Every time I returned to the United States from my ex-pat home in Costa Rica, the first and worst culture shock was the endless array of overhead televisions at the airport, all tuned to whatever dire, hand-wringing news CNN was hyping at that moment.

Living in the jungle, in a town that did not have a newspaper, radio station, or town crier, following any kind of news required booting up your computer and Googling around for the daily horror, something I avoided in favor of snorkeling, chopping down banana stalks, crawling into the stinky chicken coop for still warm eggs, and biking all over town in search of an eggplant.

But once I deplaned it was impossible to avoid the scrolling “BREAKING NEWS”: mass shootings, trumpeting hooey, climactic disasters, talking heads with furrowed brows that indicated the end of the world was at hand. Every person I passed in the airport corridors had their faces slung low over their phones, in search of more bad news, or tweets on the news, or checking how the news was affecting their portfolios.

There was no escape.

If I were visiting my mother, the onslaught continued via Fox News, which was on her big-ass TV 24/7 and always at a volume of 11, as my mother’s constant complaint was that her hearing aids didn’t work. Except when Tucker Carlson was on; then she didn’t miss a word.

If I were visiting my best friend, our never-ending audio background was NPR, with sincere, plummy-toned newsreaders. NPR does come up with a soothing story twice a day, accompanied by a soulful cello. But NPR wants you to know not just the USA but the whole world is going to hell, so we can be alarmed by anti-Semitism in France, Hindu ultra-nationalism in India, and genocidal persecutions in Burma. (Yes I know. I’m still calling it Burma and I’m still calling it Shea. Sue me.) There were ethnic groups in China I had never heard of, and I was an avid National Geographic reader as a child who went on to major in anthropology.

Despite the contrary viewpoints of Fox and NPR, the outcomes were similar: pissed-off mom, convinced her tax dollars went directly into the pockets of the undeserving poor, and wild-eyed, fist-shaking friend who thankfully is also a pacifist or there could have been mayhem.

Beer helped me cope with the onslaught of bad news, but even the coldest brew did not cool down their white hot anger at the ruination of our country that is the quotidian fodder of Facebook, Twitter, TV, radio, and the few surviving newspapers and magazines.

Growing up in the 1960s in the dot on the map that was Duluth, Minnesota, when it came to news, ignorance was bliss. I’m sure there were almost as many horrific events occurring in the States and around the world, but it took a heroic effort to find out about them. We lived in a pleasant bubble where bad things happened to folks living in faraway places most Duluthians (even fellow NatGeo subscribers, who should have benefited from the colorful maps tucked inside every other issue) could not find on a globe.

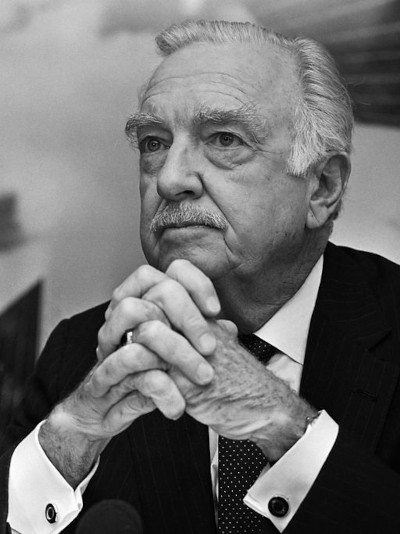

I rarely saw the evening news, delivered by the seriously calm elder statesmen of broadcast journalism, Walter Cronkite (CBS) and Huntley and Brinkley (NBC); the national news aired at our designated dinner hour, which was as regular as a Timex watch.

Like every family I knew, we owned but a single television, which we took turns watching. My mom was addicted to Girl Talk, hosted by the long-forgotten Virginia Graham, and As the World Turns. My dad commandeered the TV on Sunday to watch football; followed by The Twentieth Century, an ancestor of The History Channel, which was 99 percent newsreel footage of bombs being dropped during WWII, followed by The Ed Sullivan Show, a pastiche of ballet, plate-spinning, opera, silk-hatted magicians, yodelers, comedians forced into unfunny family-friendly jokes, contortionists, impressionists, chart-topping bands (“Here’s something for you kids out there”) and every once in a while, to my great joy, the charming but inscrutable Topo Gigio.

