Ablutions

Rayna

Rayna sat in front of the mirror removing her makeup and wondered who she would discover underneath. It was always the most exciting part of her day, if she was being honest with herself. She rarely deigned to be honest with herself or others, and frankly found the whole concept a bit outré. Outré was Rayna’s girlfriend’s mother’s word of the week.

Some days — after using cold cream to remove the multiple layers of contouring and concealer — she would find a young maid, skin as smooth as silk, a flush high on her cheeks. Other days there would be an old crone staring back from her vanity mirror, eyes framed by wrinkles Rayna hoped came from smiling or long walks in the sun. A small mole on her nose was suspiciously shaped, a spider crawling its cancerous way across her face.

She often wondered if the face she unearthed at the end of the day could be predicted by, or correlated with, anything particular. She kept meticulous notes on her diet, her activities, the status of her menstruation. For almost a year, she was convinced that eating more rutabaga in a given week had led to a long bout of freckles with a little button of a nose. But the next time she roasted the roots, freshly pulled from their garden patch, she found cold, gray skin sloughing off her cheekbones and hadn’t touched the tubers since.

As a young girl, Rayna had loved watching her mother sit at her vanity in the evening, the transformation that happened from the carefully sculpted woman the world saw to the changing face under it all. She always found it difficult to look at her mother’s face when it was made up, deft shadows and highlights creating a mask of pigment that was unchanging. You could identify her when she was walking down the street by the coral lipstick alone. But underneath … that’s where her real mother was.

Even when she started to get sick, Rayna’s mother still got up each morning and applied her war paint, insisting that looking good led to feeling good. She must have been on to something because each night she wiped away the powders and creams, her face was younger and younger until all of a sudden it wasn’t.

The coolness of the cream on her face kept the heat from her rising temper in check as Rayna was reminded of the argument with her father and sister over the funeral. They’d insisted the mortician apply her makeup, just like her mother had always done it, and Rayna had wanted to lay her to rest with her real face. Her naked face. The one that was by turns surprising, and comforting, and terrifying. She had been overruled, and the whole service felt like a farce. Just an act for the stranger in the coffin.

As Rayna wiped the cold cream from her face this evening, with the washcloth dipped in the steaming water in the sink, her face came away entirely with the blush and eyeshadow and lipstick. Rayna regarded the blank oval in the mirror in front of her, turning this way and that, running one hand down the smooth, featureless plane. This might be her favorite face of all. Simple. Windowless.

“Good night, Rayna,” her father called from the hallway, his steps shuffling past the door. Even when she was younger, her father had never picked up his feet, her childhood memories full of the tingling shock accompanying his finger tapping her nose.

Rayna would have answered sleep tight had the day left her any mouth at all.

Thomas, Extant

Thomas hadn’t expected to be alive when the town’s time capsule was opened. After all, it was supposed to be opened after 200 years. Now here they were, cracking the seal at barely 37 years. He remembered when he had placed the metal box within the fresh-poured concrete of the statue pedestal, his nose twitching and tickling with the construction dust, the damp earthen scent of the concrete tasting like clay on his tongue.

His classmates had such high hopes when they filled the oversized box, every high school senior contributing an item — approved by the principal, of course. Students deliberated for weeks before deciding on which treasure they wanted to sacrifice to future anthropologists. Surely those lauded scientists would want to experience our music (cassettes become unplayable after 30 years), read the poetry the Honors English class wrote (they thought their teacher didn’t catch all the drug references), or learn to play the game that filled their lunch hours with little discs of cardboard (for some reason named after POG juice).

The day they had closed the time capsule, his then-girlfriend, now late wife, had posed, smiling, for the yearbook camera with the open box. The photographer took forever setting the lighting up just right to catch the contents and her face, made up just so, and shining bright enough to throw off the white balance of the shot. Even then, her coral lipstick drew your eye to her mouth. The perfectly contoured planes of her face trapping your attention as she slipped the envelope into the box while closing the lid and holding it for me as I sealed it with wax. It took three of us football players to carry the heavy cask out to the half-built statue pedestal and drop it into the ground.

The “Indian” statue raised over their time capsule was an unfortunate choice, selected by the board of white men who ran the school district before young adult books taught kids to question authority and rebel when they didn’t like the answers. All Thomas knew was that he was grateful that his construction company had been selected to remove the offensive, poorly sculpted figure, dissolving in the acid rains. Grateful that the school had decided to move the time capsule from its corroding container into something more archival safe.

Grateful that his late wife’s contribution had been slipped into the crate at the last minute, just before the lid was secured and sealed with wax.

With a glance and a nod for his two daughters standing at the front of the ten-person crowd, Thomas levered his crowbar around the seam, sending cracklings of wax scattering across the tulips. The lid slipped from Thomas’s fingers, raising a dust cloud that caused coughing fits as his hand slipped into the box, then into his pocket. A slip of an envelope, filled with words, words his wife had begged him to get rid of. Thomas had promised to bring them back to her before … before.

He’d never asked what was in the envelope she’d put into the time capsule. It didn’t seem important at the end, her life slipping away faster and faster. She made him promise not to read it. Not to tell their daughters. To destroy it. So when their girls told him he should pass the removal job to someone else, that it was too soon, that no one expected him to be able to work right now, he just shook his head and claimed he wanted to be doing something, anything, else.

He had his suspicions, of course. His wife had a singular talent for reading people, for looking at the way they stood, the way they dressed, the way they didn’t speak, and knowing things about them they didn’t know about themselves. More than once, she’d gotten herself into trouble commenting on broken marriages, dead pets, and lost dreams. Out of trouble, too, by comforting people about losses they hadn’t even recognized yet. If he’d learned anything in being with her for nearly forty years, the envelope was full of delightfully accurate yet harsh predictions about people still alive in this town. A parlor trick for the future.

Under the cover of clumsiness, he took back her words one more time.

When the dust cleared, he apologized for his stiff fingers, before stepping aside so that the white men who now sat on the board of the school district could step forward to have their photo taken with the rainbow of plastic toys, mildewing paper, and dissolving acetate, jumbled together in the rusting vault.

Lily

Lily unlocked the back door of the thrift store using a key that didn’t belong to her. Her mother had hated when Lily called it the thrift store. Consignment shop, she would correct, all while pretending to push a pair of glasses up her nose. Always “consignment shop,” because if you use fancier words, you can charge more.

Her mother’s keyring was heavy with keys from long-forgotten doors and keychains from vacations so old the enamel was entirely worn away. Lily’s father used to joke that if his wife ever needed to defend herself, the keyring doubled as a deadly weapon and to be careful not to catch a felony charge.

They hadn’t helped defend her mother in the end, but holding the jangling pile of metal and guessing at what the blank silver charms used to say still made Lily smile, which was as close to laughing as she got these days.

Rayna had suggested, and their father had agreed, that it was time to close up the shop. They didn’t have the intention or attention to deal with the lingering orders and consignments and books, and they sure didn’t trust Little Lily to handle things all by herself. Even though she’d worked in the store with her mother for the last decade, had been in charge of the appraisals for the last three years, and had been the sole employee for the last …

Their mother hadn’t been able to work much before the end.

Lily tossed the keys on the counter, half expecting the crashing weight to break the glass top, flinching on instinct, but she didn’t hear them land. She redirected her steps to the till, scouring the ground for the guinea-pig-sized ball of shiny. It hadn’t fallen short, nor had it overshot its destination. She retraced her steps and mimed throwing at first, trying to figure out where it must have landed, and when that failed, started pulling objects off the shelves of about the right weight and size to re-create her toss.

It was like watching someone vandalize the store, but very precisely, and in slow motion. Deliberate aim, toss, investigate.

Aim, toss, investigate.

Aim, toss …

The chunky, gaudy, and hideously expensive statement necklace landed on the thick ergonomic standing pad, slid under the edge of the counter, and vanished. Crawling forward, Lily reached her hand under the counter, into a shadow that she would have sworn was the base of the cabinet a moment ago. Her hand traveled farther in than she had expected.

If only she had replaced the batteries in the emergency flashlight like her mother had asked her to, months ago, this might be a little bit easier. Instead, she reached in again, refusing to think about the images of spiders and rats and snakes her brain helpfully offered to her. She didn’t have to reach far before her hand met an accordion folder. And another.

And another.

The mound of folders in front of her grew steadily until she was sure the dark space could not hold anything more, but reached back in one last time, just to be sure.

Out came the keys.

The fact that this violated the last in, first out principle of physics didn’t bother Lily so much as the sheer mass of paper which should not have been able to fit under the counter in the first place. Picking up one of the folders, she saw it had the name of the mayor’s wife on the label. Inside was a spreadsheet of all the clothing the woman had brought in over the years, which by itself wouldn’t be terribly unusual, but what was it doing handwritten here instead of in the tidy digital database Lily had maintained for her mother? After each entry was a list of receipts, gum wrappers, candies, lozenges, whatever must have been in the pockets of the clothes. The same detritus that was sliding back and forth over the bottom of the accordion folder now.

As the list continued, Lily found more observations from her mother beyond the physical: Madame First Lady came in right before closing, avoiding being seen. Madame First Lady right after Christmas selling off never-worn designers. Madame First Lady comes back with heavy makeup and sunglasses to retrieve a purse she couldn’t bear to part with after all, she claimed.

There were folders for everyone who sold clothes and accessories to them. The pastor, the pastor’s wife, school teachers, and lawyers, and housewives, and police officers.

A folder for Rayna: empty blush compacts and broken mirror shards.

For Thomas: sawdust and calluses.

And Lily: a single key on a blank keychain.

Lily stared at the key, running her fingers over the blank metal tag hanging next to it, trying to decipher the remains of some enamel or engraving, but came up with nothing. She gathered up the folders and rearranged them neatly in the space beneath the register. Alphabetical so she knew exactly which one she’d be pulling out when she reached into the dark. Then she spent a few minutes tidying up the stock she had tossed around the store, and finally went to unlock the front door to open for customers.

Hesitating at the doors, Lily balanced her mother’s mass of keys in one hand and the single blank key in her other. The only thing in the folder labeled with her name. Slowly, she reached out the new key, slipping it into the lock.

She left it there for a moment, the solo key with the bright tag swinging and glinting. Then, taking a deep breath, Lily unlocked the store with her key.

Thomas, Departed

When he died, their father had two requests.

Well, actually, he had a whole will, leaving controlling interest in his construction company split between Rayna and Lily, though he expected they’d probably sell it to his business partner. He left the house to Rayna, who hoped her boyfriend would propose soon so they could start a family. The consignment shop to Lily, though she really should close it and find something constructive to do with her life.

