Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

When the Global Maritime Distress and Safety System was implemented in 1999, SOS, that well-known “send help!” code that The Police sang about, officially became a phenomenon of the 20th century — in international maritime travel, anyway. It had already had and will continue to have a different life in the hands of the general public, of course, much like Morse code itself. But what does SOS actually mean?

You’ll find claims out there that it’s an initialism for “Save Our Ship” or “Save Our Souls,” or even the grim “Save Our Survivors,” but the truth is that, when it was proposed, it wasn’t an abbreviation for anything.

At the beginning of the 20th century, advancements in wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy — that is, sending text messages over radio waves — were expanding the benefits of the wired telegraph system into new areas. Wireless transmissions were particularly useful in the maritime sphere, where wired connections were impossible. But in order for the system to be truly useful in international waters, some basic standards needed to be agreed upon.

Notice I used the word international; that’s one clue that dispels the idea of SOS meaning “save our ship”: It’s in English. Though English was on its way to becoming a global lingua franca, at the beginning of the 20th century, French was still the primary language for international communication. “Save Our Ship” in French is Sauvez Notre Navire.

In 1903, at the Preliminary Conference on Wireless Telegraphy in Berlin, the need to establish a standard distress signal was raised: Ships encountered problems all the time. But no conclusions were reached — individual organizations were on their own to decide how to call for help.

The next year, the Marconi Company — a leader in radiotelegraphy, established in the United Kingdom in 1897 by Guglielmo Marconi himself — issued a statement to its operators that the code CQD would henceforth be used as a distress signal. The code CQ was a holdover from the wired telegraph indicating that the message that followed was a general broadcast, intended for all stations that received it and not for a specific location. The D was to indicate “distress.”

A little later, the U.S. Navy proposed reusing the distress code NC from the International Code of Signals — used in flag-based and signal-lamp communications. The German government called for operators to use the code SOE, which worked in a way similar to CQD.

The problem with having multiple distress signals is obvious now — and it was then, too. So in 1906, the need to create a universal distress signal was considered once again, at the International Radio Telegraphic Convention. The responsible committee preferred Germany’s SOE, but worried that the single dit of the Morse code letter E could be easily lost. They replaced it with the longer, three-dit S, not because it stood for anything in particular, but because it was more difficult to mistake for something else.

Furthermore, SOS was to be transmitted as a single code, with no spaces between letters. The symmetry and length of this new distress call made for a code that was easy for even the untrained to transmit and was difficult to misunderstand.

In later years, when the code found use outside of radio telegraphy, a further benefit was discovered: SOS looks exactly the same if you turn it upside down (making it an ambigram). If you’re, say, stranded on an island and you create a giant SOS out of rocks on the beach, it looks the same from the air in any direction. (Unlike HELP, which looks like d73H upside down and takes longer to create anyway.)

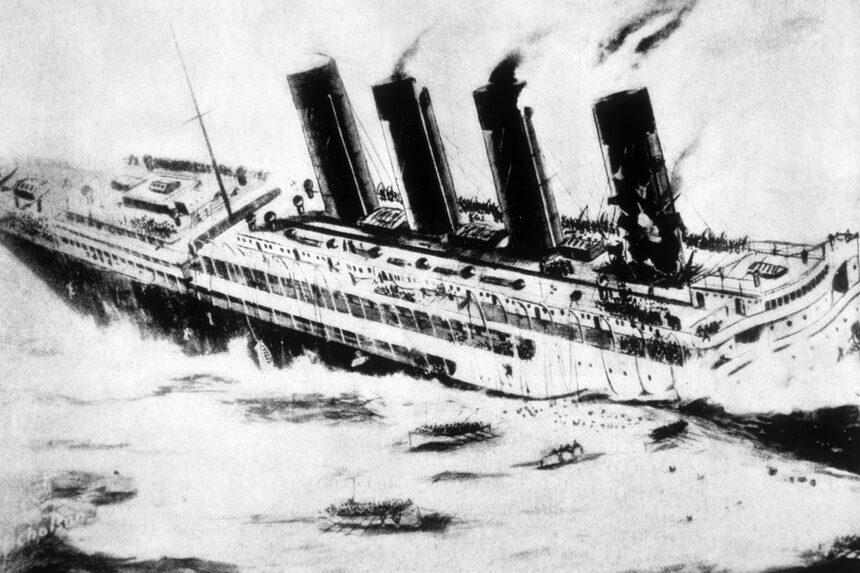

As a side note: The communications officers on the Titanic were Marconi Company men. When the ship struck ice in 1912, their first distress signal began with CQD, but they transmitted both CQD and SOS so there could be no mistaking that they needed assistance.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Correction on : “Save Our Ship” in French is Suavez Notre Navire.

Should be “Sauvez” instead of suavez.

Just from this week’s title I’ve now got ‘Sending Out an SOS’ and ‘Can’t Get It Out of my Head’ stuck in my head, the latter due to the former. That’s fine; I love both of them. Quite the interesting feature. ‘SOS’ seems like it’s permanently hard-wired as a distress/help message primarily at sea, and will probably remain as such for many years to come.