February, and cold, dead straw from the tall pines in the boxy yard had nearly covered the assorted junk and trash. Humps of brown straw like fire ant beds, and there were many of those too. The old man suspected that before long the searing ants might devour him and the boy both and there would be only chalky bones piled in the wheelchair where he sat with a .22-caliber pistol next to his right leg, like a life-saving device, bones on the stoop steps where the boy mostly sat, waiting like his mother told him for her to come back.

When Vera Arnold lit out for Orlando, towing her Airstream travel trailer behind her pickup truck, she took with her the best of her bad furniture and all her clothes. What she left in and around the small-frame rental house between the no-towns of Mayday and Statenville, in Southeast Georgia, 20 or so miles from the Florida line, was mostly junk. Junk, and her lame father and her 13-year-old son Butch, supposedly left behind to see to the needs of the rundown old man. The plan, according to Vera, was that she would get a job, get a house, and be back before you could say, “liar, liar, pants on fire.”

That was over a year ago, summer of 1998, and for all the old man and the boy knew, she may have hooked up with another mean man, her pattern, or been killed in an automobile accident, drunk — another weakness of Vera’s.

She’d been going for a long time and now she was gone.

The old man knew better than to expect her back, though, and the boy must have figured it out by then. Because gradually, throughout the winter, when the school bus let him out at the entrance ramp of the empty-looking green house, he had taken to wandering the woods and even the heavily trafficked highway butting the front yard. It would not have surprised the old man if one of those evenings his grandson didn’t come home at all. The old man had left his own makeshift home, hitchhiking, when he was 15; and for twice that many years he would hop a freight train when the notion struck him, and he couldn’t even claim that he wanted to see the world or be out on his own, only that some itch would take hold and the only way to scratch it was to go. Even after he stayed in Tupelo, Mississippi, maybe a year longer than he should have — he took a wife, fathered a child during that time — he left for parts unknown to them, wishing them well but doing little else to help keep them safe and fed. He left Louann, a plain but resourceful country girl, with a child, waiting, married but with no husband. Duty was what other people did, duty was for the timekeepers of the world, the steady drifters from day to day, from job to home and back again.

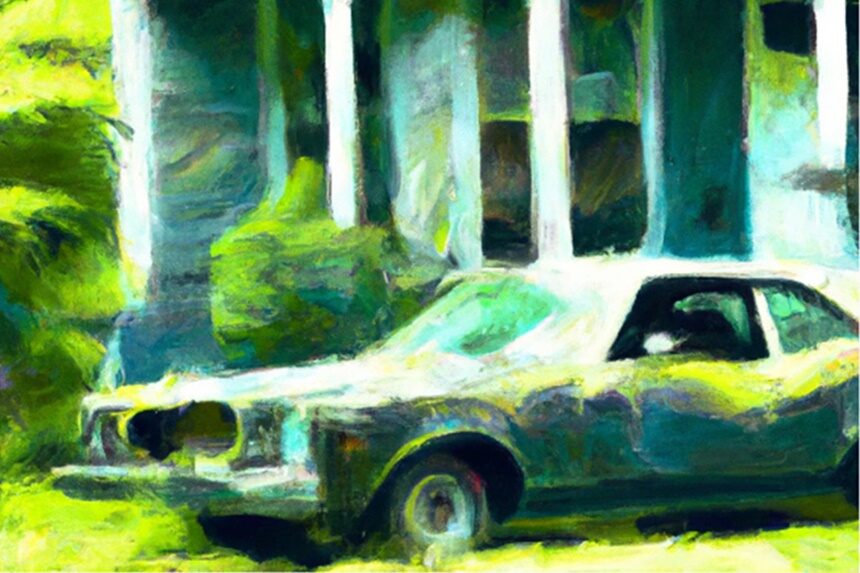

Butch was different, but still his mother’s son. The likeness to his mother was becoming more and more apparent: snapping off, sassing. The welfare lady, who kept them in groceries and medicine and heating fuel, had noticed too. Her advice to the old man was to demand that Butch stay busy, do chores. Starting with raking the yard and disposing of the trashed glass, paper, tires and what-have-you. Not much you could do with the rusted-out monster hulk of a car, Vera’s third husband’s Chrysler, blocking the old man’s view of the Walmart convoys on the northeast corner of the yard.

