There’s a great deal that’s wrong with the many recent, current, and proposed laws that would remove books from classrooms, curricula, school libraries, and other educational spaces. These proposals attack the very core of what educational communities and conversations should be and do, and would if enacted produce subsequent generations of young Americans who know less and less about our histories and stories. But these anti-education laws are also profoundly ironic, because the truth is that, even in 2022, American classrooms and reading lists are still far too often and too fully dominated by white authors and stories.

I’ve seen this firsthand with my sons’ experiences in a generally progressive and certainly impressive public school system in Massachusetts. In their 9th grade English classes (with different teachers), each of them has read a series of canonical American novels by white authors, familiar texts that I myself read in school three decades ago. This static and still overwhelmingly white curriculum isn’t a given and can be productively shifted and expanded. There are parallel works by Black authors that could be substituted in each case, books that offer many of the same themes but feature a far wider range of voices. To present a more genuinely inclusive American story, we need to read more Black authors and works like these, not just in February but all year long.

The most familiar book that my sons read in 9th grade would have to be Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), a work that has consistently topped polls of the favorite or “best-loved” American novel. Lee’s book is both beloved and so frequently taught at the middle and high school level not just because it’s a moving coming-of-age story of its youthful protagonist Scout Finch, but also because it is an examination of racism and prejudice on the one hand and ideals and activism on the other.

As I argued in a 2021 Black History Month presentation for my university’s library, however, there is another coming-of-age novel from the same era that presents those themes with far more depth and nuance, while still offering many of the same pleasures as Lee’s book. That novel is Gordon Parks’s The Learning Tree (1963), a semi-autobiographical story inspired by Parks’s childhood experiences in early 20th century Oklahoma. Parks focuses on a few eventful years in the life of his youthful protagonist, teenager Newt Winger, but through his third-person narrator also moves across many other characters, families, and stories in the town of Cherokee Flats, touching on both universal coming-of-age themes and much more specific histories like lynching and police brutality in the process. Like Mockingbird, Parks’s book was also adapted into a film, in this case one directed by Parks himself, making him the first African American to direct for a Hollywood studio (one of countless achievements in his inspiring career and life). Parks’s novel and film could be taught together in place of Lee’s familiar book, offering all students a perspective on 20th century American childhoods, communities, and conversations that interestingly overlap with — yet also go far beyond — the conventional white world of Scout and her family.

I wasn’t surprised that my sons both read the beloved Mockingbird in 9th grade, but I have to admit I was stunned that they also read another book familiar from my own 9th grade class 30 years prior: John Knowles’s A Separate Peace (1959). Knowles’s story of the fraught relationship between two teenage boys at a New England prep school, set against the backdrop of World War II, has some interesting themes of identity, community, and the dangers of lying to ourselves and others about who we are. But its characters and world are strikingly elite, narrow, and homogeneous for 21st century classrooms and audiences.

There are of course countless books from our own era about teenage life, all of which offer a more diverse cast and world than Knowles’s novel. But even if a more “classic” text is required, there’s a novel published in the same year as Peace that likewise presents a far more diverse story of American childhood and community: Paule Marshall’s Brown Girl, Brownstones (1959). Marshall, the daughter of a Barbadian immigrant father and a single mother who raised her and her siblings in 1930s Brooklyn, creates in her debut novel’s main character Selina Boyce a protagonist who is somewhat autobiographical but also deeply representative of the perspectives and experiences of second-generation immigrants, African Americans, mid-20th century young women, and other intersecting identities. Selina can speak to all 21st century American teens while at the same time opening a window into a very different era and world.

After A Separate Peace, my sons’ 9th grade English classes turned to another very familiar book, and without question one of the most compelling and enduring short American novels: John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men (1937). Steinbeck’s moving book depicts a Great Depression world of migrant labor and poverty, of a friendship and partnership tested by prejudice and tragedy, and, in its famous main character Lennie, of disability in a period when such experiences were generally even left out of cultural works or depicted in deeply problematic ways. It’s a challenging book in ways that 9th graders certainly should be challenged.

Yet at the same time, reading Steinbeck’s book (especially as part of an overwhelmingly white curriculum) reinforces narratives of the Depression, Dust Bowl-era migrant labor, and the American working class as largely or centrally white. Whereas if we substitute another novel published in the same year, Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), we can engage with many of the same themes while recognizing their intersections with issues of race, gender, and region. Hurston’s protagonist and storyteller Janie Crawford, as well as her trio of distinct and representative husbands and the all-Black yet still quite diverse Florida communities through which she journeys, collectively can help expand students’ understandings of work and poverty, community and relationships, and Depression-era America.

