work with light and elegant brush strokes, hiding the labor that went into the end product. This was essential to make the best use of the special qualities of watercolor.

Oil paint is a medium that allows artists to cover up mistakes or make corrections and revisions by re-painting with layers of opaque paint. Pencil can always be erased. But watercolor is a more delicate medium. It has a lighter, more spontaneous feel. It is the great paradox of watercolor that it takes a lot of effort to make a painting appear effortless. Watercolor frequently relies on the white of the paper to illuminate semi-transparent colors from beneath. Multiple layers of paint or corrections would muddy the watercolors and destroy the nimble brush work that can be a hallmark of fine watercolor painting.

Gannam passed away in 1965 at age 59. When the Society of Illustrators tried to collect anecdotes about him for a memorial tribute, they realized that his intense work habits kept his peers from learning much about his personal life. The Society’s web site says, “The most difficult detective work connected with this essay was to pin down the late elusive and elfin John Gannam. Many knew a bit about him; mostly the same bits.”

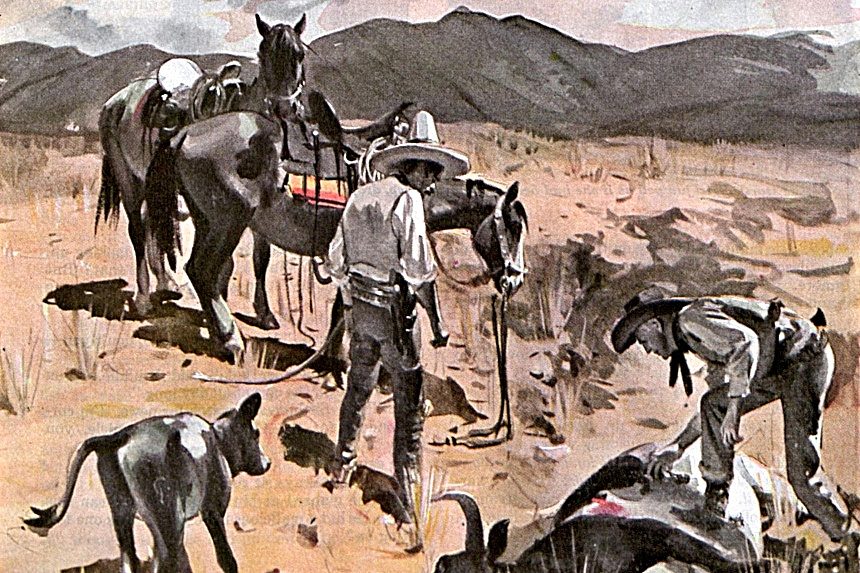

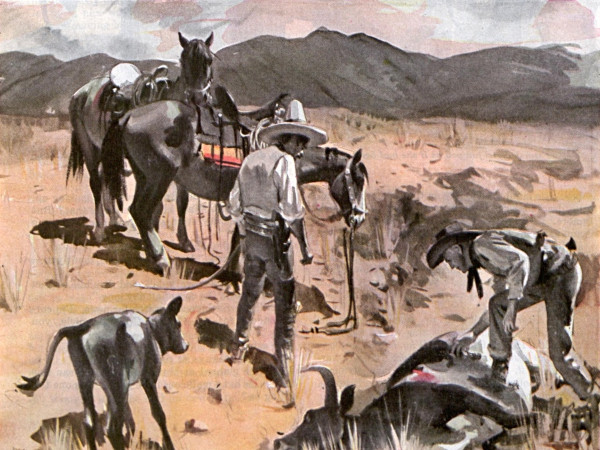

There were few details that people really knew about the art hermit, and some of those details conflicted. It seemed that he took liberties, perhaps to conceal his background as an immigrant. The Post even added to the confusion. The January 25, 1941, issue explains that Gannam was the perfect artist to illustrate a story about cowboys and cattle rustlers because “Mr. Gannam not only comes from the Southwest but he’s also done a little rustling on his own.” The Post quotes Gannam about his history as a horse thief: “It was in Enid, Oklahoma where I was born. I was crazy about horses, always trying to draw them, and dying to own one.” Of course, none of this was true. At the time, he was still technically a Turkish citizen, working on his U.S. citizenship. A friend, Tran Mawicke, challenged him on the fable of his cowboy youth: “John was evasive about how he achieved his results in any medium. I was always curious to know how he knew so much about cowboys….His answer was, “Oh, I have friends.”

Despite these inconsistencies, the Society concluded, “The one fact that everyone agreed upon was what a superb illustrator he was.” And that was Gannam’s true legacy — his work established him as one of the all-time greats.

Featured image: An illustration by Gannam for the Post (©SEPS)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now