Like many legends of the West, it’s hard to say exactly where the music genre we call Outlaw Country began. Some say that the name came from a particularly spirited night involving motorcycles on stage. Others say that it came from the fact that artists fighting for creative freedom from the Nashville establishment had, in effect, become country music’s outlaws. And while elements of truth may be found in any number of origin stories, there’s one irrefutable fact: Ladies Love Outlaws, released 50 years ago this month by Waylon Jennings, became a keystone text in the movement and solidified its law-breaking name.

Buddy Holly & The Crickets on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1957 (Uploaded to YouTube by The Ed Sullivan Show)

In 1972, Waylon Jennings was lucky to be alive. After starting out as a DJ and jingle singer, Jennings was recruited by Buddy Holly to play bass in his band on 1959’s Winter Dance Party Tour. Plagued by bus breakdowns and ill health among the participants, Holly decided to charter a four-seater plane to make the leg between Iowa and Minnesota on February 3. Rich Everitt recounted what happened next in his 2004 book, Falling Stars: Air Crashes That Filled Rock and Roll Heaven. Jennings decided to stick with the buses and gave his seat to J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson, who had the flu; likewise, Holly’s guitarist Tommy Allsup gave his seat to another name on the marquee, Ritchie Valens. Holly teased his band for not flying with him, saying that he hoped that their bus froze; Jennings jokingly told Holly that he hoped the plane crashed. That jest haunted Jennings for the rest of his life; the plane did crash, killing all aboard.

Waylon Jennings covered Roy Orbison’s “Crying” in 1962 (Uploaded to YouTube by Waylon Jennings)

Depsite the impact of the accident on Jennings, he solderied on in the music business. Jennings worked on his solo act of rock-leaning country and signed his first record contract in 1961. Though he worked within the establishment, Jennings was already gaining an outsider image with hard drinking and harder partying. By 1965, he’d made it to the Billboard Hot Country Chart and befriended another future outlaw, Willie Nelson.

Patsy Cline’s “Crazy,” as written by Wilile Nelson (Uploaded to YouTube by Patsy Cline)

Nelson had a start similar to Jennings, beginning in radio. During the ’50s, he started working as a singer-songwriter. He moved to Nashville in 1960. The following year, two songs that he wrote were turned into towering classics by other artists: “Crazy,” recorded by Patsy Cline, and “Hello Walls,” as done by Faron Young. “Hello Walls” spent 23 weeks atop the Country chart, while “Crazy” hit #2 and crossed over to the Pop Top Ten. By 1962, he was recording his own music.

Both Jennings and Nelson were finding success, but they both chafed at the Nashville system. Jennings liked recording with his own band, The Waylors, and rejected the notion of hired-gun studio musicians and lush orchestras backing watered-down fare. He liked to bring in his own producers and infused rockabilly and classic country and western elements into his work. Similarly, Nelson leaned away from the “Nashville Sound” and wove folk, jazz, and more into his tunes. He also gravitated toward the counterculture movement in Austin, growing out his hair.

The Eagles and Linda Ronstadt performing “Desperado” (Uploaded to YouTube by Eagles)

At the same time, mainstream rock had been undergoing a country infusion. Though everyone from Bob Dylan to The Flying Burrito Brothers had had some truck with it, the real avatars turned out to be The Eagles. Formed in 1971, the band would codify what many people considered “country rock” over the next few years with classic tunes like “Desperado.” The time was ripe with possibilities from audiences to embrace sounds coming from different, branching genres.

But by 1972, Jennings was in a bad place. He had struggled with hepatitis and was at a low point with his record label. Jennings even considered retirement. However, his drummer, Richie Albright, had other ideas; Albright encouraged Jennings to stick with it, and arranged a meeting with Neil Reshen. Reshen handled accounting and legal representation for some distinctly non-country acts like Miles Davis, Frank Zappa, and the Velvet Underground. Reshen was convinced that he could get the label to come to terms with Jennings; he also encouraged the musician to grow out his hair. Jennings hired Reshen as his manager, and the brash New Yorker’s fierce negotiations got Jennings everything he wanted: artistic freedom, covering all aspects of recording and producing the music right down to the cover art. Before long, Reshen would be hired by Willie Nelson to manage his affairs.