And a letter wrapped around a sealed green envelope. The ink sweeping across the green paper had faded to a rusty brown, but was unmistakably their mother’s handwriting: Open after 100 years!

Curious, the women leaned over the white paper covered in their father’s spiky handwriting to read together. He wrote that he loved them both very much. That their mother, while she lay dying, had begged him to retrieve this envelope from the aborted time capsule at the school, which he was being hired to remove. That he had insisted on taking down the statue at the school not because he was stubborn in avoiding his grief, but because he was following her last wishes. Now, given that they were reading this, he had died unexpectedly before he could bring himself to destroy this last piece of his wife.

He’d never opened the envelope. Never read the words she’d written down, sitting on the stage in the cafeteria, partially obscured by the dusty, nonfunctioning stage curtains. Their father knew just what sort of trouble his wife couldn’t help but cause with just a few words, and this envelope contained a multitude, judging by its thickness.

Once, in their sophomore biology class, she had stopped by their teacher’s desk on the way out the door to comment: “I am glad you didn’t change your perfume; rosewater works so well on you. I thought you had, since your husband dropped off his cleaning at my parents’ shop yesterday and they just reeked of Chanel No. 5.” They never saw Mrs. Peterson again, and rumor had it she killed her husband that night. Really, she’d left him and moved out of town, but teenagers will talk.

It wasn’t that their mother meant to cause trouble; the words just wouldn’t stay down when she noticed something. She’d tried, holding in those burbling phonemes, keeping her lips pressed tight until they slipped out at inopportune moments, during an address to the student body, or at a work meeting. It was always better if she found a private moment to deliver them, to reduce the catastrophic effects to just the immediate parties.

Right after their parent’s wedding, they met another couple at their honeymoon beach resort. They were young, loved sharing their toast in the morning (she ate crusts, he ate soggy centers), and came from a town not too far from their own. On the last day, their father’s new wife (his wife! How exciting that was to say) approached the other bride. “I’m terribly sorry about your husband’s diagnosis, I’m in awe of how brave you are, marrying him anyway.”

The other woman clutched at their mother’s arm as they walked away, asking what diagnosis, what was she talking about? But their parents had a plane to catch, so they grabbed their luggage and left. Their father had seen the aftermath of her casual truths too often to want to try explaining. Less than a year later his obituary was in the paper.

This was why their father had resisted reading the letter rescued from the failed time capsule. He had kept it in the pocket of his jacket for the last year, its nearness a salve for the open wounds he carried on his heart. He hid from the predictions his wife had made; he didn’t want to know how many of them had come to pass. Whether they had so few arguments because she saw them coming and already knew how to resolve them. Whether she knew they’d lose one child before they were born, and another to illness as an infant. Whether she knew she would die slowly and painfully from the very beginning. That she would leave him long before he was ready.

Nor could he cast those words into the void, unread, unremembered.

So he had two requests: read the letter, and then destroy it.

Rayna put down their father’s letter, and the two of them stared at the green envelope, with its faded admonition to open in another 62 years. She pushed it over to Lily. “You open it.”

Lily fingered the key to the consignment shop in her pocket, the key her mother had gifted her. Her mother’s shop was hers now, free and clear. No matter what her sister wanted, that store would stay open for as long as Lily drew breath.

“I think you should open it.” Lily pushed the envelope back to Rayna.

Even though she’d been crying earlier that morning, Rayna’s makeup was impeccable, as always. Her mother had taught her all the tricks for hardening the paint on her face to the point that a little water did no harm. How to blot her eyes so as not to leave streaks of mascara. How to apply foundation with just a hint of glitter so that perspiration only amplified your glow.

The two sisters sat there, debating with themselves and occasionally each other over whether it was their right, their obligation, to open the envelope. Their father had obviously wished to have their mother’s words known, but at the same time their mother had wanted them to fade into obscurity. Neither parent had bothered to ask what their girls thought about the whole situation.

Rayna fingered the flap, the glue failing, leaving it haphazardly sealed. “Imagine what sort of predictions she might have. There might even be something to help.”

“Help us how? What use is knowing who is leaving who? Who is sleeping with who? Who is going to break confidence with who? It never turned out well when folk knew, did it?” Lily retrieved the letter from her sister and set it back on the desk, tucked into the blanket of their father’s last letter.

It had gotten dark in the room without the sisters realizing it, and Rayna leaned over to turn on a lamp. “There’s no reason to decide now, is there?”

Lily agreed, and they settled on having a light dinner, scavenged from the acres of food people had been delivering all day, before making their way to an early bed. The house settled into its night rhythms. The gentle hum of the refrigerator. The warm wind whistling through the air vents. A silence where there was once a harumph and clearing of a throat, filled now with the soft step of a foot on the stairwell.

She crept down the stairs, skipping the second to last, which would let out an audible creak, deafening in the middle of the night. After a lifetime of avoiding the furniture, it was second nature, and she slipped carefully through the dark until she reached her father’s office and picked up the green envelope from the desk where they had left it.

For the briefest of moments she considered ripping it open, but instead went to the corner and slipped the envelope whole into the waiting slot, the switch already set to automatic. The shredder roared to life, grinding the letter into tiny pieces of confetti.

News of the Week: Top Cities, Rod Serling, and Cereal Isn’t Just For Breakfast Anymore

“Please come to Boston for the springtime … “

And the Best U.S. City to Live in Is …

… Cambridge, Massachusetts.

That’s according to data collected by Niche, a site that helps people find the best places to live. Other cities in the top ten include Arlington, Virginia; Naperville, Illinois; Irvine, California; and Ann Arbor, Michigan.

The criteria for the list includes affordability, neighborhood diversity, public schools, and the number of Dunkin’ Donuts shops in the area, apparently.

Submitted for Your Approval …

I’m rather surprised that there isn’t already a statue of Twilight Zone creator/host Rod Serling in his hometown of Binghamton, New York. But a Kickstarter has been launched to get the statue up and dedicated, and there’s still time for you to contribute (it ends this Monday)! And if you contribute $50 or more, you get your choice of a calendar or a T-shirt. Contribute more than that and you get them both and maybe even a brick you can have personally inscribed and placed at the base of the statue.

From the pictures, it looks like we’re thankfully not going to have another Lucy situation on our hands.

Midnight Snack

A lot of people eat breakfast for lunch, dinner, and late at night (paging Jerry Seinfeld), but now you can do it at night without feeling bad about it.

Post has come out with two new kinds of cereal called Sweet Dreams. One is Blueberry Midnight and the other is Honey Moonglow. Both contain “an herbal blend of lavender and chamomile, and curated vitamins and minerals like zinc, folic acid, and B vitamins to support natural melatonin production.”

(That means they can help you get a good night’s sleep.)

I wonder if it’s okay to eat these cereals in the morning too, or will you find yourself falling asleep at your desk?

In other breakfast news, Cup Noodles — which I have always called Cup O’Noodles, though that name was retired in 1993 — has a new ramen flavored like pancakes, maple syrup, sausage, and egg.

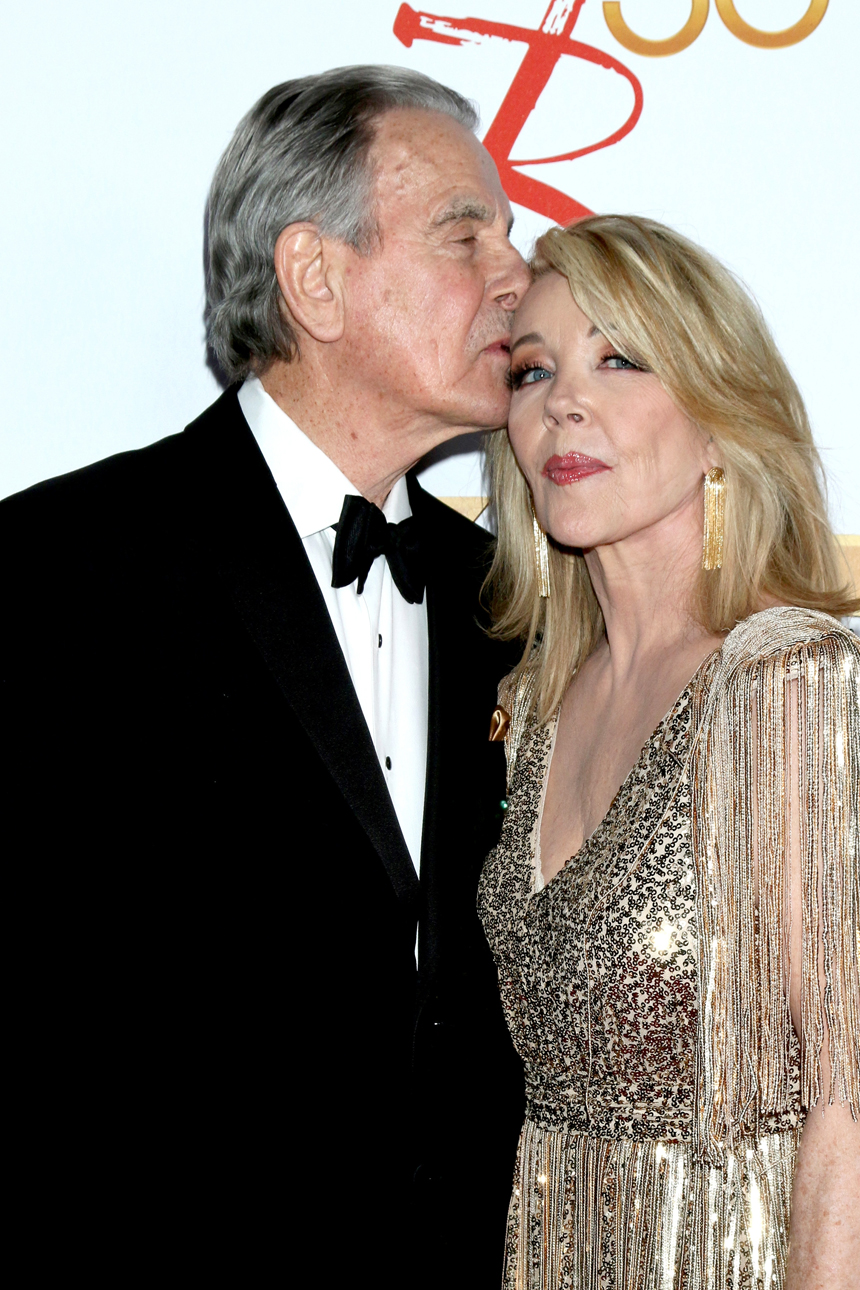

50 Years of The Young and the Restless

I’m not saying I watch CBS’s The Young and the Restless every day at 12:30 p.m., but I will say that I’m rather stunned at the lengths Phyllis has gone to get rid of Diane. Teaming up with Stark? What is she thinking? I don’t 100 percent trust Diane, but Phyllis has gone off the rails. And why does Victor always seem to win, and why has Victoria turned almost evil, and why does it seem like there’s only one coffee shop in town? Don’t they have a Dunkin’?

