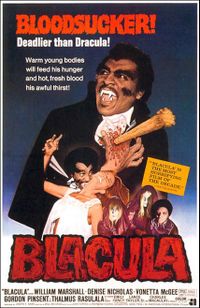

Any horror fan worth their salt will tell you that the genre shouldn’t just be confined to the month of October. That’s particularly true of horror films, which have had major hits open in every season of the year for decades. In one particular late summer week fifty years ago, a strikingly different horror movie hit screens. It kicked open a door for a new vision of who belonged in horror films. That movie was Blacula.

“Theme from Shaft” (Uploaded to YouTube by Isaac Hayes)

Blacula rode the wave of Blaxploitation cinema that had kicked off with Cotton Comes to Harlem in 1970 and began to boom with Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song and Shaft in 1971. “Blaxploitation” as a term arose from comments made by Junius Griffin; as president of the NAACP branch based in Beverly Hills-Hollywood, he remarked that this new wave of films perpetuated negative images due in part to their immersion in crime-centered storylines and the use of stereotypical characters. The counterargument from the filmmakers behind them was that they were re-centering the narrative with Black leads and Black creative talent on both sides of the camera. The films found an audience, particularly Shaft, which was a big success for MGM and won an Academy Award for Best Song for Isaac Hayes’s “Theme from Shaft.” That breakthrough encouraged other stories to jump on the trend.

American International Pictures had already been established as a purveyor of low-budget films, especially those targeted at teen audiences. They often found success within the horror genre, notably working with low-budget film legend Roger Corman. Into this environment came Blacula. Director William Crain and leading actor William Marshall were both Black men, a fact that would resonate; as Dr. Robin R. Means Coleman puts it in the Shudder documentary Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror, which was based on her book, Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present, “And so here’s where you see how knowledgeable Black directors and actors can have an extraordinary impact on a film.” Director Tina Mabry also explained in the documentary, “That created kind of a cultural shift.”

The trailer for Blacula (Uploaded to YouTube by Shout! Factory)

Crain initially struggled with the idea of directing the film. It first came to his attention under the original name for the script, Count Brown’s in Town. He told The Daily Beast, “When I read the script, I kind of put it down. My parents said to me, ‘If you have the chance to do this movie, you need to go do it—do the best you can.’” He took their advice.

The resulting film was notable for a number of reasons. Apart from playing the first Black vampire on film, Marshall brought a combination of regal bearing, suave intelligence, and simmering menace to the role of the African Prince Mamuwalde, who was transformed into a vampire by Dracula in the 1700s. Crain consciously evoked elements of African culture in the 1700s-set scenes and used modern trappings like funk music by The Hues Corporation in the contemporary portions.

Juanita Wakes Up! from Blacula (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

During production, Crain lobbied regularly for a high-speed (that is, slow-motion) camera for one particular shot. AIP finally came through with it after realizing that Crain was making something memorable when they saw early scenes from the film. With that camera, he created one of the most memorable scenes in the film: Juanita, a female vampire charging to attack, which remains frightening to this day.

Blacula turned out to be very successful for AIP. It did well at the box office and won a Saturn Award for Best Picture. The next year, AIP greenlit a sequel. Marshall was paired with the iconic Pam Grier for Scream, Blacula, Scream, a film that’s been praised for centering a female protagonist against the title villain. Though the film didn’t make as much money as its predecessor, it was praise by the likes of critic Gene Siskel and Kevin Thomas of the L.A. Times.

The trailer for Blade (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

The broader effect of Blacula is that it helped trigger a wave of Black-centered horror films. These included Ganja & Hess, Abby, and Sugar Hill in the short term while offering inspiration to later offerings like Candyman, Tales from the Hood, and Bones. The character of Blacula and the era of Blaxploitation action heroes certainly influenced the creation of Blade at Marvel Comics; writer Marv Wolfman and artist Gene Colan introduced the vampire hunter in The Tomb of Dracula #10 in 1973, and the character’s eventual big-screen adaptation in 1998 proved the viability of Marvel characters at the movies. Modern filmmakers like Jordan Peele (director of Get Out, Us, and Nope) acknowledge that all the advancements made since the 1970s have paved the way for today’s climate, which is far more friendly to horror material from Black creatives. Considering the massive success of Peele, the recent rebirth of the Tales from the Hood and Candyman franchises, and a greater inclusion of Black leads (as in Beast and The Invitation), the legacy of Blacula, much like its main character, will never die.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now