In the days following Pearl Harbor, Americans forgot their differences and drew together to prepare to enter World War II. But that wasn’t the case at the beginning of the previous war.

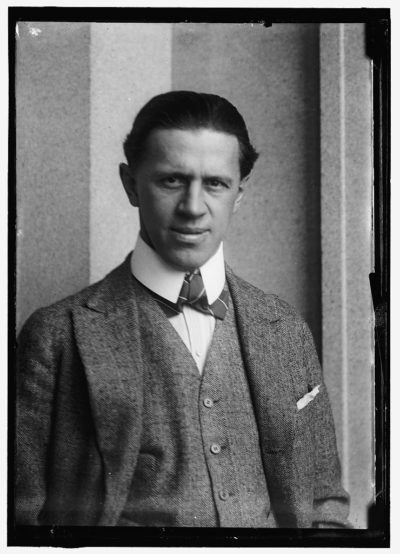

When the U.S. government entered World War I in April 1917, it needed the support of an enthusiastic public. Unfortunately, many Americans didn’t see any reason for the U.S. to join the fight. To stir up enthusiasm, President Woodrow Wilson asked journalist George Creel to launch a national press campaign to unite the country behind the war effort. Or, as Creel said, “to weld the people of the United States into one white-hot mass instinct.”

Creel’s Committee on Public Information produced a mountain of material on America’s progress in the war. The news division placed their propaganda in 20,000 newspaper columns each week, according to Creel.

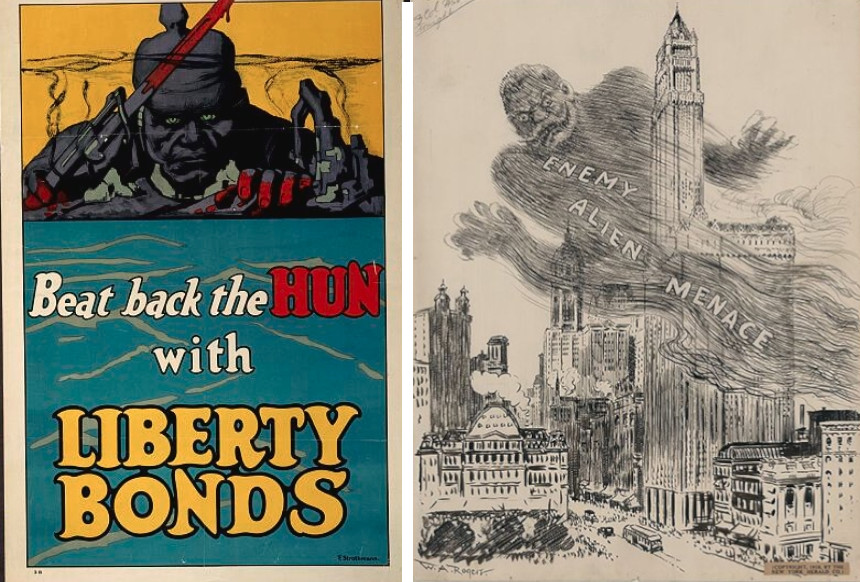

While positive stories helped sell war bonds and attract recruits, Creel found they weren’t as effective as demonizing the Germans.

Many Americans were ready to believe Germany was trying to destroy the United States. They had been alarmed by the wave of German immigration that peaked in the 1880s and resulted in nearly three million German-born immigrants. There were more 550 German-language journals being printed in America. Nativists were outraged that German was being taught in schools.