That’s the type of stuff I would say if, you know, I watched the show every day.

The popular soap set in Genoa City, Wisconsin, is celebrating 50 years this week. Stars that used to be on the show include Tom Selleck, Eva Longoria, David Hasselhoff, and Paul Walker.

100 Years of Warner Bros.

The Warner Bros. studio is twice the age of The Young and the Restless, and to celebrate, Turner Classic Movies will be showing a marathon of all WB films throughout the month of April. It starts tomorrow with 1924’s Beau Brummel. Here’s the full schedule (PDF).

RIP Bill Zehme, Gordon Moore, Norman Steinberg, Hal Dresner, Connie Martinson, and Bobbi Ercoline

Bill Zehme was an acclaimed journalist and author who wrote books and features on such people as Johnny Carson, David Letterman, Jay Leno, Frank Sinatra, Hugh Hefner, and Regis Philbin. He wrote for such publications as Esquire, Playboy, Vanity Fair, and Rolling Stone. He died Sunday at the age of 64.

Gordon Moore was the co-founder and former chairman of Intel and one of the people responsible for the way we use computers today. He created what became known as Moore’s Law, which says that the number of transistors placed on a microchip will double every two years. He died last week at the age of 94.

Norman Steinberg co-wrote the Mel Brooks comedy Blazing Saddles as well as movies like My Favorite Year, Johnny Dangerously, the classic Marlo Thomas TV movie Free to Be … You & Me, and TV shows like Flip and Doctor Doctor. He died earlier this month at the age of 83.

Hal Dresner co-wrote such movies as Cool Hand Luke (for which he was uncredited), The Eiger Sanction, and Zorro: The Gay Blade, and wrote for TV shows like M*A*S*H, Night Gallery, and The Harvey Korman Show. He died last week at the age of 85.

Connie Martinson was the longtime host of the Los Angeles cable books show Connie Martinson Talks Books. She died earlier this month at the age of 90.

Bobbi Ercoline is the woman hugging her boyfriend on the classic cover of the Woodstock soundtrack album. She died last week at the age of 73.

This Week in History

Triangle Shirtwaist Fire (March 25, 1911)

The Greenwich Village factory fire killed 146 garment workers, most of them young girls.

Sacheen Littlefeather Declines Oscar for Marlon Brando (March 27, 1973)

The actress and activist declined the Best Actor award at Brando’s request to protest the way Hollywood depicts Native Americans. She died in October.

Uploaded to YouTube by Oscars

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: Ralston Breakfast Food (March 25, 1905)

Yes, “breakfast food” seems like a generic term, but at least it’s brown.

Cereal Recipes

Note: These are recipes you make with cereal. I’m not going to tell you how to make homemade Cheerios or Froot Loops.

For example, take a look at these Cap’n Crunch Chicken Strips from The Pioneer Woman or the Cinnamon Toast Crunch French Toast (spoiler alert: it uses Cinnamon Toast Crunch cereal) from Lauren’s Latest. Taste of Home has snacks called Cheese Crispies (which have shredded cheddar cheese, Rice Krispies, and pecans) and also Gobbler Cakes, which you can make with turkey, stuffing, cranberries, and corn flakes.

By the way, did you know there is a serious debate going on right now as to whether or not cereal can be considered a soup? I think what this means is that if people can eat cereal late at night, we’re going to start seeing people eat soup at breakfast.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

April Fools’ Day (April 1)

Here’s a funny joke to play on your kids: replace their sugary morning cereal with Brussels sprouts. Tell them it’s a new cereal called Sprouts! and the mascot is a talking Brussels sprout. Throw in a Belgian waffle to make the scam seem more believable.

Men’s Final Four (April 1 and 3)

How did you do with your bracket? I ask that like I know something about March Madness. But the final four have made it to, well, the Final Four, and those teams are the University of Connecticut, San Diego State, Miami, and Florida Atlantic. CBS and the CBS Sports Network will have the action starting at 6 p.m. EDT on Saturday. The championship game airs Monday at 9 p.m.

Our Better Nature: Why Springtime Smells Like Springtime

In addition to its longer days, I look forward to spring’s warmer temperatures, distinct lack of snow, and especially its fragrance. To me, spring smells like the promise of renewed life as the soil awakens and green leaves burst forth. “Earthy” is the descriptor often used for this welcome perfume. I find it intoxicating. The explanation of why spring smells nice is less poetic, but it’s fun and quirky at every turn.

Spring’s aroma has long intrigued us, to the point that sixty years ago, Australian scientists gave it a name: “petrichor.” This word is derived from the Greek “smells like a rock.” Well, something like that. Shortly after the wondrous bouquet of spring got a name, British scientists found its primary source, a tertiary alcohol they dubbed “geosmin,” a Greek-based term for “smells like a rock.” In other words, the springtime “smells like a rock” aroma is principally due to the odor of “smells like a rock.” If that was your answer on a test, I’m not sure you’d get full credit for it.

To be fair, petrichor may involve other things like plant oils, but the chief contributor is geosmin. Humans can smell geosmin at very low levels, in the parts-per-trillion range. We’re actually 1,000 times better at detecting geosmin than a shark is at sensing blood at a mere one part per million. One also gets a whiff of petrichor just as a rainstorm breaks, and again right afterward.

It took a while to figure out that geosmin is made by soil bacteria in the genus Streptomyces. If that name rings a bell, it’s because the vital antibiotic streptomycin comes from these bacteria. In fact, Streptomyces bacteria give us more than two-thirds of all naturally-sourced antibiotics. It’s a little creepy to think that Streptomyces’ close relatives cause leprosy and tuberculosis, while other members of the family provide the cure. Talk about job security.

Geosmin is one of several toxins these bacteria make to kill fungi, nematodes, and other soil organisms that like to dine on them. Paradoxically, there’s one predator that they want to come devour them; getting eaten by this creature is the only way Streptomyces can survive.

The “marauder” is tiny, about one-eighth to one-sixteenth of an inch long. Known as springtails, they crave alcohol. Specifically, geosmin, which they can safely digest without suffering ill effects. Found the world over, including the polar regions, springtails are hexapods (the non-robotic kind), related to insects. Sometimes they’re called snow fleas, as they like to bop around on the snow on mild winter days. Outside of winter, they burrow through soil in search of rotting stuff to eat.

Springtails, which are thousands of times bigger than a bacterium, still find plenty to eat. How do these critters, which presumably don’t use microscopes, find prey that’s too small to see? The answer is that Streptomyces form colonies of up to several inches across, resembling patches of mold. Easy pickings for the only living thing able to eat them and not die.

The reason Streptomyces are in such a hurry to use geosmin to lure springtails to gobble up their colonies is that springtails are the perfect vectors for bacterial spores. Essential to the formation of healthy topsoil, springtails can number around 100,000 individuals per cubic yard, and they range throughout the soil profile, from the surface to quite deep down. Their high numbers and roving natures help move Streptomyces away from older colonies, which die out as available food is depleted, to far-flung locales. Some of these new neighborhoods are just right to begin fresh bacterial outposts.

Though the first bacteria appeared on Earth 3.5 billion years (give or take a couple, I imagine) ago, Streptomyces showed up about 450 million years ago. Evidently, springtails date back to the same period, so these two organisms have had copious time to perfect their symbiotic ballet. Both of them are only active in the presence of moisture, which accounts for why we notice petrichor in spring when the ground is usually moist, and around rain events.

Streptomyces have been quite generous to us in terms of the array of antibiotics derived from them, but springtails have gifted us with cool stuff, too. They make a unique protein-based antifreeze (that’s why they’re so active in winter) that may soon allow us to freeze human organs destined for transplants without damage to the organs. The same antifreeze compound is said to keep ice from forming on top of the ice cream in our freezer. Springtails are entertaining as well – they can bounce seven inches into the air, which is like one of us jumping roughly 500 feet straight up. Which would be fun, except for the return trip.

What it boils down to is that the pleasing aroma of springtime (and rainstorms) is thanks to a group of bacteria that look like fungi, urgently want to be someone’s dinner, and make deadly poisons that we use as life-saving drugs. In turn, these bacteria rely on a coterie of insect-like critters who can’t say no to alcohol, excel in outdoor winter high-jumping, and enjoy subterranean rambles. Pretty simple.

In a Word: Are You Troubled by Conscience?

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

“How do you spell conscience?” asks Carol Connelly (portrayed by Helen Hunt) while she pens a thank-you note in an intense scene from 1997’s As Good As It Gets. Her mother (played by Shirley Knight) spells it out for her, and moments later, Carol blurts out in frustration, “This can’t be right. Con-science?”

The idiom “pros and cons” has primed us to the idea that pro- and con- are opposites. As the old joke goes, “If pro is the opposite of con, what’s the opposite of progress?” The fact that progress and congress aren’t denotatively opposites is the joke.

As I pointed out in an earlier column, the opposite of the Latinate prefix pro- isn’t con- but contra-. English speakers shortened the phrase “pro and contra” to “pro and con.” (It is a bit snappier, no?)

The con- in conscience is an assimilated form of com-. “Assimilated” in this case just means that the final letter of the prefix has changed to be closer (in a phonetic sense) to the first letter of the next syllable. It happens a lot to com-, which appears in assimilated forms in words like collateral, correlate, cognition, and cooperate. Com- comes from the Latin preposition cum “with,” as in magna cum laude, literally “with great praise.”

So the con- in conscience means “with”; does that mean that conscience is really “with science.” The short answer: Yes. Conscience, traces back to the Latin verb conscire, which combines com- with scire “to know” — the source of the English word science. Conscire meant “to know together, to be mutually aware,” especially in the sense of knowing right from wrong. From conscire came the abstract noun conscientia “a joint knowledge,” which became the Old French conscience. It was in Old French that the word took on the more modern sense of conscience as “innermost thoughts” before being borrowed into English in the 12th century.