There are similar alternatives for every familiar, canonical work still being taught so frequently. Across my 20 years of college teaching experience, for example, I have found that the single book students are most likely to read at some point in high school is F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925). I’m about to start teaching Gatsby myself, so I get it — but what would it mean if those students also, or perhaps instead, were to read Nella Larsen’s Passing (1928), a novella that is just as beautifully written and engrossing as Fitzgerald’s book, depicts many of the same themes of identity and community and the American Dream, and opens up themes of race, class, gender, and sexuality in deeper and more thought-provoking ways than Gatsby?

Black History Month gives us a good reason to start sharing and discussing books by Black authors. But we need to read more Black authors every month of the year, in every classroom and educational space, and here in 2022 more than ever.

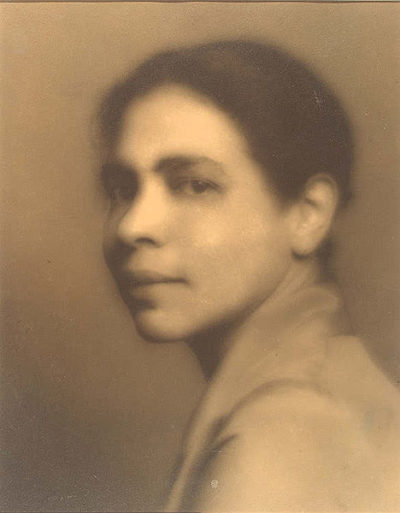

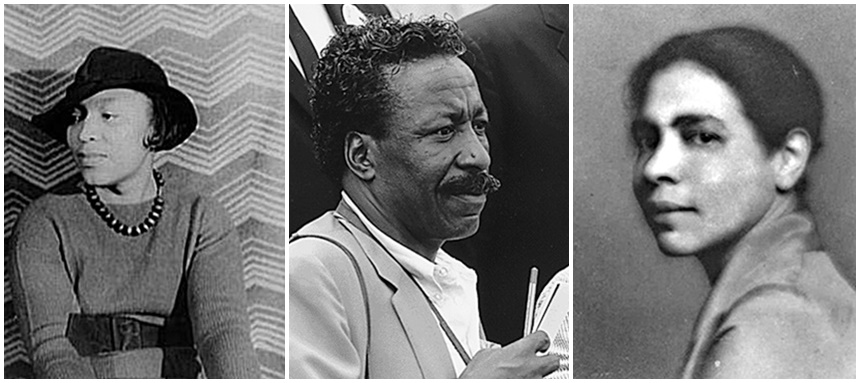

Featured images: Zora Neale Hurston, Gordon Parks, Nella Larsen (Wikimedia Commons)

Additional Book Recommendations

- Frances E.W. Harper, Iola Leroy (1892)

- Charles Chesnutt, The Marrow of Tradition (1901)

- Pauline Hopkins, Of One Blood, or, the Hidden Self (1903)

- James Weldon Johnson, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man (1912)

- Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (1952)

- James Baldwin, Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953)

- David Bradley, The Chaneysville Incident (1981)

- Toni Morrison, Beloved (1987)

- Yaa Gyasi, Homegoing (2016)

- Colson Whitehead, The Nickel Boys (2019)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I wonder if some of the legacy books used in what used to be called English Literature classes may have been used because they were the best available at the time and also were excellent examples of grammar, and were carefully edited (which seems to be lost). Once identified as exemplary, it was easy to keep going with a known good product.

Many of the old books weren’t chosen only because of the stories but also the style and acknowledged quality of writing. Good writing is also an art form and beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Too few understand the details of the brushstrokes and even fewer recognize what it is. They stick with what they see others using in order to fit in. How many people read only what has made the best seller list?

When a lot of these classics came out, they were controversial. After the dust settled, people just stayed in their lanes. That leads to mediocrity, or worse.

Ben Railton gives readers new insights into America history every time he writes. I’m grateful to him for teaching me more deeply about the generations who preceded us. His determination to search for truth is a great gift that he shares with all of us in this column. I value what he does, and I know other readers do, too.