Our top-of-the-line RCA television was an immense hunk of dark wood and convex grayish-green screen that was passed off as Danish Modern and so futuristic it would fit into Epcot’s exhibit on “The World of Tomorrow.” The day this new set arrived, everyone on Lakeview Avenue dropped by to admire the first color TV on the block, even though all they got were the still black and white Mr. Ed and Green Acres. The neighbors returned en masse Sunday evening when Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color was broadcast, staying long enough to ooh and aah at the NBC peacock and the fireworks over Cinderella’s castle.

The TV console held pride of place in our living room until my mother caught a redecorating bug that turned her into Madame Maintenon; she went full throttle faux Louis XIV with brocade sofa, chaise lounge, and armchairs, white porcelain caryatid lamps, pale shag carpet (not quite authentic, but shag carpet was mandated for every living room in the 1960s), and marble-topped, claw-footed end tables, chests, and writing desk. Grubby kids were banished from setting foot inside her creation. Maybe she thought Eva Gabor or Virginia Graham might pop in; but the most action that fancy salon saw were her afternoon bridge parties, featuring elaborate desserts, tiny pleated paper cups of Brach’s Chocolate Bridge Mix and cashews, and gossip I strained at the doorway to overhear.

After all her efforts transforming our living room into an ersatz Versailles (although it was actually more Kansas City bordello) mom could not tolerate a piece of furniture that clashed with her ivory and gold color scheme and banished the TV to the basement family room where it went nicely with the fake wood paneling, stained tiles, and beaten up old couch.

On the rare days when the afternoon cartoons signed off with a final “Th-th-th-that’s all folks!” and mom’s hot dish or pork chops or pot roast was slightly late to arrive at the table, I caught a few minutes of the national news, events that completely baffled me. Gorilla warfare? A Bay of Pigs? I was still scratching my head over these animal antics when the first Geritol commercial came on, which was as late as dinner ever was at the Haubner household, and I was hollered upstairs to come eat. My mom was a professional.

Dinner was served in the kitchen, or if we had guests, at the big mahogany table in the dining room, where children were expected to be seen and not heard, especially not heard gagging on Brussels sprouts.

The concept that one could eat and watch television at the same time was reserved for kids and only on Saturday nights, when my parents got dolled up and went out, and my sister and I sprawled on the floor watching Mr. Magoo while searing the roofs of our mouths on Swanson Turkey or Salisbury Steak TV dinners. News on the weekend? What a concept. It was as if the world stopped turning Friday evenings, with “Good night, Chet,” “Good night, David,” or “And that’s the way it is…” from Mr. Cronkite.

At this point, you might wonder where ABC and Peter Jennings were. They were not in Duluth. We had two, count ’em, two TV stations: Channel 6 was NBC, so we got Bonanza (inexplicably my grandmother’s favorite TV show), Dr. Kildare (my mother’s beau ideal, she went to her grave convinced Richard Chamberlain was heterosexual: “He’s too handsome to be one of those”), and Hazel, with the mind-boggling idea that a normal American family could have servants.

ABC and CBS had to share Duluth’s Channel 3. I have a visual image of the guys who ran Channel 3 duking it out over Wagon Train vs. The Lucy Show. PBS showed up around 1967, offering titillating fare such as Washington Week, which competed in the same time slot as the depressing church shows on Channel 3 and 6. Not that it mattered, as my sister and I were frog-marched off to Mass every Sunday morning.

Duluth did enjoy, as did many mid-size towns back in ye olden times, two daily newspapers. In the morning, neither rain nor snow kept our sporadically paid paperboy, Mike Cohen, from his appointed rounds delivering the News Tribune. My father brought home the afternoon paper, the Herald.

Neither of these publications paid much attention to events happening outside of Duluth, concentrating on local news: The first ship of the season to pass under the aerial lift bridge? Viking Days? The Christmas City of the North Parade? Opening week of deer hunting season? Stop the presses!

Duluth newspapers were so focused on hometown happenings that the antics of my own family were covered as if we were Kardashians. I wish I could delve into the dusty microfilm files of the Herald and uncover the photo they ran of my dad riding to work on his Ski-Doo during a record-breaking blizzard, as dedicated to pulling teeth as Mike Cohen was to delivering the newspaper. That photo of my father was front page news.

