This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

As we begin this year’s Black History Month, the very idea of teaching and learning about Black history is under sustained attack. The state of Florida is an epicenter for those conflicts, from the DeSantis administration’s choice not to certify the new AP African American Studies course to the recent stories of teachers forced to remove books about Black history (among many other subjects) from their classroom libraries. But around the country, the numerous anti-education laws passed by state legislatures over the last few years have consistently targeted texts and themes around race, racism, and antiracism. The implication, one often stated overtly by these laws and their supporters, is that students at all levels of education are being far too frequently “indoctrinated” by lessons on subjects like Black history.

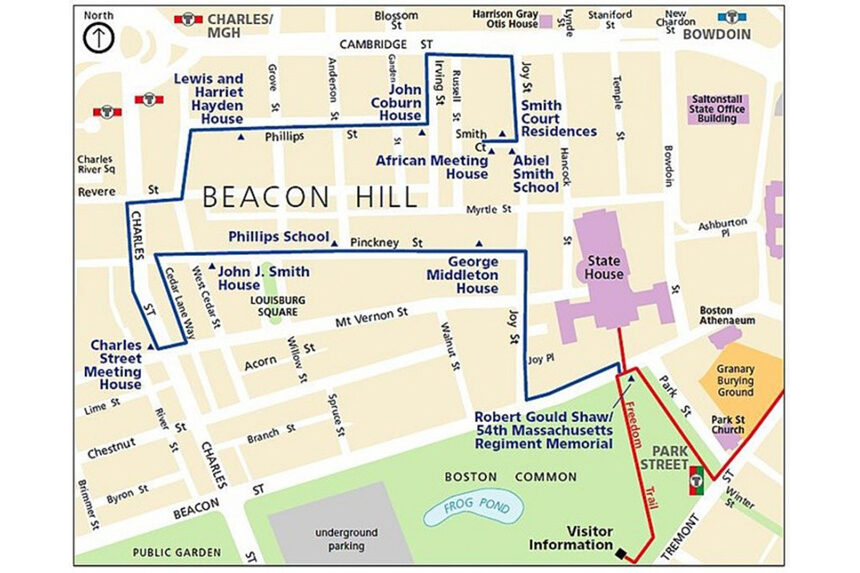

There would be many ways to argue in opposition to these laws, but one of the most ironic yet important is to recognize that there is still so much of that history that remains untaught, unlearned, and largely unknown for far too many Americans. A walk down Boston’s Black Heritage Trail, a multi-layered and moving historic site that is far less famous than its linked counterpart the Freedom Trail, exemplifies how much we still have to learn about Black and American history.

Boston’s Freedom Trail is one of the most famous and frequently visited historic sites in the nation. The 2.5-mile-long path, marked in red paint that guides tourists every step of the way, visits 16 sites connected to some of the most iconic figures and events in early American history: the Granary Burying Ground that includes such luminaries as John Hancock, Samuel Adams, Paul Revere, and Ben Franklin’s parents; Revere’s North End home and the Old North Church so linked to his midnight ride; the Boston Massacre Site; and the USS Constitution, among many other sites. Over 4 million visitors walk the Trail annually, reinforcing the prominence of these sites in our collective memories.

Those figures, events, and stories are indeed important and worth remembering, but they’re also already quite well-known. I would venture to guess that very few of the visitors or even many locals know of the Black Heritage Trail that proceeds from the Shaw Memorial through Beacon Hill. The centerpiece of the trail is the excellent Museum of African American History, but the individual sites along the way likewise illustrate figures and histories well worth adding to our sense of early America.

One of those sites, the George Middleton House, adds a vital layer to the Revolutionary and Founding-era histories so central to the Freedom Trail. Middleton, who built and lived in the house in the same year that the Constitution was drafted, was a leader of the Bucks of America, a Revolutionary War militia made of Black Bostonians that fought as part of the Minutemen, who were so instrumental to the Revolution’s origins and early battles. After the war he became a crucial community leader, co-founding the city’s African Benevolent Society and serving as a Grand Master of the Prince Hall Masons, both groups that helped establish civic identity for not only the city but also the new nation.

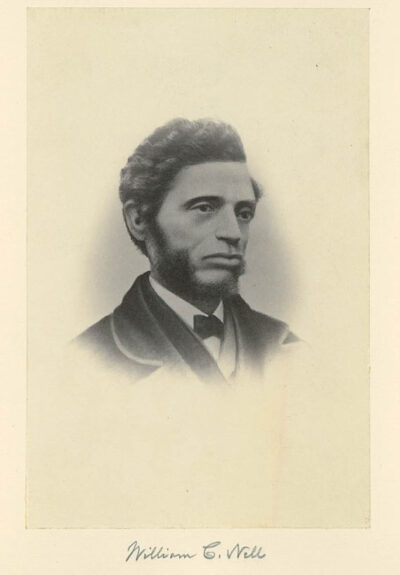

As that city and nation continued to develop in the Early Republic, the Beacon Hill Black community played a continuing role, one exemplified by a number of Black Heritage Trail sites. The African Meeting House, which opened in 1806 and is the oldest surviving Black church building in America, became known as the “Black Faneuil Hall” for how central it was to the community’s civic, religious, social, and activist efforts. The Abiel Smith School was opened in 1835 as the first dedicated Black public school in America, one that built on the longstanding efforts of the community’s African School (which for a time was housed in the African Meeting House) but offered a more permanent space for that educational and civic work. One of its most prominent students, the journalist and abolitionist William Cooper Nell, would go on to trace these histories in works like The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution (1855).

Nell was far from the only abolitionist to grow up and work in the Black Beacon Hill neighborhood; the Black Heritage Trail features a number of important sites tied to that community. The Lewis and Harriet Hayden House was owned by a pair of escaped enslaved people who turned their home into the city’s most active Underground Railroad station, sheltering famous fugitives like William and Ellen Craft, among countless others. Another Black Heritage Trail site was home at different times to two of the period’s most impressive abolitionist authors and orators: David Walker, whose David Walker’s Appeal (1829) offered an impassioned and righteous call for Black Americans, and indeed all Americans, to resist and overthrow the system of slavery; and Maria Stewart, one of the first women to speak in public in the United States and one who linked abolitionism to women’s rights in vital texts like Religion and the Pure Principles of Morality (1831), published by fellow Bostonian William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator newspaper.

In 1835, just four years after publishing Stewart’s book, Garrison was attacked and nearly lynched by a crowd of Boston white supremacists. They did not succeed in stopping Garrison’s abolitionist activism, no more than such prejudices and could minimize the importance of Black Beacon Hill. But prejudice has nonetheless contributed to our failure over the subsequent centuries to remember nearly well enough these stories. It is even more important than ever that we walk, remember, and carry forward the American lessons of the Black Heritage Trail.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now