Our fathers never knew one another, nor had they ever met. But in the end, at the end of their lives, that is, the sickness they shared betrayed them in a like manner, over a plate of food. Kelly’s dad, Quent, had a meltdown in a Mexican restaurant with a taco. My old man, Marty, flipped his wig when my mother served banana pudding for dessert one evening.

I don’t even know what a taco is! Kelly’s father sneered.

Bananas! My father bellowed, recoiling from his plate. I hate bananas! Everybody knows I hate bananas!

These incidents took place 20 years and 200 miles apart. My father’s at home, at the dinner table, on a Saturday night in Santa Fe. Quent’s this afternoon, in a restaurant in Salida, where we’d stopped for lunch after a drive in the mountains.

Kelly hadn’t witnessed my old man’s mental collapse. She and I didn’t even know one another at the time. But me, I’d had a front row seat to her father’s breakdown, and the memories it stirred left me sick at heart.

Quent was in the hospital tonight, under observation. We’d driven him to the emergency room ourselves. Neither Kelly nor I knew what would happen when they released him tomorrow morning except, of course, that it wouldn’t be pleasant. Not for any of us, but especially not for Quent.

The incident in Salida had changed things. Clarified them, you might say. Quent had arrived at a grim intersection in his life, and it was clear he would have to live under someone else’s care from now on.

We’re stuck, Kelly said. Aren’t we? We’re stuck between a rock and hard place.

I didn’t know what to say, so I said nothing.

Like me, Kelly had begun to understand the bigger picture, the connection between today’s insanity and the hundreds of other small, unhinged deeds her father had acted out over the past nine months.

He can’t live alone anymore, can he?

Neither of us had used the word crazy at this point. Her dad’s only sin was that he was an old man — a sick old man — and you couldn’t fault a sick old man for falling off his rocker, could you? On the other hand, you couldn’t go around pretending he was normal, either. That would only invite disaster.

Kelly said, Is this how it was with your father, Seth?

I told her it was.

She’d known about the Big Banana Blow-up for some time. But what she didn’t know was that after committing my father to that veterans home in Tucson, I never laid eyes on him again. He parted this world alone, a stranger even to himself.

I put my arm around Kelly’s shoulder, squeezing it for reassurance. My own reassurance, as much as hers. I was 17 years her senior, a “cradle robber” our friends used to joke. But those words had lost all their humor as I grew older, and today, after everything we’d been through, the term robber seemed an honest description of what I’d become. I’d tried to cheat time with a younger woman, a trophy wife. I’d wallowed in sins of vanity and arrogance. Crimes of pride and passion.

On my last birthday (my 57th), while we were having drinks with a couple from Kelly’s workplace — Paul and Prentiss Ogden — Kelly looked across the table and declared half-jokingly she had no intention of giving up her career to play nursemaid to an old man on the doorstep of retirement. She loved the arts too much, she said. She loved the activity, the self-validation, the bohemian lifestyle. She wanted to work abroad someday, curating her own exhibits. Mentoring young artists. Opening doors for the disadvantaged and downtrodden. She was ready to embrace whatever came along in this life, she said, dishing me a wicked little smile, so long as it wasn’t the death trap of geriatric domesticity.

The Ogdens were newly married. Fresh-faced and brimming with idealism. You could see them hanging on Kelly’s every word, admiring her every observation as if she’d spent her youth in the company of the Muses, sipping from the Pierian Spring.

What about you, Seth? Paul Ogden asked, propping his arm on the table and presenting me with a hearty smile. What’re your plans once you hang up your spurs?

I smiled back. My plan is to be a bum.

Ogden laughed, politely.

A useful bum, I added, nodding at Kelly. I don’t want Miss Ambitious here to cast me into the streets for lack of purpose.

Kelly raised her wine glass and gestured at my birthday cake. The candles I was about to blow out had burned halfway down while the four of us were gabbing. Better hurry and make your wish Funny Man, she said. You’re not getting any younger, you know.

* * *

When we settled into bed that night, Kelly told me I was lucky. You had your mom to look after your dad when he got sick, she said. My dad only has me.

I winced a little. If you wanted to say I was lucky not having to look after my old man while my mother was alive, by all means say it. Because I was lucky. I didn’t have to witness the rotting of his mind, or the wasting away of his body the way she had. But luck can be an unreliable companion, even at its best, and in the end, the disease that killed my father destroyed my mother, too, by proxy, and that was something I hadn’t expected.

Kelly took a deep breath, rolled onto her back, and stared at the ceiling. That man in the hospital isn’t my dad, she said in a small, defensive voice. He looks like my dad, but he isn’t. The man we brought back with us from Salida this afternoon isn’t my father.

That was all she said.

You’re a good daughter, I whispered. Yet as I muttered those empty words, I could only think of how fortunate we were to be alive after Quent’s outrageous and unexpected behavior.

What is this? he’d demanded, staring at the waitress when she set down his lunch plate.

It’s a taco, Dad, Kelly said politely, touching his arm.

Quent looked at the dish with disdain, blood rising in his cheeks. A taco! He yowled, painfully, drawing the eyes of everyone in the restaurant. I don’t even know what a taco is!