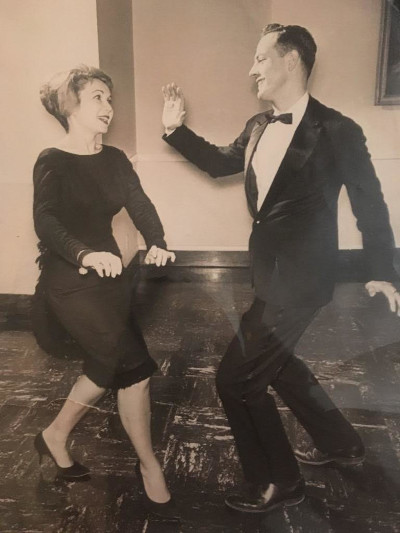

I usually tossed aside most of the newspaper, the part with the boring local and national events, in favor of the second section, which was a wonderful hodgepodge. When my madcap parents (mom pushing 33, an age where she was regarded as a matron of Duluth society) took lessons on that groovy new dance, the Twist, they were awarded a full-page profile. Even I got my photo in the paper for our high school’s production of that old chestnut, “You Can’t Take It with You,” which used to be standard fare in amateur dramatics, as it has a cast of dozens, so even the crappiest actor (me, who barely managed to squeak out my three lines) could tread the boards and then get hammered at the cast and crew party after the second and final performance.

For as long as I have been able to read, I pored over the “Dear Abby” column, a fascinating insight into mysterious adult problems. I would bet the house not a single correspondent ever took Abby’s hard-headed advice. I probably should have internalized a lot of her sensible prescriptions myself. She was our Judge Judy, cutting through the crap and telling her correspondents what they needed to know but did not want to hear: in Abby’s words, they better “Wake up and smell the coffee.” And those mysterious “Confidentials” at the end of her columns? Why has no one done a book on those?

The absolute best part of the 1960s daily newspaper was the entire page devoted to comic strips, which I devoured like buttered popcorn. Peanuts with its cast of goofy kids and not an adult in sight was the one I read first. Here’s to Mr. Schultz’s creations — Mean Girl Lucy; Snoopy, the auteur manque with an exuberant fantasy life; the blanket-loving idiot savant Linus; Pig-Pen with his nebula of dust; Peppermint Patty, the eternal optimist, and hapless Charlie Brown, doomed to have the football snatched away for all of eternity, like a condemned soul in The Inferno — may these perennial children live on in our collective memory, as indelible as any character from Shakespeare or Dickens.

My other favorite comic strips, Dagwood, Nancy, Little Orphan Annie, and Dick Tracy, carried a whiff of the pre-war era thirty years later; in fact, every comic strip inhabited its own unchanging universe. Kind of like Duluth.

My mother shook her head with dismay when she caught me reading the comics; she believed such fare would lower my IQ. (Actual comic books, outside of the prissy Classics Illustrated, were as verboten in the Haubner household as pop or pre-sweetened cereal). How sad, I thought, to be so old that you wouldn’t find Beetle Bailey entertaining. I’m afraid I reached that milestone long ago.

Since I have zero interest in athletics, unless I can be in Wrigley Field on a breezy summer day drinking a watery beer, I cannot tell you anything about the sports coverage of either paper, except that the top stories were high school sports, since every reader had a son, grandson, cousin, and/or nephew who played something (cheerleading, the sole option for girls, had the most cutthroat competition for a spot on the squad). The University of Duluth Bulldogs rated a few column inches, as did the Vikings, and the mostly woebegone Twins (although one September day in 1965 when the Twins finally made the World Series, everything stopped at Woodland Junior High to listen to the final game broadcast through crackly classroom speakers). There was no Minnesota professional basketball team, and oddly enough, for a state that is iced in eight months a year, the North Stars hockey team did not show up until 1967.

My primary source of news came from My Weekly Reader, which had special editions for each elementary school grade. I don’t remember how much My Weekly Reader dumbed down the 1960 Presidential election for second graders; I do remember the side-by-side Ben Day dot photos of Richard Nixon, who looked scary enough to be a Dick Tracy bad guy, versus Jack Kennedy, as handsome, clean shaven, and white-toothed as Dr. Kildare. Kennedy would have been my choice even if our parish priest hadn’t threatened the congregation at every October Mass that year with excommunication if they didn’t vote the Catholic in.

