Since the first flicker of film, book adaptations have served as one of the driving forces of the movie industry. As early as 1896, nascent filmmakers were shooting individual scenes from books by Charles Dickens, George du Maurier and others. Thomas Edison’s Edison Studios made a version of Frankenstein in 1910. Since that time, characters like Frankenstein, Dracula, and Sherlock Holmes have hit the screen dozens, even hundreds, of times. In recent decades, we’ve seen multiple takes on single books by Stephen King and no shortage of interpretations of Spider-Man and Batman. Yet among all of these towering characters of culture is an autobiographical family story about efficiency experts that keeps coming back. That’s Cheaper by the Dozen, and it just got remade again.

Frank Bunker Gilbreth liked figuring out the best way to do a job. Born in 1868, he lost his father young and opted to work instead of pursuing college. Finding his way into building trades, Gilbreth noticed how workers like individual bricklayers tended to approach the same job differently. For the next several years, he threw himself into learning every construction job he could and went to night school for mechanical drawing. He started inventing and patenting ways to make construction easier, like a scaffold to hold bricks. He also patented the “Gilbreth waterproof cellar,” an early attempt to prevent leaks in basements.

Gilbreth starting his own construction company and became a significant builder in the U.S., erecting everything from factories to dams. He trained laborers to do jobs the same way in a pursuit of making things more efficient. His “one best way” to do every job approach led to Gilbreth studying motions; he would try to break down manual labor into the most efficient series of motions that you could repeat to finish a task. Later, during World War I, Gilbreth served as a major, and he developed a rapid system for soldiers to disassemble and reassemble rifles. The basics of this method are still used in the modern military, as is Gilbreth’s notion that surgeons should have an assistant (he called them “caddies”) to hand them instruments during operations so that the surgeon could continue his focus on the patient.

Gilbreth married Lillian Evelyn Moller in 1904. They started having children in 1905; between 1905 and 1922, the Gilbreths had twelve kids. By 1912, Gilbreth chose to wind down his construction operations and focus full-time on being an efficiency expert. Lillian joined him in the vocation, and they studied work processes across a variety of fields. The Gilbreths published their first book, Bricklaying System, in 1909, but they initially kept Lillian’s name off; the couple figured that her lack of a PhD might make people doubt their expertise. Lillian did earn that PhD, and became a credited co-author with their fifth book.

The Gilbreths, faced with their large and growing family, decided to apply efficiency techniques at home. The couple workshopped ideas with the kids, figuring out the best way to get everyone fed, washed, dressed, and out of the house. Frank even tried to deduce the most efficient number of moves in took to wash your entire body in the bath. Frank died in 1924, but Lillian lived and worked until 1972. Turning away from the sexism she found in engineering, Lillian recentered on projects like home design. She invented and patented a number of things that we take for granted now, like light switches on the wall, shelves inside refrigerators (notably the egg keeper and butter tray), and the foot-pedal trashcan. Lillian also argued for counters to be of uniform height and for the room’s layout to make a “kitchen triangle,” facilitating the move from prep to stove to sink in the smallest number of steps. Lillian continued to write about labor, management, techniques to help amputees in the workplace, and more until she passed.

The Gilbreths’ story might have faded to only being well-known in the efficiency field if it hadn’t been for two of their children. Frank, Jr. was editor of the school paper at the University of Michigan and fought in the Navy in World War II, earning a bronze star and two air medals. After the war, he went into the newspaper business. His sister Ernestine was already writing a book based on anecdotes and experiences that the large number of kids had living in an efficiency-obsessed household. Lillian recommended that Frank, Jr. take a look at it, and he and Ernestine completed it together.

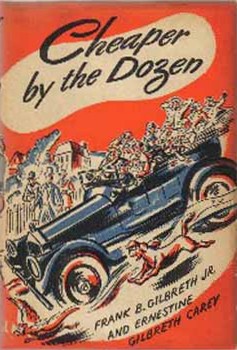

Cheaper by the Dozen was a hit on arrival in 1948. It won the French International Humor Award and was quickly adapted into a film in 1950. The success led Ernestine and Frank, Jr. to write a sequel, Belles on Their Toes, that same year; in 1952, it also made it to the screen. The sibling authors shared all of their profits evenly with Lillian and the rest of their brothers and sisters, feeling it was only right since they’d adapted all of their lives. The pair continued separate literary careers after the first two books, while Cheaper and its sequel would continue to sell around the world.