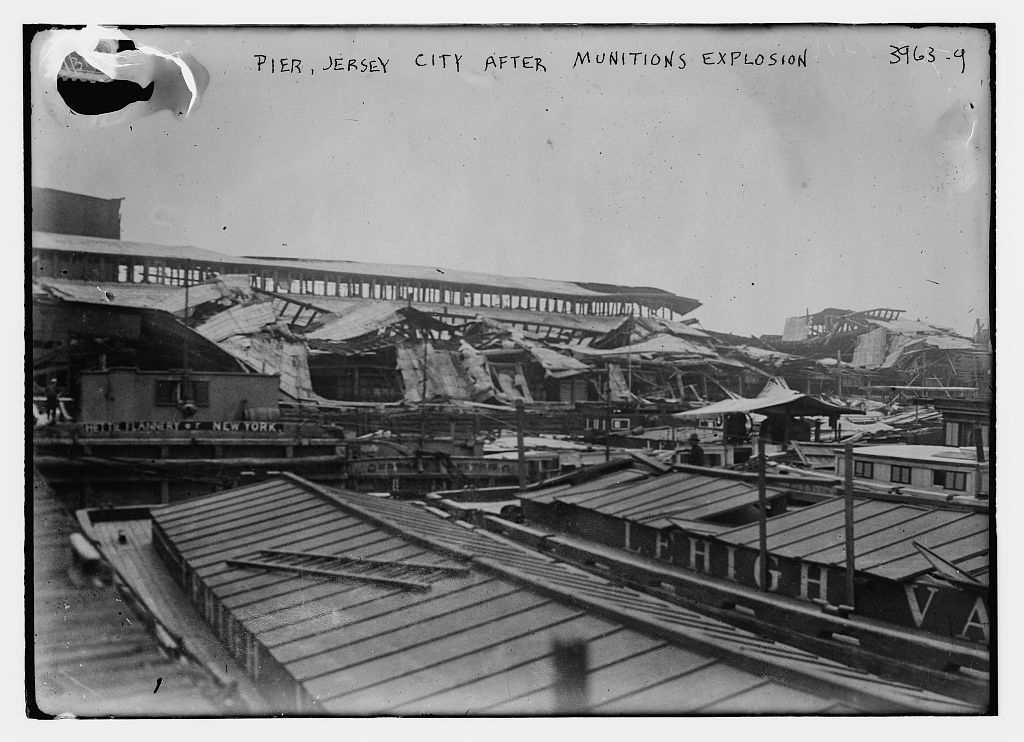

Anti-German hostility had been further provoked by the German government’s covert actions against the U.S German saboteurs had destroyed the munition depot in Black Tom, New Jersey, killing four Americans in the explosion and even damaging the statue of liberty.

And then there was the intercepted Zimmerman telegram to the Mexican government from the Germans, offering to return the land of the southwestern American states to Mexico if she allied herself with the Central Powers.