It wasn’t exactly news, but rather thrilling dispatches from the great beyond that arrived every month in National Geographic: daring photos of exotic tribes with bare-breasted women and men in penis sheathes, necks elongated with steel rings or earlobes stretched out to shoulders, along with the world’s deadliest snakes, spewing volcanos, ice-blue glaciers, and cute koalas and meerkats.

The Haubner family received a few other magazines, although after my mom’s squirrel-size poodle Shay-Shay bit the postman we lost the privilege of home delivery and were forced to pick up all our mail at the P.O.

My mother had a lifetime subscription to Ladies’ Home Journal and McCall’s, women’s magazines chock-full of aspirational interior decorating tips, fashion for middle-aged, middle-class ladies (along with those risqué “I dreamt I went to the grocery store in my Maidenform bra” ads), and recipes that called for either a can of some variety of Campbell’s cream soup or a container of Cool Whip. McCall’s did have Betsy McCall, a paper doll who appeared in every issue, along with two adorable outfits. I was not allowed to take scissors to Betsy McCall until my mother had gone through every boring page of that month’s issue; and since Betsy was made of flimsy magazine stock, neither she nor her wardrobe survived more than a few days.

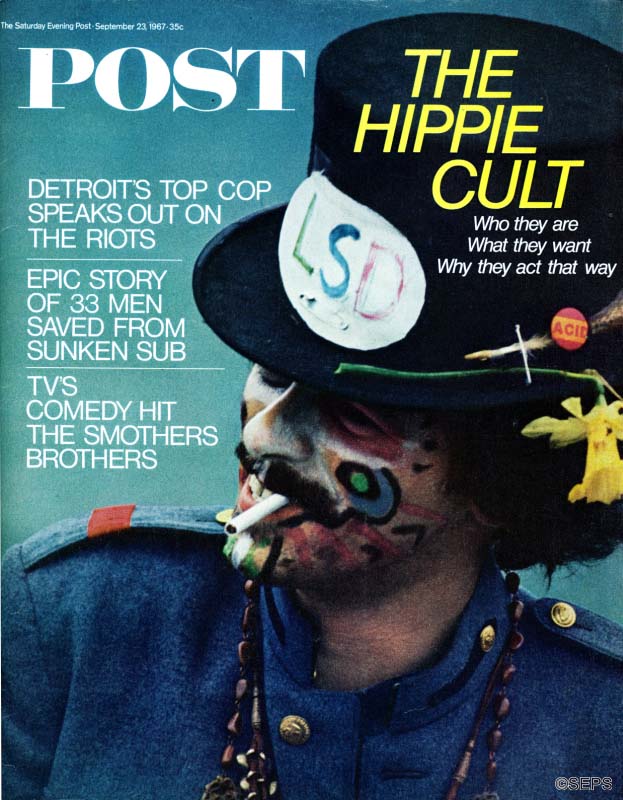

Like every family in America we also got Time and The Saturday Evening Post, magazines that provided weekly peephole glimpses into what was going on in the world outside of Duluth. I was the only one who read these magazines; I hoarded them on the floor of my bedroom until my mother decided it was time for a cleaning tornado and tossed them out, along with any contraband Mad magazines I had smuggled in.

At some point, Time developed an alarming penchant for sensational crime stories: The Kitty Genovese tragedy, the torture and murder of Sylvia Likens, and Richard Speck and his problems with student nurses. With the grainy photos and Time’s affectless prose it was like reading ghost stories; they still scare the crap out of me.

The Saturday Evening Post provided more uplifting entertainment, including a slew of great fiction: I will knock down anyone who does not admit that “True Grit” by Charles Portis is an American Classic; why it is not taught in schools is a mystery.

When I was in ninth grade, the Post ran a cover story on the Haight-Ashbury scene filled with dreamy photos of alluring long-haired hippies in romantic gypsy costumes, stoned out of their gourds. I carefully tore those pages out, Scotched-taped them on my bedroom walls, and stared at them hoping to magically transport myself from the black and white world of Duluth into that Technicolor Oz, which seemed a lot farther away than over the rainbow.

News seemed to reach Duluth as sluggishly as if it were transmitted by telegraph wire or Pony Express. Zenith City was an isolated kingdom; we were practically Canadian! Until the day three bullets from an infantry rifle were fired from a book dispensary.