The film adaption was a positively reviewed success. Clifton Webb and Myrna Loy turned out noted performances as Frank, Sr. and Lillian. The film ends with Frank, Sr.’s passing, and explains that Lillian would go on to be a leader in efficiency. Loy returned for Belles on Their Toes, as did many of the young actors playing the kids. The film doubled its budget, but wasn’t a major hit. The first film ran frequently on various cable and syndication packages in the years afterward, and is presently available to watch on Prime Video and other outlets.

In the ’60s through the ’90s, the “Wow, that’s a lot of kids” genre yielded the Gilbreths’ place to the real-life Beardsleys and the fictional Bradys. The Beardsleys were a blended family that inspired the film and TV series Yours, Mine, and Ours. Though not a direct adaptation, the blended family concept influenced the creation of The Brady Bunch; the show has never really gone away with spin-offs, an adult drama version, hit film adaptations, and, yes, even a renovation reality show continuing to this day. (We’ll save the variety show for “TV’s Worst: Variety Show Edition” somewhere down the line.) The Gilbreths’ tale did emerge as a stage play in 1992 by Christopher Sergel; Sergel then turned the play into a stage musical.

Cheaper by the Dozen (2003) trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Trailer World)

However, in 2003, the Gilbreth story came back to the screen with a twist in a new Cheaper by the Dozen. Directed by Shawn Levy (who has gone on to fame for directing the Night at the Museum series, producing the Oscar-nominated Arrival and Netflix hit Stranger Things, and collaborating with Ryan Reynolds on movies like Free Guy, The Adam Project, and the upcoming Deadpool 3), this version stars Steve Martin and Bonnie Hunt. The family has been renamed the Bakers (heh; Baker’s dozen), although Hunt’s Kate has Gilbreth as her maiden name. In this take, Tom (Martin) is a football coach, and Kate is the author and efficiency expert. The movie was a big hit for 20th Century Fox, pulling in just under $200 million. A sequel (Cheaper by the Dozen 2) followed in 2005 to decent box office, but savage reviews.

Cheaper by the Dozen (2022) trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Walt Disney Studios)

After Disney completed its acquisition of Fox in 2019, then-CEO Bob Iger noted that a new version of Cheaper by the Dozen would be happening sooner rather than later, and that it would be targeted for the studio’s streaming service, Disney+. The film arrived on March 18 with a new series of twists. Gone is any real connection to the Gilbreth story; the family name, Baker, comes from the 2003 version. The film focuses largely on the concept of multi-ethnic blended families, with parents Paul (Zach Braff) and Zoey (Gabrielle Union) overseeing a family that includes kids from their previous marriages, their own two sets of twins, an adopted son, and Paul’s nephew. It’s a modern story about the kids’ social challenges and how Paul, Zoey, and their exes manage time and attention for their kids.

While there is little connection to the original story in the new film other than a brand name, it does lead one to ask the question: why do audiences seem to like shows about huge families? That’s obviously become a reality show staple, and other long-running series like Parenthood (also inspired by a Steve Martin film) have dealt with wide-ranging family issues. Maybe these kinds of stories are comforting when viewers see all the challenges the parents have to go through (one could imagine someone saying, “Look at them! We only have four, and that’s crazy enough!”). While the versions of the films and their concerns are different, there is one common thread: From the original to the new one, the suggestion to the audience is, simply, you can get through this. If this family can get a dozen kids up and fed and off to school, maybe it gives hope to the people just trying to get two out of the door. Whatever the case, it’s likely that we haven’t seen the last of the Gilbreths, or the Bakers, or whomever the next dozen turns out to be.

Featured image: ©Walt Disney Pictures; ©20th Century Studios; ©20th Century Studios; All images Fair use

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now