This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

In recent weeks, railroad workers have retaken a prominent place in our national conversations over labor rights and collective action. Many of America’s first such national collective labor actions in the late 19th century centered on railroad workers and their unions, from the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 to the Pullman Strike of 1894. And despite all that has changed in the railroad industry and nation alike over the century-and-a-half since those influential early strikes, these 21st century debates have revealed that railroad workers continue to face extreme and exploitative conditions.

With the assistance of the Biden Administration’s Department of Labor, the railroad workers’ unions and management seem to have come to a deal that is agreeable to both sides and that would avert a potentially crippling national strike. However this particular labor conflict continues to play out, the moment offers an opportunity for a broader conversation about the multi-layered history of American railroad workers. The stories of Black railroad workers, for example, reflect how such communities have embodied both the possibilities and the limits of the American Dream.

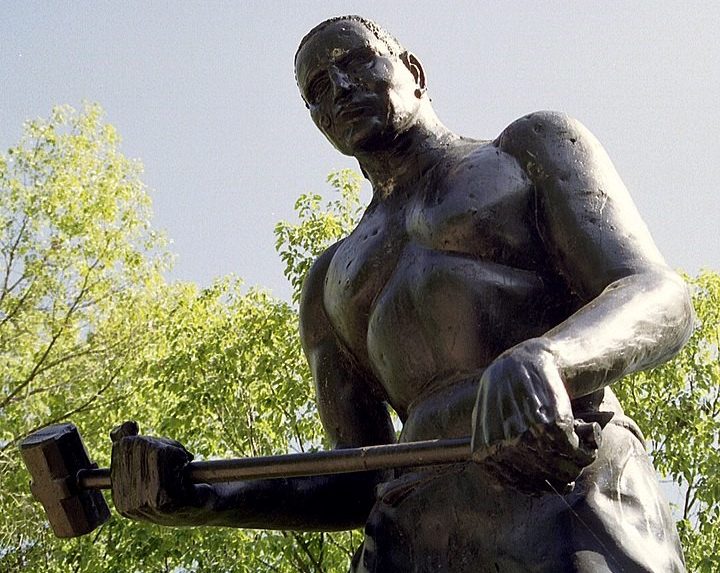

Two folk stories from the same late 19th century period as those first national strikes symbolize the Dream’s idealized myths and far more complex realities. One of the first uniquely American folk heroes was John Henry, the prodigiously strong and seemingly tireless African American railroad worker whose ability to outwork a machine in hammering out a tunnel became the source of countless folktales and songs. While the realities behind this folklore are ambiguous, historians have connected Henry’s story to early 1870s work on the Chesapeake & Ohio (C&O) Railway’s Big Bend Tunnel in Talcott, West Virginia — and have also discovered that Henry himself might well have been incarcerated during Reconstruction and leased by his warden to the C&O Railway.