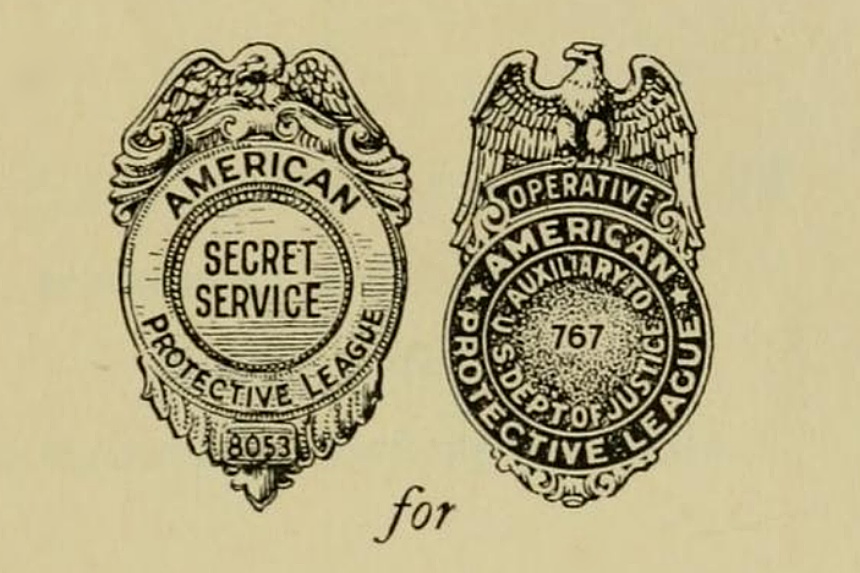

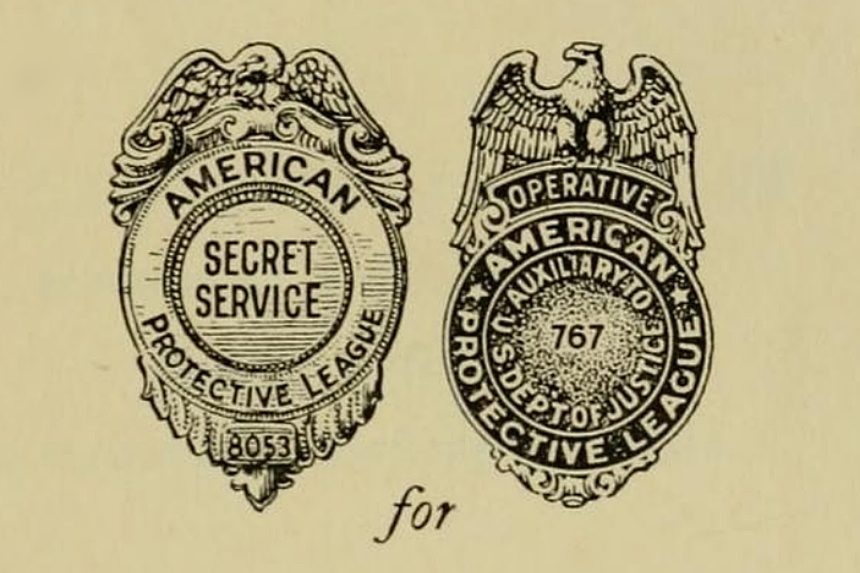

The Bureau of Investigation — forerunner of the FBI — was tasked with tracking down German saboteurs and spies in America with just 200 agents. But a Chicago advertising executive, A. M. Briggs, suggested a volunteer force could gather information on possible enemy actions in America. With President Wilson’s blessing, the Bureau launched the American Protective League (APL), a volunteer force of civilians who, as Attorney General Thomas Gregory said, would be “keeping an eye on disloyal individuals and making reports of disloyal utterances.” Eventually, the APL grew to 250,000 members in 600 cities.

Members had no official powers. They weren’t allowed to carry firearms or make arrests. After paying dues of 75¢, however, they were authorized to wear a badge that read “American Protective League – Secret Service.”

They gathered information on neighbors, friends, and especially strangers who seemed insufficiently pro-war or anti-German. They submitted reports to the Justice Department on neighbors they suspected were hoarding food, buying on the black market, checking out too many German books from the library, or playing German music.

League members participated in raids on homes and offices. They also engaged in blatantly illegal searches. In 1919, Emerson Hough, a frequent Post contributor, wrote The Web, a book lauding the exploits of the APL. He described how members would gather information on a suspect. You simply had to find “an agent of the building” who, like yourself, was wearing a concealed APL badge. He would instruct a janitor to open the suspect’s office.

Once inside, members would simply open safes or go through desk drawers. Personal effects were examined. Documents were captured on camera. The process was simple and quick, wrote Hough, “and the drawers and doors are locked again.” As to the legality of this procedure, Hough explained that “the serving of a search warrant would have queered the whole case and would not have got the evidence. The camera film has it safe.”

Attorney General Gregory excused such illegalities. “I am convinced,” he said, that zealous members “were led into this breach of authority by excess of zeal for the public good.”

