This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

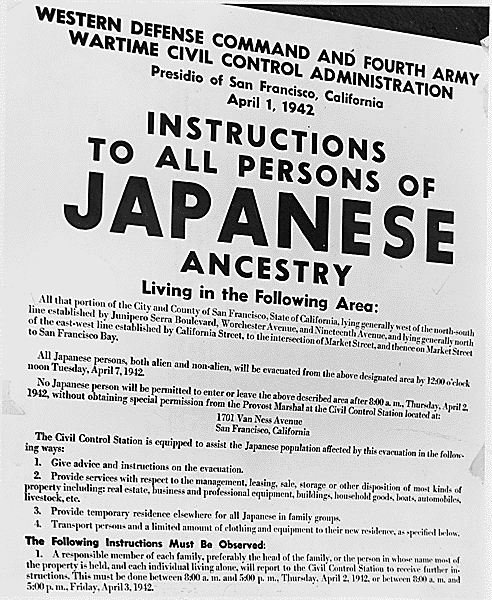

On May 3rd, 1942, General John DeWitt, the military officer in charge of the Roosevelt Administration’s unfolding plan for Japanese American incarceration, issued an infamous broadside ordering “all persons of Japanese ancestry” in California to report to the authorities. The proclamation illustrates not just the authoritarian machinations of the incarceration program, but its purposefully destructive details; for example, Japanese Americans were ordered to bring only “that which can be carried by the individual or family group,” a proscription that led to most of the incarcerated families losing their homes, property, and livelihoods.

The 80th anniversary of this painful document, as well as the start of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, is an opportunity to remember Japanese incarceration and those who resisted and challenged it. At the top of that list is Fred Korematsu, the young man who gave his name to the Supreme Court decision that upheld incarceration as constitutional. Yet Korematsu’s battle, influence, and legacy go far beyond that individual legal loss.

Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu (1919–2005) had just turned 23 when Executive Order 9066 was enacted. Korematsu had been born and raised in Oakland, to parents who had immigrated from Japan in 1905. Much of his early biography reads like that of any other American child and teenager: he attended Oakland public schools and was on the tennis and swim teams at Castlemont High School; he worked at the family business, a flower nursey in San Leandro; he dated a classmate, Ida Boitano. But those same experiences were marred by anti-Japanese prejudice: Boitano’s Italian American family disapproved of their relationship, believing the Japanese to be an inferior race; when military recruiters visited Castlemont High they told Korematsu, “We have orders not to accept you,” and refused to give him promotional materials; and he was summarily fired from his first two jobs after high school due to his Japanese heritage.

These formative experiences helped prepare him to resist discriminatory policies like Japanese incarceration. And so when the May 3 broadside was issued, Korematsu took immediate action. He went into hiding with his girlfriend, underwent facial plastic surgery in order to repair an identifying broken nose and (as he later told investigators) more broadly “change my appearance so that I would not be subject to ostracism when my girl and I went east,” and sought to redefine his heritage as mixed Spanish and Hawaiian. But on May 30, police apprehended Korematsu on a street corner in San Leandro, and he was arrested and held in prison in San Francisco pending his transfer to an incarceration camp.

Korematsu’s initial resistance to incarceration was driven far more by his personal life and goals than by any broader civil rights agenda. He did however believe in a legal and philosophical principle underlying his resistance, the idea that “people should have a fair trial and a chance to defend their loyalty at court in a democratic way, because in this situation, people were placed in imprisonment without any fair trial.” And when his case began to receive national media attention, Korematsu would be given the chance to serve as a representative for such principles and for Japanese American resistance to incarceration.

While he was in prison, Korematsu was contacted by Ernest Besig, founder and first director of the ACLU’s northern California branch, about whether he would be willing to become a test case for legal resistance to incarceration. Besig was out on a limb in taking this position, as both a poll of northern California ACLU members and the organization’s national office opposed these efforts to contest the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066. But Besig wrote to the ACLU executive director Roger Baldwin that “we feel compelled to proceed as before, because we cannot in good conscience withdraw from the case at this late date.” Perhaps encouraged by this support, Korematsu agreed to serve as Besig’s test case, and Besig (not himself a lawyer) recruited a friend, the fiery San Francisco attorney Wayne Collins, to represent Korematsu in his legal challenge.

Collins was perhaps more gifted as an orator than an attorney, and Korematsu lost his case at each judicial level. In September 1942, San Francisco federal judge Adolphus St. Sure found him guilty and sentenced him to five years’ probation (although St. Sure seems to have done so reluctantly, as he initially refused to issue an order remanding Korematsu into military custody). After that initial guilty verdict, Korematsu was removed to the Central Utah War Relocation Center in Topaz, Utah, where he would remain for the duration of the war. A U.S. Court of Appeals agreed to hear his appeal in March 1943, but upheld the original verdict in a January 1944 decision.