So yes, Carol Connelly, conscience really is con-science, but the earliest form of the word is old enough that it and science (which for a time was restricted to religion and philosophy) have had plenty of time to change so much that their connection isn’t so obvious anymore.

Review: Tetris — Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott

Tetris

⭐️ ⭐️ ⭐️

Rating: R

Run Time: 1 hour 58 minutes

Stars: Taron Egerton, Mara Huf, Nikita Efremov, Toby Jones, Roger Allam

Writer: Noah Pink

Director: Jon S. Baird

In theaters and on AppleTV+

Well, that’s just great. It’s been 30 years since I finally rid my head of that infernal melody from the 1990s video game Tetris. And now, thanks to the new movie retelling the game’s origins, that earworm has once more burrowed deep into my brain.

You remember it: That Russian-infused folk song that played incessantly as you frantically tried to stack an endless descent of shapes into gaps at the bottom of the screen.

You may have wondered at the time: Why that Russian folk song; and why does the game’s home screen feature onion-domed towers reminiscent of St. Basil’s Cathedral in Moscow’s Red Square?

All those questions and more are answered in Tetris, an imaginative and often charming comedy/drama bristling with characters shady and sweet, pallid and powerful, all of whom find themselves stripped to their core identities because of a deceptively simple, infuriatingly addictive video game.

Rocketman’s Taron Egerton stars as Henk Rogers, a struggling 1980s video developer trying to market his new creation, a game called “Go” (“Like chess,” he says dejectedly, “only harder”). While roaming around the exhibit floor at the Las Vegas Electronics Show, he stumbles upon a demonstration of Tetris in its embryonic form.

Realizing the game is a winner, Henk mortgages his home in Tokyo with the grudging approval of his wife, Akemi (Ayane), and buys the rights for Tetris in Japan with the intention of licensing it to the video game giant Nintendo. (A true citizen of the world, the real-life Rogers was born in the Netherlands and raised in Los Angeles before settling in Japan with his wife and daughter.)

Or at least, he thinks he’s bought the rights. Because Tetris was developed by lowly Russian computer engineer Alexey Pajitnov (Nikita Efremov), working for the government (like everybody else), and because the insular Soviet Union has no experience in international intellectual property licensing, the actual rights to Tetris are muddy, at best. Henk may own piece of Tetris — but also, he may not.

One thing’s for sure: He’s not going to get his mortgage money back.

It takes a while for writer Noah Pink (TV’s Genius) and director Jon S. Baird (Stan & Ollie) to map out Tetris’s hopelessly convoluted terrain, which hopscotches from Tokyo to London to Moscow to Seattle and back. But once they do, Henk’s story is off and running.

Those of us lacking degrees in contract law and international intellectual property rights will often find ourselves a few steps behind Henk when it comes to grasping exactly what his latest hurdle entails. But it doesn’t really matter: Among the film’s supremely likable cast, we can tell at a glance who’s a friend and who’s a foe. (Some of the characters change their stripes in mid-film, but from the moment we meet them, we know which ones they’ll be.)

Like characters in a video game, the heroes and villains are defined here with 8-bit starkness: As Alexey the game designer, a noble genius just trying to keep his head down in the brutal Soviet bureaucracy, Efremov presents a heartbreaking image of Russian people — then and now — who despair of ever enjoying Western-style freedom. Doe-eyed Mara Huf plays a KGB agent who, posing as Henk’s friendly Moscow interpreter, fools absolutely no one but him. Toby Jones pops up as a double-dealing corporate attorney who seems to have dropped in from a Ben Hecht movie. BBC veteran Roger Allam, with a booming voice and an impossibly black, suitably greasy shock of dyed hair, nearly steals the film as pompous, corrupt British tabloid king Robert Maxwell — a bully to all, including his clueless son Kevin (Anthony Boyle). As the Soviet technology official who personally likes Henk but is being pressured to hand Tetris’s rights over to the Maxwells, Ukrainian star Oleg Stefan masterfully elicits the Jedi-like power of mid-level bureaucrats who know which buttons to push and when.

With its sprightly pace, Tetris never lingers on any one chapter long enough for us to grow frustrated with our lack of insight. Plus, it’s fun to watch the characters ooh and aah over devices with the computing power of a present-day digital thermometer.

And it’s also sobering to visit the dark, somber streets of 1980s Moscow. In one poignant scene, Alexey takes Henk to an underground Moscow nightclub where the revelers — dancing to “The Final Countdown” by the Swedish group Europe — excitedly share news about the unfolding political revolt in the Balkans.

When, they wonder, will the winds of change blow through Mother Russia? Already, however, we have seen the seeds of post-Soviet corruption taking solid root in the country’s bureaucracy.

We’d like to tell these good people what lies ahead. But then again, we suspect, we wouldn’t have the heart.

ABBA at 50: Ten Major Moments

One of the best-loved music groups of all time, ABBA has also staked their claim as one of the best-selling acts in history. Members of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, with worldwide record sales estimated to be in the hundreds of millions, the quartet dominated the pop scene for most the 1970s and into the ’80s before the two married couples each divorced and went their separate musical ways. The continued popularity of their music and their increasing influence kept them in the limelight until a totally improbable reunion after a 40-year hiatus returned them to the top of the charts. Though their history is fairly intricate and spans decades, here are ten major ABBA moments.

1. Making a Name

Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus had each established themselves with popular bands in their native Sweden by the mid-1960s. Keyboard player Benny was in Hep Stars, and guitarist/vocalist Björn belonged to The Hootenanny Singers. Benny had already written a number of hits for his band before they decided to write together in 1966. The Hootenanny Singers’ manger Stig Anderson realized the possibilities that the team presented and pushed them to keep going. When one of their compositions became a contender to be Sweden’s Eurovision entry in 1969, Benny met another performer, vocalist Anni-Frid Lyngstad. They quickly became a couple, and Benny began producing some of her material. In 1969, Björn had met singer Agnetha Fältskog; she’d already had a #1 hit at the age of 18. The two would marry by 1971. Soon, all four were working together, either writing and producing on Anni-Frid or Agnetha’s solo albums or assembling material as a group. In 1972, the quartet, billed under the unwiedly name of Björn & Benny, Agnetha & Anni-Frid, released the song “People Need Love.”

2. Debut Album

“Ring Ring” (Uploaded to YouTube by ABBA)

50 years ago this week, they released their debut album, Ring Ring, again as Björn & Benny, Agnetha & Anni-Frid. However, Stig Anderson knew that the name was a non-starter in many markets. Combining the first letters of each performer’s name, he came up with the moniker they would always be known by: ABBA. Ring Ring was a hit all over Europe, setting them up for future success. In fact, it was only after the song hit that the four knew that they could, forgive me, take a chance on continuing as a group.

3. Eurovision

“Waterloo” (Uploaded to YouTube by ABBA)

After some previous disappointing swings at trying to represent Sweden in the Eurovision song contest, the group took something new to Melodifestivalen 1974, the Swedish preliminary event for Eurovision selection. ABBA submitted their glam rock-inspired tune that compared a broken love affair to a famous battle: “Waterloo.” At the time, a number of Eurovision entrants were somewhat folky (even hokey), but ABBA leaned into a pop-rock direction and made the fairly bold decision (for the time) to sing in English. The insanely catchy tune carried them to Eurovision victory on April 6, 1974. Now instantly recognizable in Europe and with a batch of fresh material, they had a significant opportunity to make real dent in the elusive U.S. market. “Waterloo” went #6 in the States, followed by the #27 “Honey Honey.” Napoleon may have failed at Waterloo, but for ABBA, it was the successful start of their own Swedish invasion.

4. 1975

“SOS” (Uploaded to YouTube by ABBA)

ABBA’s self-titled 1975 album established them as major stars in the U.S., Japan, and Australia in addition to Europe. It produced three Top 40 hits in the States: “I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do,” “SOS,” and “Mamma Mia.” The record really epitomized the ABBA sound, which is many things without being just one thing. It certainly included rock elements (consider the guitar on “Mamma Mia” or the “When you’re gone/How do I even try to go on” passage of “SOS”), but was also informed by dance music (notably disco), hook-driven pop elements, Benny’s sophisticated keyboards, folk aspects, and the absolutely killer harmonies of Anni-Frid and Agnetha. It was, for lack of a better descriptor, ABBA. In addition to touring, ABBA was able to appear around the world via music videos, over 30 of which were directed by Swedish filmmaker Lars Sven “Lasse” Hallström, who would go on to film success with movies like What’s Eating Gilbert Grape? and The Cider House Rules.

5. Dancing Queen

“Dancing Queen” (Uploaded to YouTube by ABBA)

For the next two years, ABBA would continue to crank out hits like “Fernando,” “Knowing Me, Knowing You,” and “Money, Money, Money.” But nothing could prepare anyone for what was arguably the ABBA song: “Dancing Queen.” Biographies of the group (notably 2005’s ABBA: The Complete Guide to Their Music by Carl Magnus Palm and 1995’s ABBA: The Name of the Game by Andrew Oldham, Tony Cadler, and Colin Irwin) related the emotional impact of hearing Benny’s disco-inflected musical backing track for the first time. Anni-Frid admitted to crying upon first listen, and Agnetha would say “It’s often difficult to know what will be a hit. The exception was ‘Dancing Queen.’ We all knew it was going to be massive.”

The band debuted the song in performance at perhaps the most appropriate venue possible. King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden was set to marry Silvia Sommerlath on June 19, 1976. At a televised gala held the night before at the Royal Swedish Opera, ABBA played “Dancing Queen” live for the first time. The reaction was seismic. “Dancing Queen” hit #1 in over 20 countries, including the Soviet Union (let’s repeat: #1 in Cold War 1970s Soviet Union). It would be the group’s only U.S. #1 and has been certified with sales of more than four million copies worldwide.

“Dancing Queen” is easily ABBA’s signature song. It’s exhibited an incredible cultural staying power and continues to draw praise. In their appraisal of the greatest songs of the 1970s, famously prickly music site Pitchfork heaped high praise on the tune, with Cameron Cook writing: “[the song] bottles the out-of-body euphoria that accompanies dancing for dancing’s sake, with no agenda or motive other than pure joy.” Popular and impactful, “Dancing Queen” spurred the creation of other great songs of that decade; Blondie’s Chris Stein admitted that the song was a huge influence on “Dreaming.”

