On the morning of February 3, 1943, the SS Dorchester, a U.S. steamship, was carrying more than 900 passengers including personnel and soldiers. To be more precise, there were 904 men aboard. Those last four were George L. Fox (a Methodist minister), Alexander D. Goode (a rabbi), Clark V. Poling (a Dutch Reformed pastor), and John P. Washington (a priest). Their religious services on board were sparsely attended, but still they provided comfort and solace through their calm presence.

The ship was on her way through the stormy late-winter seas of the Atlantic to a military base in Greenland. The passengers were mostly soldiers, many of whom were young and inexperienced. Fear was already rising among the men as the Dorchester began her journey from Newfoundland, and with good reason: Coast Guard sonar had informed the captain that a submarine was lurking somewhere in the icy brine below them. The Dorchester was already struggling in the rough sea, and this alert was enough to push her captain to tell the men to sleep in uniforms and be ready for hostile engagement. They were also told to wear their life jackets to bed, but the discomfort of army cots (even without a bulky life jacket) and the heat of the engine pushed many of the exhausted men to disregard this order.

At approximately one o’clock in the morning, the German U-boat they’d seen via sonar broke through the water’s surface. Its torpedoes hit the Dorchester on her starboard side. A hundred men were killed instantly. All radio connection was lost in the blast.

The ship began to take on water.

The passengers exploded into a panic. The men below deck were mostly without life jackets, and many were still in their sleeping shirts, not that day clothes would do much against the frigid water of the Atlantic Ocean. When they made it above, they would realize that the sweaty heat of the sleeping quarters was a warmth they’d want to remember. There weren’t enough lifeboats. Rafts thrown into the water were carried away by the knocking sea before they could be stocked with people.

Without life jackets, there was nothing to keep them above that water. Even with life jackets, they would likely survive only minutes in the freezing water.

Interviews provided by the Four Chaplains Memorial Foundation recall the chaplains dispersing into the chaos to calm and to pray. More people emerged from the bottom decks. The chaplains began to hand out life jackets along with their kind words. But there weren’t enough: there were more men than flotation devices.

Finally, one soldier cracked. He came to one of the chaplains (history does not know which) and told him, in fear, that he’d lost his jacket. He couldn’t swim.

The chaplain removed his own and gave it to the young man. “I’m staying,” he said.

The other three chaplains followed suit.

The ship remained afloat for less than half an hour after the initial hit. As she began to go down, the four chaplains — the minister, the rabbi, the pastor, and the priest — locked arms and stayed on deck. They had all guaranteed their own deaths on the small chance that they might help one of the other men on board. The ship listed. The Dorchester went down.

The chaplains, of course, did not survive. That is not the kind of miracle that this story is about. Of the 900 men on their way to Greenland, 230 were rescued. That small number would have been smaller by four if not for the bravery and decisive action of a few men.

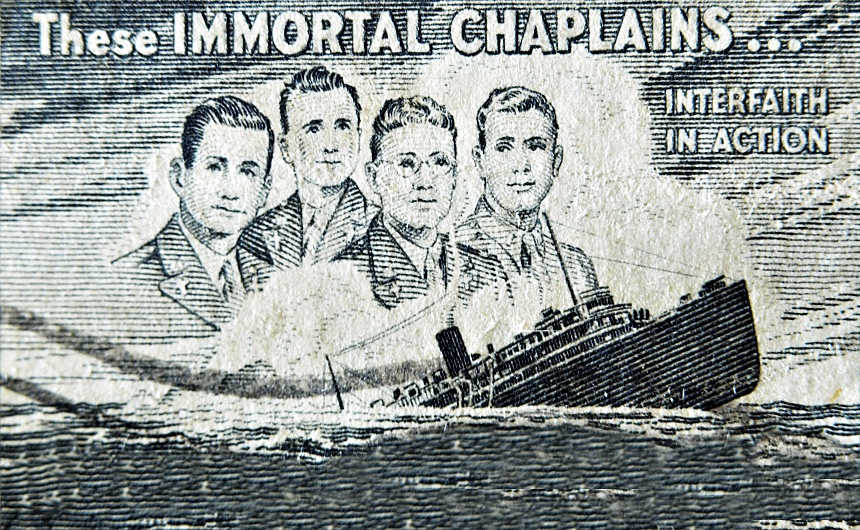

Featured image: Modified image of a U.S. postage stamp, circa 1947, honoring Goode, Poling, Fox, and Washington (Shutterstock)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now