The U.S. Supreme Court heard the case in Korematsu v. United States in March 1944, but in December ruled 6–3 that compulsory exclusion was justified during circumstances of “emergency and peril.” In his arguments before the Supreme Court, Collins demonstrated his rhetorical flair, arguing that “the only act resembling [internment] was committed by Adolf Hitler, who penalized German citizens on the basis of their nationality.” He convinced the three dissenters, as illustrated by Justice Owen Roberts’s description of “the case [as] convicting a citizen as a punishment for not submitting to imprisonment in a concentration camp, based on his ancestry, and solely because of his ancestry.” But the majority sided with the idea that such racial and national exclusions were temporarily necessary in wartime.

While Korematsu did not win his legal battle nor escape from incarceration, his resistance was an inspiring and influential one on multiple levels. Most immediately, it seems to have had a direct impact on another December 1944 Supreme Court decision that went the other way and helped limit and eventually end incarceration. Collins also represented that plaintiff, Mitsuye Endo, a 22-year old clerical worker who had filed a writ of habeas corpus to oppose her indefinite incarceration at the Tule Lake (California) camp and whose case was heard immediately after Korematsu’s. In Justice Hugo Black’s majority opinion in Korematsu he overtly cites Ex parte Mitsuye Endo, arguing that “the Endo case graphically illustrates the difference between the validity of an order to exclude and the validity of a detention order after exclusion has been effected.” While the Court’s threading of the needle between a valid arrest and an invalid indefinite detention unfortunately did not help Korematsu’s individual case, it quite possibly would not have been heard at all if Korematsu had not been pursuing that case.

Not at all coincidentally, the Court released its unanimous decision in support of Endo’s writ on the same day (December 18, 1944) it did Korematsu. Writing for the Court in Endo, Justice William Douglas notes that “We are of the view that Mitsuye Endo should be given her liberty,” adding, “whatever power the War Relocation Authority may have to detail other classes of citizens, it has no authority to subject citizens who are concededly loyal to its leave procedure.” The Endo decision represented a significant step in opposing incarceration, indeed beginning the process of release for many incarcerated Japanese Americans, and Korematsu’s case clearly factored into it.

For a few decades after his release from the Topaz camp, Korematsu disappeared into the private life he had long desired. Although he continued to face anti-Japanese prejudice, he moved to Detroit, married Kathryn Pearson in October 1946, moved back to Oakland with her when his mother became ill in 1949, and had two children over the next few years.

Korematsu found himself back in the public conversation in the early 1980s when Peter Irons, a lawyer and professor at the University of California, San Diego, persuaded Korematsu to testify in a proceeding that could vacate his original conviction. Irons had been researching a book on incarceration and discovered evidence that the U.S. solicitor general who argued Korematsu before the Supreme Court had withheld FBI and military reports, which concluded that Japanese Americans posed no security risk. Irons brought a writ of error before San Francisco federal court judge Marilyn Hall Patel, and Korematsu testified eloquently, arguing that “I would like to see the government admit that they were wrong and do something about it so this will never happen again to any American citizen of any race, creed, or color,” and adding, “If anyone should do any pardoning, I should be the one pardoning the government for what they did to the Japanese-American people.” On April 19, 1984, Patel formally vacated Korematsu’s conviction, an important legal step that helped pave the way for future victories including the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which provided financial reparations for each surviving detainee.

In the last years of Korematu’s life he took his public activism one step further. After the

September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, Korematsu became an outspoken advocate for civil liberties and critic of many of the War on Terror’s infringements of such rights. In particular, he filed two amicus curiae briefs to accompany Supreme Court cases involving detainees at the Guantanamo Bay prison: an October 2003 brief for the cases of Shafiq Rasul and Khaled Al Odah, in which Korematsu cites numerous historical examples (including but not limited to Japanese incarceration) to argue that the restriction of civil liberties is never justified; and an April 2004 brief for Jose Padilla’s case, in which Korematsu parallels his own incarceration situation to that of Padilla and argues, “full vindication for the Japanese-Americans will arrive only when we learn that, even in times of crisis, we must guard against prejudice and keep uppermost our commitment to law and justice.”

We’re in another time of crisis, with many of our civil rights and the core elements of our democracy under consistent attack, and that commitment is being tested once more. In such moments it’s vital that we remember Japanese incarceration, when our collective ideals have so thoroughly failed in the face of fear and bigotry. And when we do, we can likewise commemorate the legacies of inspiring Americans like Fred Korematsu and other like him who fight for a just and inclusive America.

Featured image: Fred Korematsu and family (courtesy of the family of Fred T. Korematsu, Wikimedia Commons via the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now