The pale old man on the stoop, in his wheelchair, pistol couched close to his leg, was long-bodied with gray hair cut close on the sides, the hair of a convict, he often thought, shaking his head with disgust when he looked in the mirror. He watched the boy raking pine straw into small piles. Stopping now and then to roll a tire over to the car, to toss a rusty wrench or a cracked side mirror toward the car. All other junk and trash he pitched over into the pine and palmetto boundary, the woods belonging to the owner who rented them the house.

How many times had Ray Moss threatened to evict the “sorry white trash” from the house? The old man had lost track. When he had run out of checks, the old man figured his money had run out too, and he had contacted the welfare. His last call before the black phone, transferred from table to floor, had been disconnected.

The boy used to pretend he was talking to somebody, replacing the receiver carefully on the hook when he was done. Then he started absently slinging the receiver by the stretched cord, like a tether ball. Something to do while he daydreamed, while he schemed.

Butch had grown a foot taller, it seemed to his grandfather, since his mother left. His hair had grown too, down to his shoulders. But that was by choice, not hormones or happenstance. Short and chunky when Vera left, he was now long and lanky, in skinny recycled blue jeans and silver-and-navy football jacket — the church in Mayday kept him in shoes and clothes. The old man too. New plaid flannel and fleece-lined bedroom slippers he wouldn’t have been caught dead in before the nerves in his legs started dying and his work boots became mere accessories. But beggars couldn’t be choosers, right? He had said that often and clear to the boy raking the yard now with a red bandana folded and tied around his forehead and knotted in back.

Car parts were now piled around the front of the old Chrysler, and the boy stood looking down at them. He picked up what looked to the old man like a tire tool and began prizing up the hood. It flipped up about an inch, shrieking metal. Then he slung the tire tool to the raked patch of yard, hove up on the hood, and began gazing down inside at the gluttonous engine.

One of the church ladies passed on the highway in her small blue car, heading south toward Statenville and the Florida line. The old man had thought about telling her and the others from church that he’d been baptized in the Mississippi River and look where his transformation had gotten him. When he’d told the boy, he had laughed about that — the first time he’d laughed at anything his old grandpappy had to say, and the old man regretted having reverted back to his old ways, but had been happy that the boy might be warming up to him.

If Vera ever came back, at least the two could be buddies. They could get along. Instead the old man was put in the position of nagger, when Vera might have saved the relationship by coming home and taking on her rightful role as nagger. All teenagers have to have a nagger, and that’s what the old man resented most. He used to hold the boy in his wheelchair, on his lap, smelling the unique oil of his light brown hair, while he sucked his thumb until he fell asleep.

Butch’s arms were high over his head, hanging to the raised hood with both hands, peering at the motor of the Chrysler, yard forgotten.

“Butch!” the old man called from the stoop. He felt the length of the pistol warmed by his leg, thinking it should feel cold instead.

The boy dropped his right arm and flashed his grandfather a look. Then he strolled over and picked up his rake and began raking again. Small piles to show he didn’t intend to take much more, small piles to keep from stressing those knotty muscles the old man had caught him flexing before the tall mirror behind the front door, the mirror like some escape hatch he’d just discovered in the house.

Mad now, the boy raked his way toward the ramp leading from the highway to the yard, windrowing pine straw. He had left the hood of the Chrysler up and the old man couldn’t see the Walmart semi coming till it was right on them. Day and night the trucks thundered and roared. When he looked back at the boy, he was wearing only his dingy white T-shirt, and his blue-and-silver football jacket was spread out on the dirt near the ditch, arms out as if it had flown there.

* * *

The jacket would become a common sight to the old man. It would replace the boy, day after day, when he got the Chrysler running, long about summer. The jacket would become symbol and the most longed-to-reach object of the grandfather’s invalid life.

If only he could get to the jacket, if only he could pick it up, if only, if only …

He sat on the stoop, swatting at mosquitoes, day after day, while the boy went riding on what had to be stolen gas. He smelled beer on the boy’s breath, when he did come in, beer mingling with that dirty hair the man had once loved to smell. He was a stranger. The grandfather no longer nagged, not even about picking up the jacket in the yard. Instead he told the boy how proud he was of him for reassembling the car’s engine and keeping it running. He wouldn’t mind going for a ride himself, he said, and meant it (also he’d like to get some clues to where the boy got his money and where he spent most of his time). The boy had only grunted and headed out the door.