Kelly and I exchanged a nervous glance. It was clear that the meal, not yet begun, was already over. Downplaying her father’s outburst, she laid her napkin aside and gathered her jacket. Pay the bill, why don’t you, Seth, she said, pushing her chair out from the table. Dad and I will meet you at the car.

Quent battled us all the way down the mountain, raging at every switchback on the highway. Panicking at every twist in the road.

You took the wrong turn! he shouted as we started down Monarch Pass. You took the wrong goddamned turn! He lurched forward, gripping the seatback, swiping at the wheel. What are you people doing to me!

Kelly snatched his hand and squeezed it, assuring him everything was all right. But he refused to listen, and in the mayhem that followed he tried to jump out of the car.

I’d never wrestled with an old man before. I’d heard it said crazy people can sometimes possess the strength of many men, and in Quent’s case it was true. I had to pull off onto a runaway truck ramp and grapple with him in the back seat until we were both sweating and out of breath. Kelly stared at us with outsized eyes. Aghast. We could have ended up in a flaming crash at the bottom of the ravine if things had gone any worse. But our luck, what we thought of as luck, held out.

I managed to buckle Quent in while Kelly leaned over the seat, soothing him. But even with his shoulder harness and lap belt tightly in place, we didn’t take chances. I switched on the childproof door locks, and kept one eye fixed on the rearview the rest of the way home, making certain he didn’t break free.

* * *

It was almost midnight, but we were still awake.

What do you think? Kelly said.

I glanced at the half-shadow of her face, pale in the moonlight coming through the bedroom window. There was no good answer. We both knew this, but just the same we each hoped the other might find something positive to say.

I think we did the best we could, I told her, though nothing about the day felt victorious.

That’s not what I meant, she said.

I knew what she meant, but I kept my opinion to myself.

We’ll have to put him somewhere, won’t we?

We should have quit talking and made love. In the old days, that’s how we would have handled a situation like this, this wretched turn of events whose only possible outcome was heartbreak. We would have defied it. Outlasted it by insisting it had no sway over us. But we were too grown up, too responsible for that sort of reckless passion anymore. So instead of losing ourselves in one another’s arms, we pulled up the blankets and retreated into silence.

I remembered the evening of my father’s crack-up. It was just before Thanksgiving, on a Saturday night. Mom had decorated the table with a festive centerpiece — an armada of pinecones and gourds and floating candles — and uncorked a bottle of good Beaujolais to serve with her roast chicken.

I have many memories of that night, but the coldest of them is a snapshot of my old man staring at his pudding, face changing moment by moment as if a bank of clouds were passing overhead. The sight of the dessert had triggered something in him, bringing out a look in his eyes that sharpened and released in a flashing rage. He glared at the pudding with contempt, and in a moment of distilled vitriol, erupted. He hated bananas! Loathed them! My mother, whom he’d once trusted, had betrayed him in the most foul and insidious way! I hate bananas! he screamed, pounding his fists on the table. You can take your bananas and … and …

My old man had never uttered the F-word in his life. He could be quick tempered, yes, and easy to anger if pushed too far, but vulgarity was never his default medium. He was old-school Catholic with old-school manners, and there was no way in the world he would have uttered such a hopeless comment had he not been out of his mind.

Seth?

Yes.

We’ll have to put him in one of those places, won’t we?

* * *

We visited a number of nursing facilities that weekend, all of them disappointing in one way or another. But we had to choose, so we chose, understanding (without saying so) that the decision would make no difference whatsoever to Quent. It was ourselves we were trying to save now, our own sanity, not his.

The place we landed on was called Arcadia Gardens. Mrs. Barnes, its director, gave us a full tour of the grounds. The rooms were pastel and pleasantly appointed, the windows tall and sunny. It boasted both recreation and entertainment centers, and the social calendar promised a brow-raising variety of festivities — weekly excursions, in-house concerts, and holiday programs Quent would be certain to enjoy. There were no actual gardens at Arcadia Gardens, not that we saw. But the entire facility smelled of plug-in fragrances, and if you couldn’t have real flowers or appreciate the difference, it probably didn’t matter.

The tour lasted two hours. The staff was so cheerful and attentive it made the betrayal we were about to commit seem not only cruel and uncaring, but shamefully underhanded. It would have been better all around, I think, if we had forgone the orientation and simply admitted what we both knew — that we were abandoning Quent to a lonely and desperate end — only we weren’t ready, yet, for such desperate declarations of honesty.

When we got to the dining room, Mrs. Barnes paused. Eating, she said in a wholesomely plagiaristic voice, was a small good thing in a place like this. I stopped and blinked, but she looked away when our eyes met. She led us to the kitchen where she introduced us to the staff. The chef and nutritionist. Even the baker. There was a long discussion about the holistic rewards of healthy meals, and Kelly and I nodded our agreement, assuring her there was no need to sell us any further. We were pleased with the arrangements, we lied. We were prepared to sign the paperwork.