6. Take A Chance on Me

“Take A Chance On Me” (Uploaded to YouTube by ABBA)

After “Dancing Queen,” ABBA’s biggest hit in America was 1978’s “Take a Chance on Me.” Proving that inspiration can come from anywhere, Björn has recounted that the song’s rhythm came from sounds he repeated to pace himself while taking runs. He and Benny turned that repetitive consonant sound into the chant-like invocation of “take-a-chance/take-a-take-a-chance-chance” that began the foundation of the track. The group harmonized the chorus while the ladies traded the verse parts. The bouncy, upbeat tune hit #3 in the U.S. It would be their penultimate Top Ten single in the States; “The Winner Takes It All” would hit #8 in 1980.

Though ABBA remained massively popular worldwide, internal tensions took a toll. Björn and Agnetha divorced in 1979, and Benny and Anni-Frid split in 1981. The band went on an official hiatus after a performance near the end of 1982. That hiatus would last almost 40 years. Benny and Björn continued to work together, co-writing the musical Chess with Tim Rice (which produced worldwide hit song “One Night in Bangkok”) and other projects. Both Agnetha and Anni-Frid had productive solo careers. But for all intents and purposes, ABBA was gone.

7. ’90s Revival

Erasure’s cover of “Take A Chance on Me” (Uploaded to YouTube by Erasureinfo)

Or was it? While the ’80s in America saw ABBA turn up as the subject of jokes in TV shows like The Facts of Life (the other girls couldn’t fathom Tootie’s fandom), the next decade would be much kinder. The 1990s saw a reinvigorated interest in the group, spurred by a variety of projects. English synth-pop duo Erasure released a four-song cover EP, Abba-esque, which was a huge hit in 1992. That same year, Benny and Björn performed “Dancing Queen” on stage with U2 at the Irish band’s Stockholm concert. That September, a new compilation, ABBA Gold: Greatest Hits, landed with a bang. “Dancing Queen” returned to the charts in a number of countries, and the collection would go on to sell 30 million copies around the world. Even parody tribute band Björn Again became a big success. Diverse contemporary artists ranging from Kurt Cobain of Nirvana to Dionne Warwick professed their admiration for the group’s music.

8. Mamma Mia and More

“Mamma Mia” (Uploaded to YouTube by ABBA)

The resurgence in interest was further propelled by the prominent deployment of ABBA songs in various films. In 1994, two Australian films, Muriel’s Wedding and The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, increased their profile at the box office dramatically with the inclusion of ABBA tunes. However, a further, massive boost would be provided by the 1999 stage musical, Mamma Mia!. With a book by the Catherine Johnson, the musical incorporated approximately 23 ABBA songs as written by Benny and Björn; it was a smash and led to a 2008 film adaptation starring Meryl Streep (as well as a film sequel).

9. Rock and Roll Hall of Fame 2010

“Does Your Mother Know” (Uploaded to YouTube by ABBA)

ABBA was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with the 2010 class; their welcome speech was presented by Barry and Robin Gibb of The Bee Gees. Anni-Frid and Benny attended to accept (Agnetha was, at the time, eschewing air travel, and Björn cited family obligations). ABBA had proven to be impervious to the “disco” stigma that plagued other acts (like the Brothers Gibb, which is why they were appropriate inductors), and the revived interest in the group and widespread admiration for Benny and Björn’s songwriting had made their eventual inclusion a forgone conclusion. Nevertheless, the four famously refuted any possibility that they’d ever reform.

10. The Return

ABBA Voyage trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by ABBA Voyage)

Never say never. In January of 2016, the four members of ABBA appeared in public together for the first time in decades for the opening of Mamma Mia!: The Party, a themed restaurant in Stockholm near the ABBA Museum. At a private party celebrating Benny and Björn’s first meeting 50 years prior that June, Anni-Frid and Agnetha sang the ABBA tune “The Way That Old Friends Do” in Benny’s honor; when Benny and Björn joined them onstage for the end of the song, it was international news. By October, British manager Simon Fuller announced that ABBA would be reassembling to record new music for what would eventually become ABBA Voyage. ABBA Voyage was a virtual residency with “ABBAtars” (digitally created avatars of the group’s younger selves, created from motion capture of the group by Industrial Light and Magic) performing in a specially designed theater. While the project saw COVID-19-related delays, the new material expanded into Voyage, an entirely new ten-song album.

“Don’t Shut Me Down (Lyric Video)” (Uploaded to YouTube by ABBA)

As you might expect, the new album was a raging success upon its November 2021 release, with “Don’t Shut Me Down” giving the group their first Swedish #1 song since 1978. ABBA Voyage sold over a million tickets for the London theater show. In March of 2023, it was announced that Voyage would hit the road, taking virtual ABBA virtually everywhere. Full details have yet to be revealed, but it’s fairly certain that the show will be warmly received by fans around the world. With their ongoing success, their seemingly timeless songs, and an obvious appetite for the group’s work, it doesn’t appear anyone or anything will be shutting ABBA down anytime soon.