On November 22, 1963, our fifth grade class was screwing around as usual (except for Miss Goody Two-Shoes here, reading a contraband Peyton Place under my desk), boys giving each other noogies or Indian burns or tossing spitballs, girls absorbed in creating and swapping origami paper fortune tellers, everyone trying to see how much mischief they could get into before our elephantine teacher, Miss Johnson, hauled herself out from behind her desk to attempt to wrest control, when the ancient Bakelite phone on the classroom wall rung into life for the first time in years.

Miss Johnson picked up the earpiece and the blood drained from her face, probably pooling around her impossibly thick ankles.

“Everyone has to go home. If you take the bus go wait at the bus stop and the bus will be there soon.”

I was terrified. Something very, very bad had happened. Only a few years earlier we learned to duck and cover in case of nuclear attack; the black and yellow “Fallout Shelter” signs still hung in the school hallways. Congdon Elementary had never closed in the middle of the afternoon. If an Antarctic blizzard descended, we stayed in class and struggled our way home at 3:00 like Amundsen heading for the South Pole.

I walked to my Lakeview Avenue house alone, fretting over the dreadful possibilities. Were we under alien attack? (I had just seen War of the Worlds at a special kids’ matinee at the Norshor Theatre.) Or could the evil Soviets have bombed Minneapolis? Did Fidel have missiles aimed at the United States again?

When I got home I headed down to the basement to turn on the TV, fully expecting to see Gort from The Day the Earth Stood Still annihilating the White House.

The news was much worse. My mom was crumpled on the couch in front of the television, tears cutting through her makeup. This frightened me even more, as the only time I had seen my mom cry was when we had distant relatives decide to extend their stay with us another week.

Mom had been watching As The World Turns (which was filmed live!) when her show went off the air and a voice announced that President Kennedy had been shot in Dallas. While mom was as apolitical as a fire hydrant, she was a sucker for a handsome face, and even begrudgingly admitted Jackie was the superior interior decorator.

I tried to make sense of what we were hearing and seeing. The President had been shot? Didn’t he have all those Secret Security guys? Didn’t everyone love him and his picture book family? Who would do such a thing?

That day I walked out of school and into reality: horrible things can happen, even if you were the President of the United States, or his charming wife, or his adorable children. In our small town Babbitt bubble of loving families, men with good jobs, and as Garrison Keillor knows, where every child is above average, the world could change in a heartbeat.

While that one great heart was stopped in November, a million teenage hearts were set afire a few months later. On February 10, 1964, I walked into a classroom of pre-teens girls whose hormones had begun sending out those confusing messages about boys and love and sex, 15 fifth graders all besotted by the Beatles.

I missed the main event. The night before, my family had made yet another miraculous car ride home from a tipsy Sunday of bottomless servings of 7 & 7s at my grandparents’. I climbed the stairs to my room to find something to read. My father took a highball to the basement to watch what was left of Ed Sullivan and made the paternal decision that his 10-year-old-daughter was too young to enjoy a rock and roll band from England; an Italian mouse or Señor Wences and his talking fist were more age-appropriate.

The psycho obsession with the Beatles among the girls I longed to be friends with, or at least accepted by, sent me to our one and only music radio station, WEBC, Channel 56 (FM had yet to be invented) to figure out the attraction.

WEBC played tunes from the Top 40, starting with the #1 record and going down the count, interspersed with commercials for Ski Hut and Jeno’s Pizza Rolls, until they got to #40 and started over, ad nauseam. Riding in our Chrysler Newport I heard “Paint it Black, “Angel of the Morning,” “It’s the Time of the Seasons” and “Like a Rolling Stone” interspersed with the tunes my mom crooned along to: “Moon River,” “I Left my Heart in San Francisco,” and Dino’s “Everybody Loves Somebody Sometime.” When Johnny Cash’s “A Boy Named Sue” hit number one and stayed there for an eternity, I thought I would lose my mind.

My every cell absorbed those siren anthems to a revolutionary era, one where what my parents thought and what my teachers taught didn’t matter. The world was a-changing and I wanted to be part of that new becoming, the dawning of the Age of Aquarius, a long-haired girl in a gauzy dress, dancing barefoot in a park that did not feature a statue of Leif Erickson and a fake Viking boat.