“Ladies Love Outlaws” by Waylon Jennings (Uploaded to YouTube by Waylon Jennings)

Ironically, Jennings wasn’t entirely happy with Ladies Love Outlaws. When RCA released the album in September of 1972, he still considered it a work in progress. Nevertheless, it hit #11 on the Country Album Chart and signaled that something new was brewing. A few critics noted the rock influence, with writers like Dean Tudor calling it “exciting.” Though Chet Flippo of Rolling Stone knocked the album, Jennings himself liked the review because he had the same criticisms about the record (notably that it was “unfinished”); Jennings took Flippo on tour with him. Despite occasionally mixed reviews, the album’s influence was immediate. The title track, a reference to Jennings’s relationship with his musician wife, Jessi Colter, would lend its name to the burgeoning movement of artists taking back artistic control. Before the record, they were just pains in the labels’ backsides. After the album dropped, they were Outlaws.

Kris Kristofferson’s “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” (Uploaded to YouTube by Kris Kristofferson)

In short order, a core of artists coalesced around the new concept. In addition to Jennings, Nelson, and Colter, singer-songwriter Kris Kristofferson became a major figure. Kristofferson was a true Renaissance Man; he was, in turn, a published essayist in The Atlantic; a NCAA athlete (football, track and field, rugby); a Rhodes scholar; and a helicopter pilot with the rank of captain in the U.S. Army all before he decided to split for Nashville and become a musician. By 1972, he’d already written classics like Janis Joplin’s “Me and Bobby McGee” (with Fred Foster) and Johnny Cash’s “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down.” His independent spirit and overall sensibilities fit right in with the gang.

“You Never Even Called Me By My Name” (Uploaded to YouTube by DavidAllanCoecom)

So did Tompall Glaser. As a solo artist and with his brothers (as Tompall & the Glaser Brothers), he had been in the business since the 1950s. Glaser shared bills with Patsy Cline and had a recording studio that everyone called Hillbilly Central. That studio would become a hub and home base to Outlaw artists. Jennings, Nelson, Colter, and Glaser generated a new burst of popularity and productivity with the Outlaw ethos. Other artists, like David Allan Coe, who had already cultivated an iconoclastic image, were recognized as being in the orbit of Outlaw, even if they weren’t part of the core group.

“Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way” (Uploaded to YouTube by Waylon Jennings)

Jennings directly addressed the feelings of many musicians and country fans with his 1975 song, “Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way.” The rock-edged tune bemoaned the “rhinestone suits” of the Nashville image and celebrated the music of pioneer performer Hank Williams, Sr. It’s perhaps no surprise that Hank Williams, Jr. would soon be viewed as, at the very least, Outlaw adjacent, for cultivating an image that included a rock-forward tunes, a full beard, and the perpetual wearing of sunglasses.

“Mammas, Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys” (Uploaded to YouTube by Waylon Jennings)

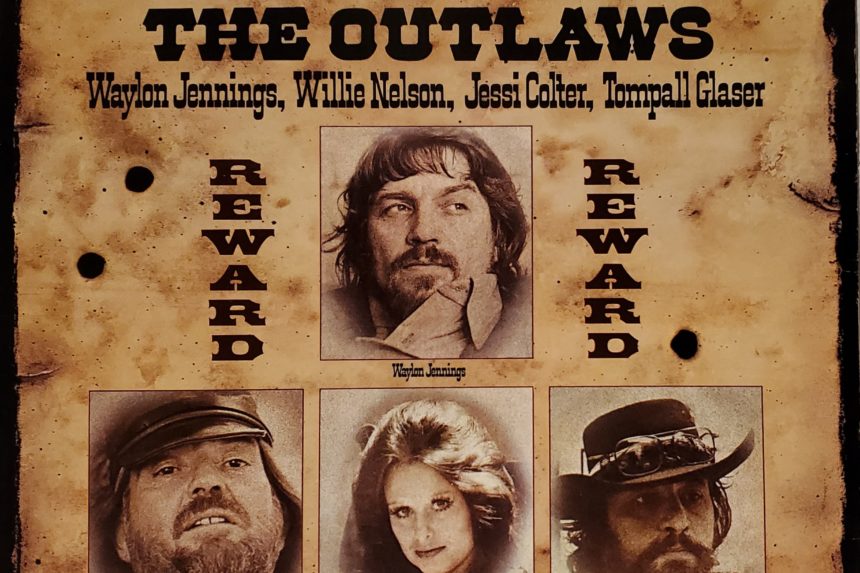

In 1976, Jennings, Nelson, Colter, and Glaser came together on an album that was perhaps the definitive statement of the movement. Wanted! The Outlaws grouped four new songs and seven older tunes for a set that was an instant crossover hit. The first track, “My Heroes Have Always Been Cowboys,” was written by Ed and Patsy Bruce and performed by Jennings; four years later, Nelson would take his own version to #1. Wanted! itself went to #1 on the Country Album chart and #10 on the Pop Album chart; it was the first country album ever to be certified platinum with sales of one million copies.