Vintage Ads: March 1823

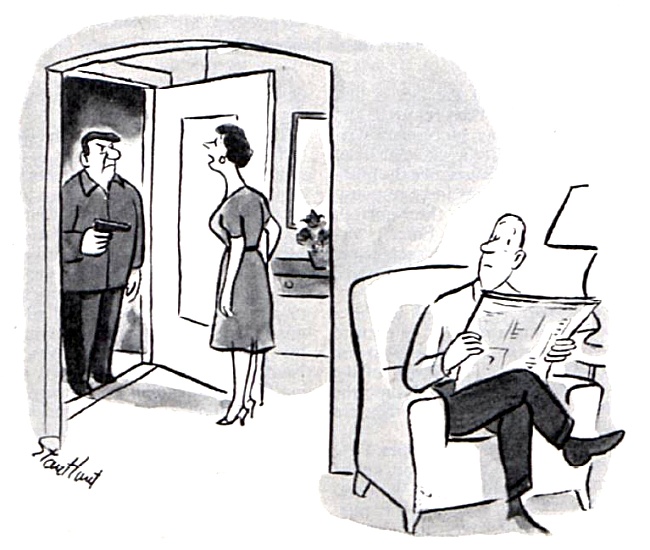

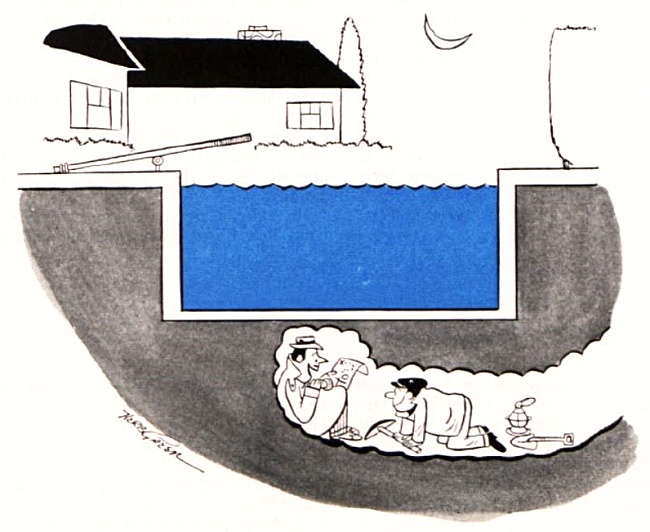

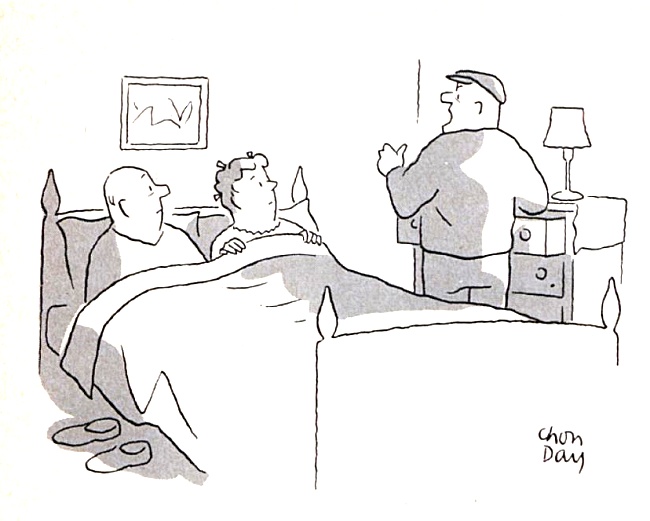

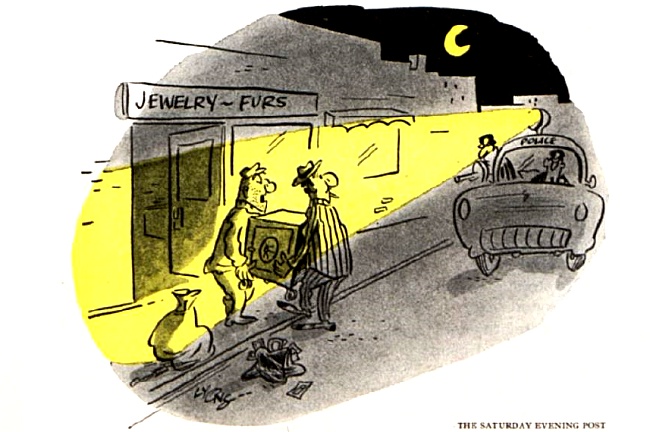

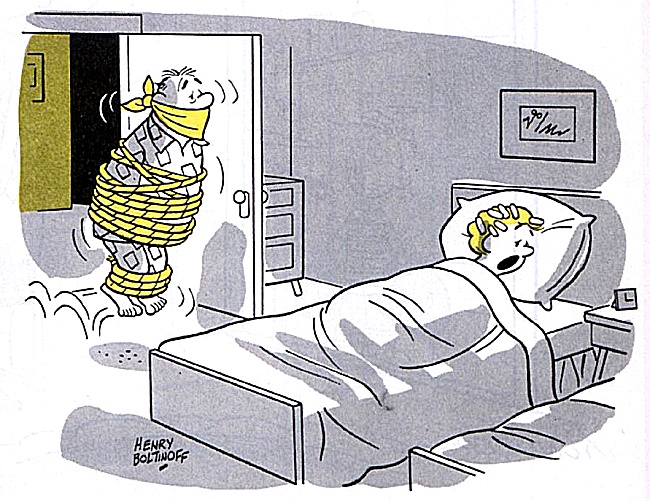

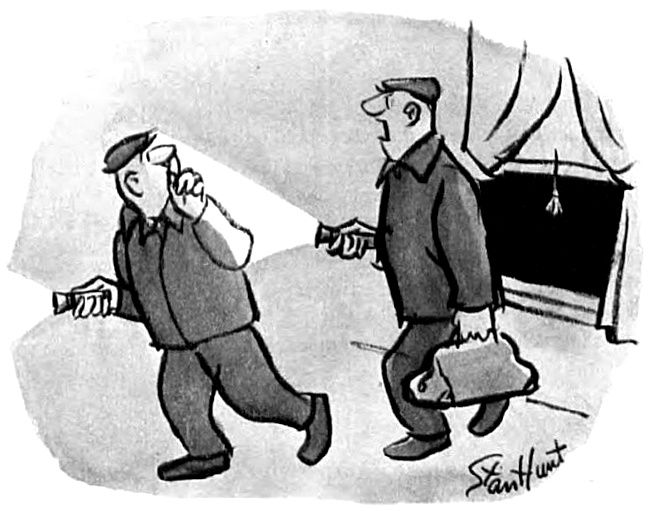

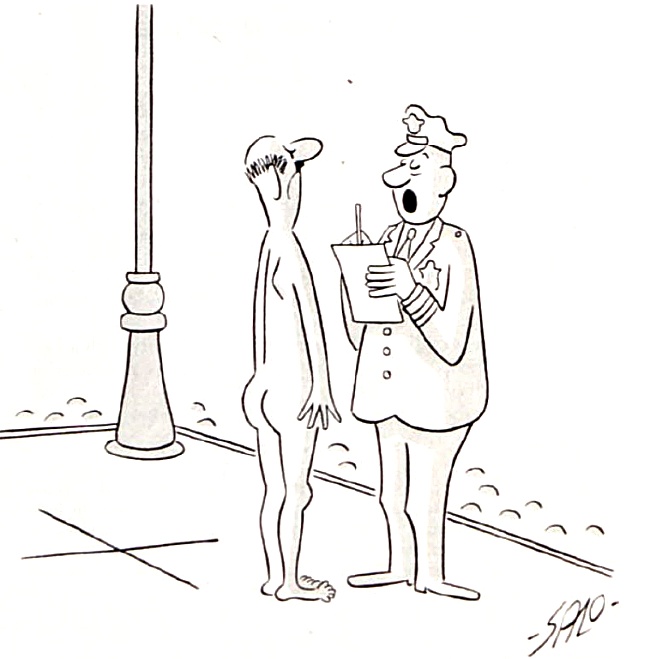

Cartoons: Burglar Banter

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives. Cc

Stan Hunt

August 5, 1961

John Gallagher

February 27, 1954

Herb Green

July 11, 1959

Chon Day

June 23, 1962

Harry Lyons

June 9, 1956

Henry Boltinoff

January 13, 1962

Stan Hunt

November 7, 1959

Salo Roth

September 24, 1960

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

The Young & the Restless: Five Facts at 50

After decades of enthralling regular viewers and easing countless school sick days, The Young and the Restless turns 50 this week. A titan of the daytime soap opera format and one of the few left standing on broadcast television, Y&R has endured with intricate, sometimes years-long storylines and the support of an ardent fanbase that has kept it atop the ratings longer than some of its current cast have been alive. Here are five big facts you should know about a CBS institution.

1. How It Started

The genesis of Y&R comes from a familiar television motivation: competition. In the early 1970s, ABC had achieved dominance with soaps that orbited younger characters (those being General Hospital, All My Children, and One Life to Live). CBS wanted a younger-skewing soap of its own. To that end, they tapped into the creativity of William J. “Bill” Bell and his wife, Lee Phillip Bell. Bill had been a radio writer and a protégé of Irna Phillips, who created, among other programs, Guiding Light, As the World Turns and Another World (another of her mentees, Agnes Nixon, would create All My Children, One Life to Live, and Loving). Lee had been a popular talk show host in Chicago, including a 30+ year run on the eponymous The Lee Phillip Show. Bill frequently incorporated the social issues that Lee covered on her show into the scripts that he was writing for Irna Phillips’s shows and other programs like Days of Our Lives.

Given the chance to create their own show, Bill and Lee followed the youth-oriented directive and came up with The Innocent Years. Upon further reflection, figuring that America wasn’t quite so innocent anymore, the show was renamed The Young and the Restless, which they figured captured the mood of early ’70s youth. Debuting in a half-hour format, the series went to a full hour in 1980.

2. That Familiar Theme

The Young and the Restless 50th Anniversary opening credits (Uploaded to YouTube by Soap Opera Moments)

The instantly recognizable Y&R theme is a piece called “Nadia’s Theme,” composed by Barry De Vorzon and Perry Botkin Jr. The two musicians have an incredible array of soundtrack work on their resumes, ranging across both film and television. De Vorzon co-wrote popular songs like “Big Rock Candy Mountain” and handled composing duties for films like Cooley High and The Warriors. Botkin did music for TV shows like Happy Days, worked as an arranger for the likes of Bobby Darin, and produced and arranged the massively influential Incredible Bongo Band version of “Apache,” samples of which became a cornerstone of hip-hop.

The pair initially wrote “Nadia’s Theme” as “Cotton’s Dream” for the 1971 film, Bless the Beasts and Children. “Cotton’s Dream” was subsequently chosen for the Y&R theme, but then the song took a strange turn. In the mid ’70s, the popularity of Romanian gymnast Nadia Comăneci was at a fever pitch. In the summer of 1976, ABC’s Wide World of Sports assembled a montage of her floor work set to “Cotton’s Dream” (which, ironically, she never used for floor exercise herself). The network was inundated with requests for the song. De Vorzon and Botkin rebranded the tune as “Nadia’s Theme,” and it was released as a single. In 1976, it hit #8 on the Billboard Hot 100. The song would earn a Grammy for Best Musical Arrangement.

3. Statistical Superlatives

It’s impossible to discuss Y&R without acknowledging its most amazing record. After steadily climbing in popularity through its first 16 years, the show hit #1 in the daytime drama ratings and has held that spot for the past 34 years. The show has been awarded the Daytime Emmy for Outstanding Drama Series 11 times. The series passed the 12,500 aired-episodes mark in May of 2022. Its spin-off, The Bold and the Beautiful, is one of the most popular daytime dramas in the world, airing in 110 countries.

Bill Bell’s run as head writer lasted from the show’s 1973 debut until he stepped down in 1998, making him one of the longest-tenured head writers in soaps. Bill and Lee also created something rather unusual in daytime: a family production legacy. Their oldest son, William Bell, Jr., operates the family’s production companies, Bell Dramatic Serial Company and Bell-Phillip Television Productions, Inc. Son Bradley Phillip Bell serves as Executive Producer and head writer for B&B. And their daughter, Lauralee Bell has played Christine “Cricket” Blair on Y&R since 1983.

4. Queens and Kings

The Young and the Restless has generated some of the most popular characters to ever appear on daytime. What’s more, many of the actors have served on the show for decades, or have frequently returned after breaks for other projects.

The zenith of that list has to be Jeanne Cooper, who played Katherine Chancellor from the show’s first year until her passing in 2013, a 40-year run. She was nominated for Outstanding Supporting Actress once and Outstanding Lead Actress at the Daytime Emmys nine times (winning once in 2008). Cooper’s performance raised the bar for all of the actors around her, and she’s been referred to as an icon by a number of publications and “the matriarch of all soaps” by publications like The Winnipeg Press. She has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and made history in 1984 by allowing her own face lift procedure to be filmed and incorporated in the show as a storyline for Katherine.

The show produced another queen of the genre in Melody Thomas Scott, who has played Nikki Reed Newman since 1979. Scott was nominated for Outstanding Lead Actress at the Daytime Emmys in 1999. Her storylines over time have been tightly tied to one of the leading men of the form: Eric Braeden, who plays Victor Newman. Scott and Braeden’s combustible chemistry lifted them to dominant characters on the series. Braeden himself won a Daytime Emmy for Lead Actor in 1998, and has been nominated eight times in total. Ironically, Braeden had been intended to be a one-note villain and killed off quickly, but Bill Bell loved the actor’s work so much that he instead focused on a much longer and more complicated character journey.

5. How They Started

Shemar Moore’s first scene on The Young and the Restless (Uploaded to YouTube by RestlessRick)

While Y&R has a vast cast, many of whom have been with the show for years, even decades, the series is also notable as a launch pad for actors that have had varied and successful careers in film and television after leaving the show. Among the big names that once walked Genoa City are Tom Selleck (the original Magnum, P.I.; Blue Bloods), Eva Longoria (Desperate Housewives), David Hasselhoff (Knight Rider; Baywatch), Shemar Moore (Criminal Minds; S.W.A.T.), Penn Badgley (Gossip Girl; You), Vivica A. Fox (Kill Bill; Independence Day), Justin Hartley (This Is Us), and the late Paul Walker (The Fast & Furious franchise).

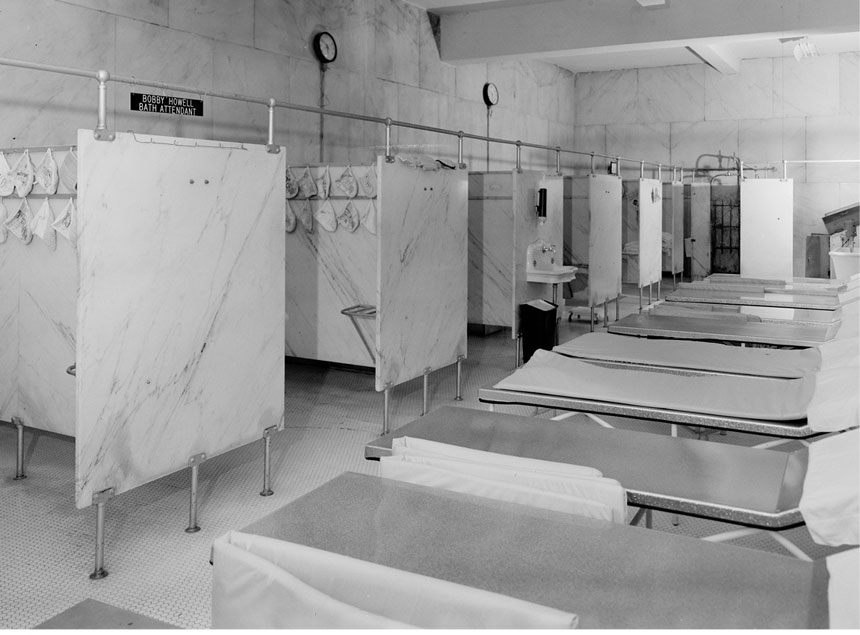

Tough Love at the Spa

Didn’t they give you a luffa?”