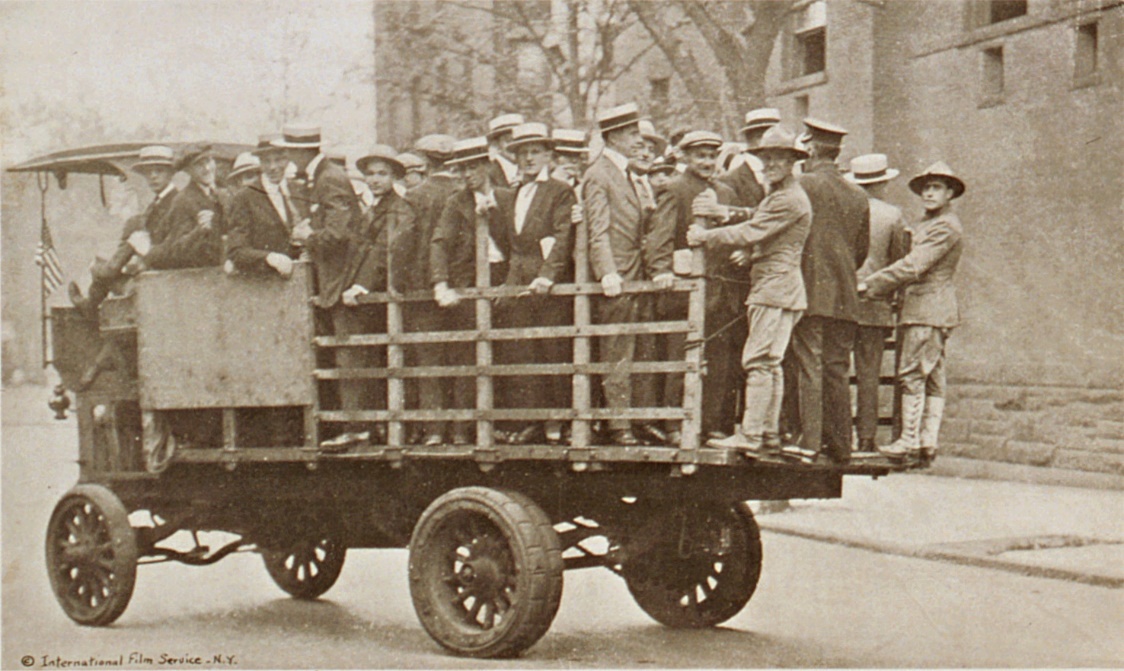

Members were also diligent in conducting “slacker raids.” They would stop men in streets, saloons, ballparks, movie theaters, and restaurants, demanding to see their draft registration papers, which all draft-age men were required to carry. Those who weren’t carrying their papers were arrested and held until their status was verified with their draft board, which might take weeks. In New York, more than 60,000 men were detained, of which 1,300 were determined to be draft dodgers. The other 58,700 were eventually released.

Some members decided to administer their own justice by assaulting men they suspected of being un-American. In Audubon, Iowa, Lutheran pastor Rev W. A. Starck and another man barely escaped being hanged in the public square before deputy sheriffs intervened. A Denver man who refused to kiss the flag was rushed to the hospital in serious condition after being towed by a noose around his neck fastened to a truck. Dr. J. C. Bienneman in La Salle, Illinois, was dropped into a canal, fished out, forced to kiss the flag, then ordered to leave town. For not contributing to the Red Cross, Rudolph Schwopke of Emerson, Nebraska, was tarred and feathered.

Much of this violence occurred outside city limits, beyond the jurisdiction of local police. If attackers were identified and arrested, they were rarely tried, and even more rarely convicted. Jurors hesitated to pass guilty verdicts out of fear they would appear disloyal too.

Some members expanded the scope of enemies to include trade unions. They helped to break strikes, or went undercover to hunt down disloyalty among union members. Gangs of APL members would break up meetings of socialists and members of the radical labor group Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

The APL wasn’t alone in its efforts. Other groups sprang up to ferret out covert enemies. There was the Anti-Yellow-Dog League, the Knights of Liberty, American Rights League, Boy Spies of America, American Defense Society, Sedition Slammers, National Security League, and the Terrible Threateners.

In “Swat the Spy!” which appeared in the January 12, 1918, Post, David Lawrence offered advice to vigilant Americans. He warned them against acting hastily. Neighbors of German birth or strangers with foreign accents who moved into the neighborhood didn’t need to be immediately suspected. And Americans who spoke out against the war didn’t need to be reported IF they had made their remarks before the U.S. declared war on April 6, 1917, and their “Americanism was sound.”

Readers were advised to pay especially close attention to men who could have been pretending to be army officers. “Some real spies are believed to have enlisted in the American Army,” Lawrence wrote. Also, Americans were to pay attention to any German waiter in a restaurant; many spies got work as waiters to eavesdrop on important conversations.

When the war ended in November 1918, there was no longer any need to find German spies or draft dodgers. Many members asked that the Justice Department keep the League active to hunt down Bolsheviks and American supporters of the Soviet government.

But a new attorney general, A. Mitchell Palmer, quickly made it clear he wanted no part of volunteer intelligence and surveillance. He immediately released 10,000 aliens of German ancestry who had been detained under the charge of disloyalty. He labelled the APL information a collection of “gossip, hearsay, information, conclusions, and inferences.” It was the sort of information that couldn’t be used without endangering individuals who were probably innocent.

Unfortunately, the vigilante spirit wasn’t easily quelled. Socialists, communists, anarchists, and IWW members were frequently assaulted in the coming years. The KKK underwent a vast, nationwide revival and the number of racial lynchings rose. Fortunately, the violence seemed to fade away about the time the bull market of the 1920s brought general prosperity to the nation. It led Americans to hope they’d seen the last of the waves of vigilantism that had, repeatedly in the 1800s, turned citizens against each other.

Featured image: Illustration from The Web by Emerson Hough, 1919 (Internet Archive)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

An intelligent appraisal would rank Woodrow Wilson as one of America’s two or three most destructive presidents.