The first time Butch slept out front in his car, his grandfather figured it was because he was too drunk to make it inside — he’d done that himself many, many times, back in Tupelo, Mississippi. In spite of the radio blaring, drowning out the sounds of katydids and the mysterious soughing of the pines, breeze or no breeze — the old man thanked God that the boy was safe, that he hadn’t been killed in a car wreck.

But when the boy slept in the car two nights running, the old man knew he had moved out for good. When the boy began backing the Chrysler up to the front wall of the house, close as he could get without dozing down the front wall, the old man figured the boy was in trouble and on the lookout for the law, or he had stolen a license plate.

One morning he woke to the heavy spatter-patter of rain on the tin roof. He rolled over and looked out the window and saw the Chrysler backed up to the house as usual, the rear end wedged into the corner by the stoop, and the roof of the car draped in filmy clear plastic sheeting. Either the windows had been broken out or would no longer roll up.

He scooted to the other side of the bed and reached for the pistol in the seat of his wheelchair, and like some ordinary morning ritual he placed the barrel inside his mouth, finger on the trigger and ready to pull. The metal of the pistol tasted of salt from his hands and minerals, of unwelcome cold. Not today, not yet — they’d had no rain for weeks, and he didn’t want to miss this rain. He placed the pistol back in the seat, then maneuvered his dead legs off the side of the bed next to his wheelchair, then hoisted himself into the sagged blue vinyl seat and arranged the cold pistol by his right leg. This could be the day.

The house was dim, an almost greenish light shedding through the dusty screens of the open windows. The pine flooring beneath the windows was swollen and speckled with mildew from the rain and damp. Somewhere there was an orange, already in the winey stage of rot. The smell of urine in the narrow hallway, from the bathroom, seemed even more familiar than the orange. So far, he had managed to feed and even sponge bathe himself but for the life of him he couldn’t get a true aim on the toilet bowl. The Black woman sent by the welfare to clean every two weeks never went inside the moldy, reeking bathroom, and he didn’t blame her. He would have liked for her to wash up his few dishes rather than just rinse and drain them, though. But beggars can’t be choosers, right?

After he added to the yellow puddle around the pedestal of the filthy toilet, he wheeled out and up the narrow hall to the kitchen, really only an ell off the living room to the left of the open front door. He took the small dull aluminum boiler from the drainer in the sink, rinsed and filled it with water, and set it on the stove and turned the knob till the blue flame whooshed and flared under the pot. Smell of gas, mingling with the mold and rotted orange he couldn’t seem to locate anywhere.

While the water boiled, he took his old white coffee mug from the drainer and spooned instant coffee into it. In the good old days when he was a man, he had loved a good cup of black brewed coffee. But he’d grown used to this murky branch-water with a head of foam like beer from the tap, which he’d loved too. He considered the tradeoff of brewed coffee for instant as part and parcel of his diminished life.

Hot cup of coffee in his left hand, he wheeled through the little empty living room, kicking the dead black phone out of his way, then out the open door to the stoop. He always left the door open for the boy regardless; he left the light on in the kitchen too because it didn’t matter either. He used to worry about things such as the light bill; he used to worry about rotting oranges and piss on the floor. He used to worry about being a shiftless beggar, but none of that mattered anymore.

Out on the stoop, he could feel the spatter of rain from the long trunk of the Chrysler wedged between the stoop and the front wall. It felt good after the heat of the night, after the long dry spell. The air smelled clean, of dampened dust. The rain was ticking on the plastic draped over the car. He couldn’t see inside, but he could hear that the radio wasn’t playing for once. And he took it for a good sign that maybe the boy was growing weary of the weird rock music, or maybe he had found peace in the clockwork-ticking of the rain the same as he himself did.