Tim, the manager of the spa at the Buckstaff Bathhouse in Hot Springs, Arkansas, is concerned. I am sitting in a comfy black leather chair in the men’s locker room — a splendid double-decked, blue-and-brass fantasia of lockers punctuated by a grand central stairway, a facility of such striking symmetry it could be the set of a Wes Anderson movie.

I’m here for the same menu of services that has been offered at Buckstaff for 111 years: A top-to-bottom, inside-and-out once-over that promises to restore my vigor and bolster my health. At about $80, it sounds like an unbeatable bargain.

But the balance of Tim’s universe is slightly off at this moment. It’s the luffa thing. I was supposed to get one when I checked in with the nice women at the front desk, a team that is apparently so steeped in precision they never, ever, forget to give a guest his luffa.

“You’re sure …” he persists.

I show him my empty hands, and Tim is forced to accept this aberration. He shows me to a dressing cubicle, with three metal lockers, and pulls the blue-and-white striped privacy curtain across.

“You can put your clothes in one of the lockers and put the key around your wrist,” he says. “I’ll go see if I can find you a luffa.”

I have to smile at the irony of the privacy curtain, because I am at this moment contemplating my most consequential decision of the day: Will I proceed with donning the bathing suit I’ve brought along, or will I engage in the time-honored tradition of this century-old spa and go forth into its white marble halls stark naked?

The world was a different place in 1912, when the Buckstaff Bathhouse opened along Hot Springs’ Bath House Row. If I were standing on this very spot 111 years ago, I would be surrounded by men wearing nothing but their handlebar mustaches, standing around speculating about the Kaiser’s plans, and perhaps engaging in a barbershop quartet rendition of “Come, Josephine, in My Flying Machine.”

I’ll not burden you with much detail as to why I’m choosing to go with the trunks. I actually came in here steeling myself for a nude adventure. In my relatively fit early years, I wouldn’t have thought twice. But I’m 67 now, and perhaps I spent too many formative years rushing through the crowded locker rooms at Jones Beach and Asbury Park and Bear Mountain, averting my eyes from the elderly gents who seemed so weirdly comfortable standing around, bodies sagging in the most alarming places, chatting idly about what’s up with Mickey Mantle, and do you think JFK has a chance against Nixon. I swore to my little self I would never join the ranks of those gravity- and weight-denying fellows, and I finally decide I’m not about to start now.

Tim escorts me out to the spa’s main room, an enormous space with a 20-foot ceiling and marble walls that reach all the way up. In the center is a fleet of blue cushioned cots; around the perimeter are lines of marble cubicles, about 12 of them, each home to an enormous 80-gallon ceramic-and-cast-iron clawfoot tub.

“This is Dave,” Tim says, introducing me to a healthy-looking fellow, seemingly about my age, in khakis and a white polo shirt. “He’ll be your spa attendant.”

It’s a little odd to hear the word spa attached to this sprawling space that, aesthetically at least, has more in common with a Walmart than Canyon Ranch. I was not expecting ferns and incense, but neither was I prepared for the stark utilitarian nature of this fluorescent-lit expanse. I find myself humming “White Room” by Cream — “where the shadows run from themselves.”

Again, I need to remind myself, I am here as something of a time traveler. In 1912, Hot Springs was not simply a vacation destination. This place was, in fact, something just short of a hospital. People came from around the nation to soak in the hot, soothing waters, to absorb the healing minerals, to relieve conditions modern medicine had not yet come close to easing.

Dave ushers me to one of those cubicles and invites me to slide into the tub. The water, a few inches deep, is already warm. He turns a spigot and in pours truly hot water, straight from the local earth, fed by gravity from the bowels of Hot Springs Mountain, located directly behind this building. Clear as a prism, the water that now embraces me fell from the sky some 4,000 years ago, then seeped through the mountain’s rocky crevices, heated to about 142 degrees in what amounts to a natural pressure cooker. A dial thermometer, manufactured by the long-defunct hydrotherapy company Ille Electric of Williamsport, Pennsylvania, registers my bath water at around 102 degrees.

Flicking a switch, Dave engages the water jet, a cylindrical blue device that resembles a tiny Evinrude outboard motor.

“Ten minutes,” Dave says.

He hands me my luffa. “Most of the guys use it as a pillow.”

Then he is gone, leaving me to contemplate the marble wall and the tips of my toes resting at the other end of the tub. Beyond my cubicle, I hear other jets in other tubs containing other men, churning away.

This is easily the largest bath tub I’ve ever sat in; I am practically swimming in it. For a moment, I am a little kid again, in my family’s big old cast-iron tub, sloshing around with the rim up around my eyes.

The traditional bathhouse treatment involves not settling in and letting the world slip by, but embarking on a station-to-station journey from one apparatus to the next. Having fetched me from my bath, Dave is now leading me toward a row of open booths containing more porcelain vessels, little brothers of the big tubs but more like large kitchen sinks, set on the floor.

“Sitz bath!” says Dave with what seems unwarranted enthusiasm. He takes my hand, helps ease me in butt-first — and leaves me there. Traditionally, this mini-soak is supposed to ease hemorrhoids and promote prostate and kidney health. Mentioned less often is the historical fact that the sitz bath is one of the chief reasons Chicago gangsters like Al Capone and Baby Face Nelson used to make the pilgrimage to Hot Springs. Soaking his nether regions in the supposedly therapeutic waters — into which judicious amounts of mercury were mixed — Capone hoped to reverse the ravages of the incurable syphilis that was swarming through his body.

It is hard to imagine a more humbling position than hunching, knees nearly to your chin, in four inches of hot water. You’ll see lots of historic images of men soaking in whirlpool tubs, sweating in saunas, and wincing through rigorous massages, but you will never, ever see photos of those same men indelicately squatting like fleshy frogs.

Every once in a while the knees of another client pass by. Reluctantly, but reflexively, I glance upward and see an equally embarrassed face looking down, like a big city pedestrian passing an unfortunate wretch, down on his luck, without even a proper pair of pants.

My mind wanders 111 years hence. Looking back from the 2200s, what present-day “healthy” practices will mystify our descendants? Peloton? Pickleball?

I’m desperate for something to look at. Something to read. But all that’s within sight are two signs, for unknown reasons posted right next to each other, bearing the same words: “10 Minute Limit in Sitz Bath.”

Dave’s khakis come into view. “All right!” he says, extending a hand. “Time for the steam room.” He pulls me from the sitz bath like a boatman hauling in a monkfish.

In the classic Victorian bathhouse scheme, the steam room is not the tile-lined, mist-filled chamber where movie mobsters meet to plot gang wars or the Sex and the City women dish gossip while barely staying wrapped in their towels. Dave gestures me into a contraption that is absolutely the stuff of 1950s sitcom dreams: The metal-doored, hole-in-the top steam cabinet, the thing you would imagine Lucy Ricardo or Ralph Kramden getting trapped in.

I sit on the wooden bench. Dave proceeds to seal me inside with the grand clanging of metal flaps. My head protruding from the top, I imagine I resemble a half-human, half-robot hybrid. Dave wraps my neck in a towel to prevent the soaking hot air — heated solely by the spring water — from escaping.

“We’re trying to bring your body temperature up to about 114 degrees,” he tells me, settling onto a bench barely within view. “The idea is to kill off any germs and viruses that might be susceptible to that kind of heat.”

If I were casting a movie about a bathhouse attendant, I would hire Dave the moment he came into the room. Steely-eyed and built like a retired high school gym teacher, he’s been pulling guys out of sitz baths here since the 1980s. And he seems to love his job, which makes the inevitable humblings of a day at the spa a lot more fun than they would ordinarily be.

If this were a Tex Avery cartoon, at the end of 10 minutes Dave would open the steam box and reveal my body shrunken and shriveled to the size of a large dried apricot. But as the lid is lifted and the relatively cool air wafts around my body, I feel unexpectedly invigorated.

Then I stand up and feel a slight wave of lightheadedness. That’s not unusual, and the next phase of my treatment will address that. Dave has me lie down on one of those blue cushioned cots and proceeds to wrap me in a thick, cool sheet. Comfortably papoosed, I’m told I’ll be lying like this for the next 15 minutes.

“Most of the guys go to sleep about now,” Dave tells me. “I’ll wake you when time’s up.”

But I don’t want to go to sleep. As interesting as all this is, I’m pretty sure this is going to be my one-and-only traditional spa experience. Like Aerosmith, I don’t want to close my eyes, ’cuz I don’t want to miss a thing. Despite creeping drowsiness, I virtually pry my eyelids open, taking in the patch of peeling ceiling paint and listening to the echoing sounds of gurgling whirlpool tubs, bodies plopping down into sitz baths, and flip-flops flapping against feet.

I think I was snoring when Dave began to unwrap me, like Lord Carnarvon tending to the mummy of King Tut.

“Okay!” he says. “That’s it for me. I’m gonna hand you over to Zan for your massage.”

From the wide-open spaces of the main room I am led to a warren of smaller ones. In one I find Zan waiting by a massage table. The surroundings are a jarring contrast to my previous massage experiences: I’ve been rubbed down to the sound of sitars on cruise ships and in an open-air cabana with a view of the volcanic cone of Bora Bora. Those locales are to this room what Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar is to a Winn-Dixie, but from the moment he lays hands on me it’s clear Zan means business in ways those fancy masseuses and masseurs never did.

A longtime sports massage therapist in Phoenix, Arizona, Zan came to Hot Springs to visit his girlfriend’s family and decided to stay. After a few relatively gentle preliminaries, Zan is soon folding my arms and legs into positions I’m pretty sure they have not assumed since I was swimming around in my mother’s womb.

Zan has me roll over onto my stomach. I stare at the floor, my face a cameo framed in a terry-cloth-padded oval. Like everything else here, the tile pattern below is strictly utilitarian; white and black with a squared-off flourish near the wall. As Zan punishes my upper back for its sins of inactivity, from another chamber I hear echoes of Hank Thompson wailing a long-ago song of countrified sorrow: “The only sanctuary I seek/Is on tap, in the can or in the bottle/Oh bartender bring it to me.” At the time this place was built, country music had barely descended from the hills and hollows of the Arkansas Ozarks. Now the air echoes with it as millionaires sing of battered pickup trucks they’ve never driven and shoeless childhoods that never were. As weird as this place may be, at least it’s stubbornly real.