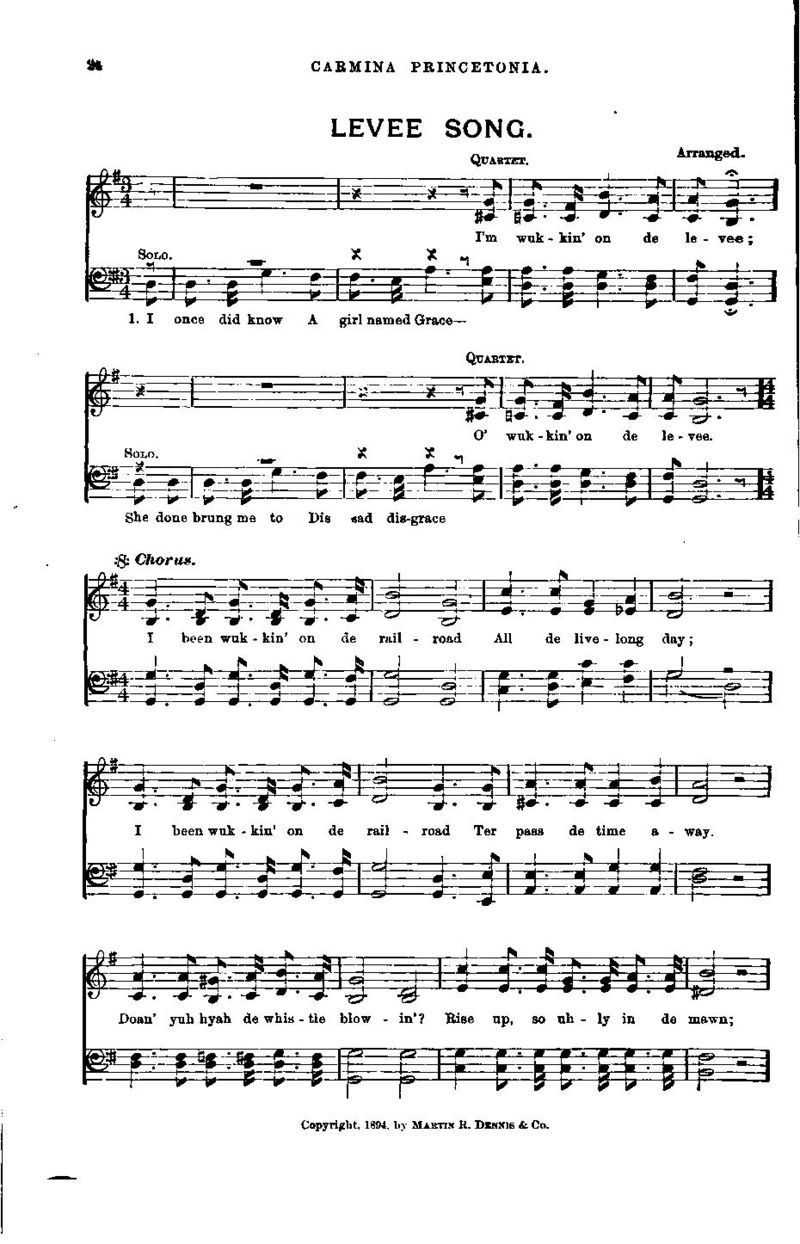

While Henry’s folklore overtly identifies his race as part of the story, another late 19th century folk text has become frustratingly disconnected from its complex cultural origins. The enduringly popular song “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad” originated with 1894’s “Levee Song,” a minstrel show text performed in a stereotypical dialect and featuring lines such as “Sing a song o’ the city/Roll dat cotton bale/N***** ain’t half so happy/As when he’s out of jail.” By the time the song was first recorded in the 1920s much of that section had been cut, but the verses that have been retained likewise connect to stereotypical representations of Black history, as in the character of “Dinah,” which was a common 19th century name for a symbolic enslaved woman. It’s possible that the unceasing and dreary work performed by the song’s speaker reflects labor and/or racial histories beyond these troublingly stereotyping and mythologized elements. But in any case a song still sung by countless schoolchildren needs to be better remembered in connection with these complex cultural contexts.

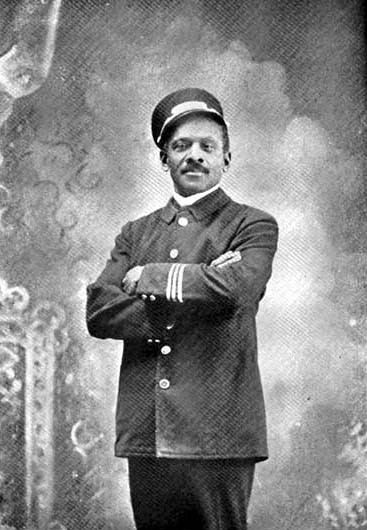

African American railroad workers performed a wide variety of railroad work, but beginning in the late 19th century and continuing for much of the 20th, one of the most common roles was that of Pullman porter. One particularly famous individual such porter, Nat Love, represents the links between the evolving role of the Pullman porter and images of the American Dream. Love had become famous as a former slave turned Black cowboy whose feats of riding, roping, and shooting had earned him the folkloric nickname Deadwood Dick.

But as he traces in his popular autobiography The Life and Adventures of Nat Love (1907), for the final stage of his iconic career Love went to work as a Pullman porter, helping many others experience and enjoy traveling the continent that had been so formative for him. The final few chapters of his book comprise an extended ode to both Pullman and America, culminating in lines like, “Then after taking such a trip you will say with me, ‘See America.’ I have seen a large part of America, and am still seeing it, but the life of a hundred years would be all too short to see our country America, I love thee, Sweet land of Liberty, home of the brave and the free.”

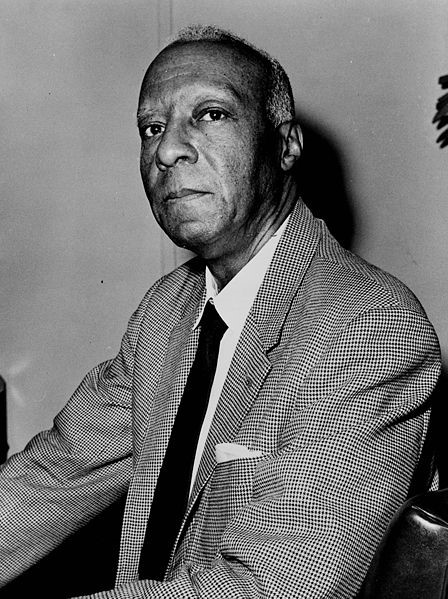

The collective experiences of Black Pullman porters were not as consistently idyllic as Love’s portrayal, however. We know that in significant part due to the multi-decade work and activism of A. Philip Randolph (1889-1979), the longtime labor leader, politician, and journalist who in 1925 was elected president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP). Across more than four decades of work in that role Randolph achieved countless victories for both that union, railroad workers more broadly, and all African Americans, making him not only a key figure in the history of the American labor movement but also an important influence on the developing Civil Rights Movement.

As 21st century railroad workers continue to highlight the gaps between the Dream and their lived experiences, helping lead the fight to make the Dream truly work for all Americans, we remember the role that Black railroad workers have consistently and centrally played in those stories.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now