Those songs of my youth are still around. My favorite beach bar in Puerto Viejo, Costa Rica, Tasty Waves, always had The Who and Jimi Hendrix and The Kinks in the rotation. I sipped my Corona and shook my head: it was as if the juke at my Dinkeytown college dive played “Chattanooga Choo Choo” and “Tea for Two:” music a half a century old.

I used to marvel that my grandparents had been alive to hear Lindbergh cross the Atlantic and to watch the Eagle landing on the moon. Now I have passed through an age of wonders, going from a transistor radio pressed to my ear to access to a universe of music, a multitude of stars to discover. I’ve gone from radio stations that delivered farm reports and the Top Forty to…whatever commercial radio is now.

Even that old clique of gathering around the water cooler to discuss L.A. Law or Cheers the morning after has vanished, most likely never to return; even if we go back to the office, we will bring our own pedigreed hydrators, and it is unlikely any two of us would have watched the same program the night before.

I am grateful to have grown up in a time and place when news was what happened to other people, where there was but a single screen in each home that showed nothing scarier than The Twilight Zone. I believe that all of us above average children of those small Midwest towns, now grown to ordinary middle age and senior citizens, all of us would happily slip back to that simpler, insular and yes, probably slightly stupider era when all we knew was what we read in the Herald or what Mr. Cronkite told us.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Another great, descriptive, well told tale of your youth; linked to the present day at the end. We love your stories here over the past several years. They’re all modern Saturday Evening Post classics. Thanks Gay.

There’s so much here, I’ve made a list, and will take things in order.

Before I do, thank you for reminding me of things I’d forgotten. When you’re a kid, you’re certain you’ll never forget them. Also, it is amazing how close to uniform life was all over the middle class country, and yes, most of us wish we were back in it.

Before the list: I just heard the radio announcer deliver a weather forecast for Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Indigenous people all over America would be bemused by that. Now, in order:

1. Virginia Graham. In the mid 60s, my mother went to see her in a personal appearance in Houston. Somehow, my mother, whose right hemispheric I.Q. may have been 70, got lost trying to find her way through the corridor to the theater. She thought to ask directions from whoever might be in the room with the open doorway. It was Virginia Graham. My mother said she was as nice as her TV persona.

2. I grieve your tornado loss with you, as one who knows. For me, it was the Hardy Boys, which in years to come my calculating mother perceived may have been quite a money throwaway.

3. I loved TV dinners, but was made ecstatic by two beef pot pies, with cottage cheese.

4. In regard to Kitty Genovese, there is a brilliant documentary, The Witness, which is probably still on Amazon Prime. Its last ten seconds may be the most haunting thing I’ve ever seen.

5. Charles Portis! As Ron Rosenbaum wrote of Portis forty years ago, he may have been America’s great, unknown writer. Instantly, I’d name The Dog of the South the funniest novel I’ve ever read, and Norwood a close second.

6. It’s finally happened. I thought ours was the only school in the country whose dimwitted major domo, in our case, the principal, kept our teachers from telling us the news about the Kennedy assassination. She wanted the thrill of telling us herself over the p.a., I guess. And you don’t know how right you are about the terror. One boy in my class had what in adult life I would understand to have been a panic attack.

A marvelous article.

Your stories remind and confirm to me some of the most pleasant memories of my life. Almost can’t get enough…

Thank you. More, please.

Such impressively-detailed memories of growing up in Duluth! Thanks for the trip back home. I’ll share the story’s link with my Central Class of ’70 friends who’ll no doubt appreciate it as much as I did.

I grew up in Duluth too, several years before you. And life was just as you described it. I went to Congdon Park grade school and even had Miss Johnson as my teacher. This is an incredibly accurate and charming read. And your parents were adorable. Give us more!

Bravo to Gay Haubner, who has once again entertained us with her wit and charm.

This is a nostalgic and excellent read! An accurate depiction of growing up in Duluth back in the 60’s. More please.

Gay

You hit a homerun with this story. We had the first color tv so all the neighbors

would come over to watch the wonderful world of Disney every sunday. We got ABC tv in 1965 I believe. The son of the owner went to school with me at Saint John’s in Woodland. I’m surprised you didn’t mention Joe E Hylek your friendly insurance

man. He hacked up his wife near where you lived. Great story though.

This brilliant essay made me smile, laugh out loud, tear up, and remember those days with such clarity. I will be curling up in my favorite comfy chair and visiting this over and over. What an amazing piece!