My time is up. Zan leaves me as I slowly lift myself to a sitting position, my feet dangling off the table. I swing them lazily, wondering for a brief moment if, when I try to stand on them, they might just flop under me like overcooked fusilli.

I pad my way back to the locker room, past the grand tubs, past the humble sitz baths. Again, I try to imagine this place teeming with millionaires and gangsters, tended to by an army of attentive bath drawers, sheet wrappers, and body masseurs. I stop for a moment and listen for the voices of those naked men, echoing ever so faintly within these marble walls.

It wasn’t a better world, nor a simpler one. Just different.

“Hey!” It’s Dave, chasing after me. “Don’t forget your luffa!”

I weigh the spongy mitt in my hand. It comes home with me and now sits in my shower. And I still don’t know what it’s for.

Bill Newcott is a three-time International Regional Magazine Association Writer of the Year (2020-2022) and movie critic for The Saturday Evening Post.

This article appears in the March/April 2023 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Rockwell Video Minute: Swimming Hole

See all of the videos in our Rockwell Video Minute series.

News of the Week: Florida Blobs, Popular Dogs, and How to Make a Perfect Martini

Random Notes

If that blob of seaweed heading to Florida really is twice the width of the United States, maybe Disney could solidify it some way and build a new theme park on it, to get away from the political controversy down there.

It’s that time of year when I switch from drinking hot tea to something cold for the summer months. I know people who drink hot drinks during the summer but I’ve never understood that.

Every time a Wheel of Fortune contestant says during the interview portion of the show “my lovely wife of 10 years,” I think, wow, that’s pretty young to be married.

Hey Tommy Hilfiger: I like your leather belts but I shouldn’t almost slice my hand trying to get the plastic logo off of the buckle.

One of the great things about being my age is that you’re set in your ways and you know what you like and what you don’t like. It’s very comforting.

If you need another reason to avoid Twitter, there’s this.

The New Most Popular Dog Breed in the U.S. Is …

… the French Bulldog? How did that happen? It beat out the Labrador Retriever and Golden Retriever, which are usually more popular.

The least popular dogs are the English Foxhound, the Norwegian Lundehund, the Sloughi, and whatever that dog from Cujo was.

Peanuts Drawing on Antiques Roadshow

We’ve had a lot of Charles Schulz news here lately, and I’m not trying to turn this into a “Charles Schulz every week” column, but here’s something else I saw the other day: An Antiques Roadshow “dog and cats” episode had a woman who brought in an original Peanuts strip that Schulz had given her father back in 1965. How much is it worth now? Take a look:

Uploaded to YouTube by Antiques Roadshow PBS

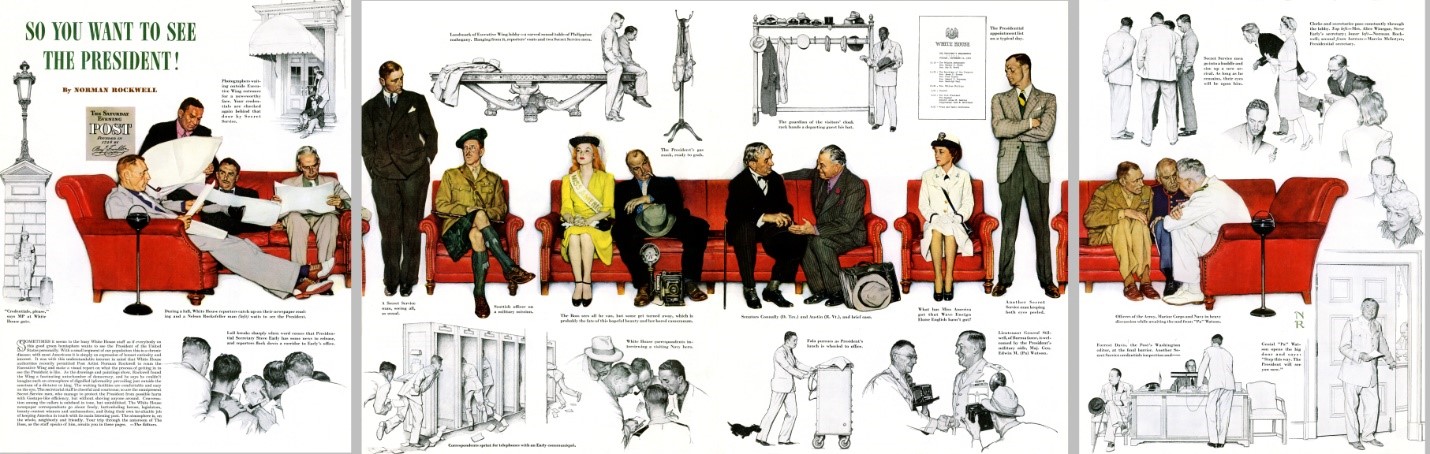

Lawsuit #1: Norman Rockwell Paintings in White House

Here’s something that will be of interest to Post readers. Family members of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s press secretary say that Norman Rockwell drawings that they owned were stolen years ago and loaned to the White House to hide them from the rest of the family! It’s a complex case that sounds like it would make for a great episode of Perry Mason.

Lawsuit #2: Are Boneless Wings Really Wings?

This doesn’t sound as important as the above case, but a man in Chicago has filed a class-action lawsuit claiming that the “boneless wings” served at Buffalo Wild Wings are not “wings” at all.

Quote of the Week

“My cats are gonna hate me.”

– The Price is Right contestant after losing a game

RIP Lance Reddick, Jim Gordon, Willis Reed, Stuart Hodes, Peter Hardy, Peter Werner, and Gloria Dea

Lance Reddick was a prolific actor who appeared in such TV shows as The Wire, Bosch, Fringe, Lost, Oz, and Law & Order: SVU. On the big screen he was in the John Wick films (the latest of which comes out today), Godzilla vs. Kong, and Jonah Hex. He also did voice work for cartoons and video games. He died last week at the age of 60.

Jim Gordon played drums on several classic songs, including the Eric Clapton/Derek and the Dominos hit “Layla,” Maria Muldaur’s “Midnight at the Oasis,” and the Mason Williams instrumental hit “Classical Gas.” He also played on such well-known albums as The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, Steely Dan’s Pretzel Logic, and Harry Nilsson’s Nilsson Schmilsson. He also played with Frank Zappa, Traffic, Alice Cooper, and many others. He died last week at the age of 77.

Willis Reed helped the New York Knicks win two championships in the 1970s. He’s a member of the Hall of Fame and his jersey number was the first to be retired by the Knicks. He died this week at the age of 80.

Stuart Hodes was an acclaimed dancer who performed with Martha Graham for years and then went on to be a choreographer and teacher. He was still performing into his 90’s. He died last week at the age of 98.

Peter Hardy was an Australian actor who starred in such shows as McLeod’s Daughters and Neighbours and the movie Chopper. He died last weekend at the age of 66.

Peter Werner won an Oscar for directing the 1976 short film In the Region of Ice and also directed episodes of Moonlighting, Justified, Medium, Ghost Whisperer, and Law & Order: SVU, as well as the terrific made-for-TV film Aunt Mary. He died Tuesday at the age of 76.

Gloria Dea was the first magician to perform in Las Vegas, in the 1940s. As an actress she appeared in Plan 9 from Outer Space, An American in Paris, Singin’ in the Rain, and other films. She died Saturday at the age of 100.

This Week in History

Grover Cleveland Born (March 18, 1837)

He’s still the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms in the White House and the only one to get married while in office.

Beatles’ First Album, Please Please Me, Released (March 22, 1963)

Many Beatles songs are classics of course, but it’s amazing that one single debut album can contain songs like “I Saw Her Standing There,” Please Please Me,” “Love Me Do,” “P.S. I Love You,” “Do You Want to Know a Secret,” and “Twist and Shout.”

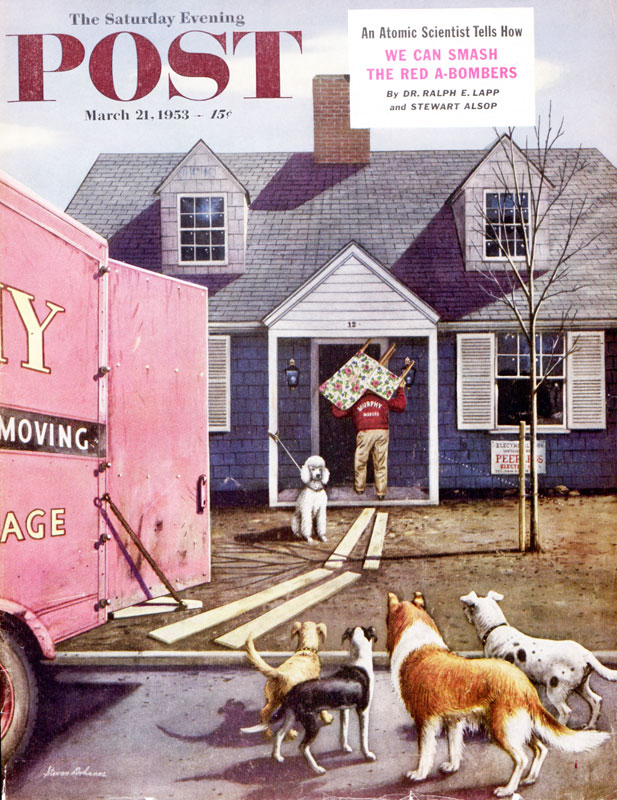

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: “New Dog in Town” (March 21, 1953)

There are no French Bulldogs in this Stevan Dohanos illustration.

Today is National Cocktail Day

If you plan it correctly, every day can be a cocktail day!

Here’s how to make a Classic Martini (with gin, because that’s the way I like them), and here’s how to make a Gibson. You’ve probably never heard of a Paper Plane, but give it a shot. And everyone who makes cocktails should know how to make an Aviation, a Negroni, and a Manhattan.

And, yes, there’s one called the French Bulldog and one called a Snoopy.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

Feast of the Annunciation (March 25)

I couldn’t have given you a definition of this day before I read Wikipedia’s, which says it “commemorates the visit of the archangel Gabriel to the Virgin Mary, during which he informed her that she would be the mother of Jesus Christ, Son of God.”

World Backup Day (March 31)

This is the day to backup all of your important computer files (but really, you should be doing that more than one day a year).

Tucker’s Story

Light flashed across the windshield as Jon Peterson pulled his silver BMW sedan slantwise into an open parking space. He turned off the engine and checked his watch. Six minutes to three. Climbing stiffly out of the car, he turned to take in the town he had driven two days to reach.