—From “Clearing the Skies for the Sugar-Poisoned,” June 9, 1923

Could anything more unlikely, more monstrous, be well imagined than that sugar, our priceless fuel, the chief source of all our energy and heat, should suddenly refuse to burn in our body furnace as if it were slate instead of anthracite? Yet this is literally what happens in this strange malady, diabetes. If we can’t digest sugar, it’s no use to eat starch, because all the starch we eat — bread, rice, cereals, puddings, potatoes — has to be turned into sugar — glucose — before we can burn it in our muscles. Our body engine is a sugar motor.

But for the luckless diabetic, it is a case of sugar, sugar everywhere, but never a scrap to burn. His problem is a distressing and difficult one — how safely to cut out of his diet the one fuel which normally gives him nearly two-thirds of his energy for work and for life. But Nature is a wise and resourceful old mother. And, aided by reasonable regulation of the diet, a sort of tightrope balance is caught and held. And there the matter has hung for centuries even though every conceivable change has been rung upon modifications of diet and drink, but without much success, except in delaying the course of the disease and making the patient’s condition more comfortable.

But a few decades ago our knowledge of the chemistry of our bodies and of that marvelously efficient and ingenious stream of backward and forward interchanges between our food and our body stuffs, our work and our wastes, our buildings up and our breakings down, which we term metabolism, had become sufficiently accurate to enable us to attack the disease from the other end of the line, so to speak. We are now happily able to announce the first positive step toward the answer of the fateful riddle, one that gives new hope to all diabetics.

This is no less than the discovery of the hormone which enables our bodies to burn sugar and whose absence makes us diabetic. And what is of vital practical value, this hormone, procured from the bodies of animals and injected into the veins of diabetics, will clear their blood of surplus sugar, enable them to digest an almost normal amount of starch and sugar in their diet, and greatly improve their condition in any respect. Some patients, in fact, have already regained their normal weight and strength and gone back to work on an ordinary diet.

It is, of course, far too soon even to mention the word cure in a long-lasting and obstinate disease like diabetes. All that can be claimed is marked temporary improvement, and to raise false hopes of anything further in the bosoms of our quarter of a million diabetics in the United States would be deplorable. But we can fairly say that this improvement is of a different type from any won before, and that, whatever its permanent effects, the new remedy is almost sure to be a great practical addition to our methods of treating the malady.

This article is featured in the September/October 2021 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

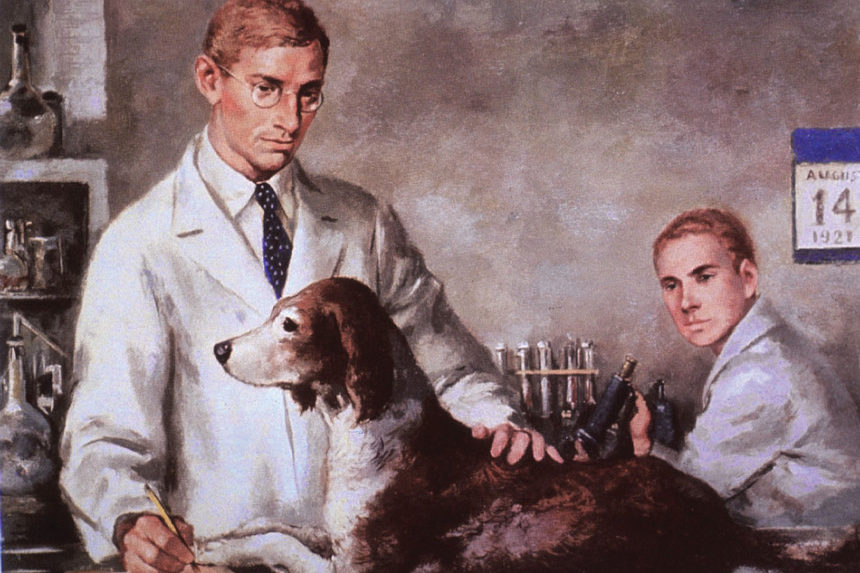

Featured image: Dogged determination: Frederick Banting and Charles Best, with a diabetic dog they kept alive through injections of insulin. Banting and another researcher, J.J.R. Macleod, were awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine. (Everett Collection Historical / Alamy Stock Photo)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now