“Good Ol’ Boys” (Theme from The Dukes of Hazzard) (Uploaded to YouTube by Waylon Jennings)

However, all musical movements eventually grind to a halt. The end of the ’70s saw a new surge in pop country as artists like Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell were easily making hits on both charts. The Outlaws themselves started to turn on their own images; some did it because their musical voices led them in other directions, while others distanced themselves from their hard partying ways as they got older. Around this time, Jennings got to have a little fun with his image and score an unexpected pop hit at the same time. As “The Balladeer,” he narrated the 1979-1985 CBS hit The Dukes of Hazzard and wrote and performed the theme song, “Good Ol’ Boys.” “Boys” would turn out to be the biggest hit Jennings ever had, going to #1 Country and peaking at #12 Pop.

“Highwayman” by The Highwaymen from 1990 (Uploaded to YouTube by The Highwaymen)

The ’80s saw a neo-traditionalist countermovement in Country. Pop confections existed alongside a whole new influx of players with (George Strait, Clint Black, Garth Brooks) and without (Marty Stuart, Travis Tritt) hats. Some of the artists evoked the singer-songwriter sensibility, while others went all in on a new version of the Outlaw image. Jennings, Nelson, and Kristofferson joined forces with maybe the most legendary country outlaw of them all, Johnny Cash, for a supergroup called The Highwaymen. The group’s self-titled debut album went to #1 in 1985; they made three albums and toured into the ’90s until the waning health of Cash and Jennings took them off the road.

Brandi Carlile performs “The Joke” at The Grammys (Uploaded to YouTube by Brandi Carlile)

Waylon Jennings passed away in 2002; Cash followed in 2003 and Glaser in 2013. Nelson, Kristofferson and Colter all still operate in varying capacities, and have seen the legacies of their work manifest in the determination of artists to control their own destinies. Jennings and Colter’s son, Shooter Jennings, is a country star in his own right while retaining the independent spirit of his parents. In 2018, he co-produced Brandi Carlile’s By the Way, I Forgive You, which won three Grammys. The following year, Carlile formed a supergroup of independently-minded female country artists with Amanda Shires, Maren Morris, and Natalie Hemby. Their name, perhaps not so coincidentally, is The Highwomen.

The peak of Outlaw Country might have been short in the number of years but is vast in the ripple of influence. Even if they don’t consciously acknowledge it, it’s present in every long-haired country singer, every Nashville contract that guarantees creative freedom, and every track that’s augmented by the unmistakable distortion of rockin’ guitar. Jennings may have been haunted by his early brush with fate, but maybe he was meant to cheat death to positively impact the generations of artists that followed him and Holly. Sounds like something an Outlaw would do.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Mr. Randolph,

I chose to emphasize Waylon Jennings as the genesis for the article was the 50th anniversary of “Ladies Love Outlaws.” When doing a survey piece, we sometimes make choices like that.

By the way, here’s me on Austin City Limits from 2020:

“Recorded live in Austin, Texas, which proclaims itself the “Live Music Capital of the World,” Austin City Limits has been running live performances by acts from a variety of genres since 1976. It’s the only TV show to be awarded the National Medal of Arts. Legends that have appeared the show include Willie Nelson (who was in the pilot episode), Ray Charles, Roy Orbison, and Loretta Lynn; recent episodes have included younger acts like St. Vincent, Kacey Musgraves, Billie Eilish, and Run the Jewels.”

https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2020/10/the-10-most-important-pbs-programs-of-all-time/

Thanks for reading!

You’ve omitted a crucial step in this tale. In 1975, Willie Nelson had an album, Red Headed Stranger, that broke many creative and cultural barriers for the outlaw movement. His “Picnics” were a nursery for young artists to follow suit .

His impact on Austin when he moved here is legendary, along with Armadillo World Headquarters , ” cosmic cowboy” culture . Waylon made his contributions, though you may have ignored Austin City Limits on PBS effects , as well. Willie was 1st act, Billy Jo Shaver ( wrote Waylon’s best tunes ) , and others are archived to watch forever. Waiting on you, son.

You have inaccurate information in your story on the outlaw country movement. Mommas don’t let your babies grow up to be cowboys was written by the late Ed Bruce. He may have collaborated with Ms. Vaughn but Ed Bruce penned the song. I suggest you refer to the music of Ed Bruce and see for yourself. Just thought you should be made aware.