Mrs. Barnes continued talking, propelled by sugary aphorisms plucked straight from the Arcadia Gardens’ four-color brochure. Old wood burned brightest, she said. Old wine was best to drink. Old friends were gifts to be treasured. Glimpsing past my shoulder, she raised her small white hand and called out a greeting to a wrinkled old man shuffling toward the television room. He looked up, not startled exactly, but surprised.

Hello, Rudy? Mrs. Barnes waved. Rudy, do you have a moment?

Rudy looked at us, dully.

Rudy, this is Mr. and Mrs. Farber. They’re wondering about the food here. Can you tell them something about the food?

Rudy, who was wearing a bathrobe and slippers, blinked wisely, scratched at his head of unkempt silver hair, and said in a thoughtful voice, Pile, pile, glop.

* * *

Two weeks after consigning the rights to what was left of Quent’s ever-graying gray matter to the caregivers at Arcadia Gardens, I bumped into a woman outside the grocery store near our home. I was walking in and she was on her way out, and an awkward collision ensued (my fault entirely) in which we found ourselves tangled in one another’s arms.

The woman lurched back as I blundered into her, and the sack of groceries she was carrying fell to the ground, breaking open on the pavement. Fruits and vegetables tumbled in all directions.

I gasped, mortified, and stuttered an apology. I was so sorry! I’d had my head down! I wasn’t paying attention!

The woman was young, Kelly’s age, and pretty. The print dress she wore flattered her bare legs. She smiled, embarrassed, as I bent to chase the runaway produce. Please, she begged, it’s all right. Don’t worry about it.

I’m so sorry, I said again. Look at the mess I’ve made!

A boy in a red apron with tattooed arms hurried to our side. He had been wrangling grocery carts in the parking lot, and abandoned them when he saw the havoc I’d created. No worries, he said, stooping to help. No worries at all.

I held up a vegetable, the name of which escaped me, and tried to hand it to him. It was what? A parsnip? Rutabaga? I’d lost the word in all the hubbub. I knew it didn’t matter what it was called, that in the midst of the chaos I’d created no one cared but me. Yet as I knelt there, fumbling with the thing, trying to extricate myself from the trouble I’d caused, the misplacement of the term bothered me.

We’re good, sir, the boy said, rising to his feet with the bundle of loose produce bulging in his inked-up arms. I’ve got this. He plucked the rutabaga from my fingers — that was it, rutabaga! — and turned, casually, to the woman. Come with me, ma’am, he said with a slight tilt of his head. I’ll have the manager replace what’s damaged.

The young woman hesitated. She could see what the boy couldn’t. She reached down and helped me, awkwardly, to my feet.

When I got home that afternoon, empty-handed and embarrassed, I drove the car into the garage and sat in the dark with the door closed.

Kelly was out back, working in the garden. She wandered into the house a little while later with red-rimmed eyes, runnels of dirt cutting a crooked path down her cheeks.

She put her arms around me and wept. At first I thought I’d been found out, that someone, one of our neighbors, had seen me at the grocery store. But it wasn’t that at all. It wasn’t about the groceries, or the dinner I’d failed to prepare. It was about something else altogether, something we’d come to see in ourselves and hadn’t yet found a way to understand.

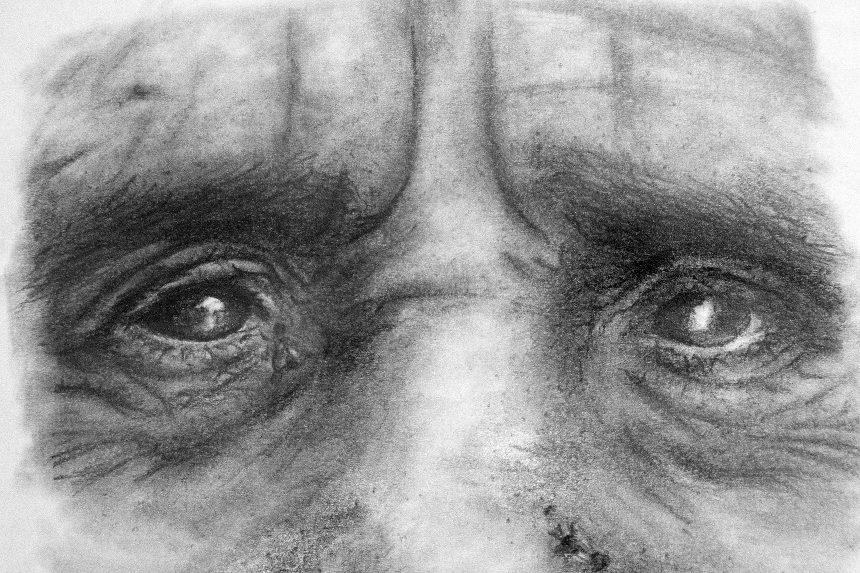

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

So sweet and sad. Lovely writing.

I have loved Robert’s writing for many years. So good to see him here in the Saturday Evening Post for many more to discover him.

My father died a few years ago with dementia. I imagine he felt much as the narrator of this story does: facing his own frightening demise, and helpless to stop it. And the author nailed the ending. And earnest, healtfelt, lovely piece of writing.