What the old man had in mind was to wait till the boy woke up and got out of the car to remove the plastic sheeting. He would say, Good morning. Or, We sure needed this rain. Something light like that to show Butch that he would no longer be nagging, that he understood. Because for a fact, the nagging did little good, was as pointless as looking for the orange or cutting down on electricity. Besides, to use his useless self as example was ludicrous. Actually it came to the old man, in the way of the coffee thing, now waiting for the boy to wake up and watching his blue-and-silver football jacket, centerpiece of a mud puddle, that he was being forced at last to look at his own sorry and wasted youth by watching the boy’s youth played out before him. God was punishing him for all his snapping back and sassing by making him sit still and alone so that he could do nothing but watch. And listen. And wait.

He would tell the world that waiting is to living what not-breathing is to the body. He would like to quit both. But if he quit now, he’d be bailing out on the boy same as his mother had. If he quit now, he might miss witnessing something good to come out of his existence on earth, maybe some turning point for the boy.

By the time he’d gotten cured of his going itch and returned home to Mississippi, Louann was dead and his daughter was a grown woman, twice divorced, with a boy of her own. It had been the old man’s intention to make up for all the suffering he’d caused his family by pitching in and helping his daughter make a living and raise her boy. It hadn’t worked out that way though, and before long he was having trouble with his legs — mere niggling crawling sensations at first. He was working at a garage, mechanicking, when he began to feel his legs give way, completely unable to control them. They would just give way without warning and he would be flat of his back or on his side on the concrete shop floor. Once he blacked out after hitting his head and had to be carted off to a hospital — another first for him.

Suddenly the plastic began sliding over the roof of the car toward the driver’s window, the end whipping inside and the wet crinkling corrupted by the crowing of the huge engine and the radio, a corruption of the rainy calm and the melty feel of the old man’s belated reckoning.

* * *

On the stoop again, later that evening, the old man sat following his nap. The sun had come out, and with it the mosquitoes.

The jacket in the puddle was crusted with mud and pine needles. Tiny sulfur butterflies swarmed over it and lit, suckling from its salt.

Not as much traffic on Sunday as on weekdays, the highway steamed, developing into low-level and drifting fog. Soft fog to a walking man. The old man’s favorite church lady passed in her red pickup and waved. A friendly woman with a bit of an accent, maybe a northerner — he couldn’t tell. But definitely not Southern and definitely not local and judgmental like many of the others. The old man laid his own judgment of them to his guilty conscience. He listened to the truck’s smooth engine fade out to a whine and wondered what would happen if he waved her down one Sunday to go with her to church. Had she meant the invitation? Would she still be as friendly if he took her up on her invitation by the time she went through the business of loading up him and his wheelchair? Suppose he got in church and had to go to the restroom; he had to pee about every 30 minutes here lately. Suppose he wet the floor of the church restroom.

He fingered the pistol by his right leg.

No, he wouldn’t go.

But he would like to.

He would like to make up for being a drunken rambler and judgmental himself. He would like to hear the singing and just to be with friendly people. He would like to give the boy a Mayberry Day: simple living and kind people. He used to love watching The Andy Griffith Show on TV, before Vera took not only the set but the boy’s innocence away.

Truth was, he was sitting out on the stoop waiting to die and not for Vera to come back for him and the boy.

He was just about to go inside, just about to go on to bed, though it wasn’t dark and even seemed because of the late sunshine as if the day was starting over. Another punishment — double days to get through all alone. He had already backed his wheelchair to the threshold of the door when he saw something red flashing along the highway behind the northeast corner blind of pines.

In a minute, he saw that it was Butch’s red bandana and that he was on foot, running along the edge of the highway. Not fast and not frantic, meaning nobody was after him, the old man hoped. In one hand was a blue can of beer — could be Busch, the old man’s favorite kind when he had a favorite kind.

Loping up the weedy ditch to the yard and its hillocks of sodden pine straw he’d raked months ago, the boy broke from a run to a walk, spying the old man on the stoop with his hands at ready on his chair wheels.

He could hear the boy breathing hard as he reached the stoop steps, turned and sat and slugged down the rest of the beer. He set the can next to his right leg and placed his elbows on his knees and hung his head so that his light brown hair parted, revealing his tender trenched nape.

“It quit.” He looked up and out at a passing white pickup. “It just up and quit on me.”

“I hate that,” the old man said, unmoving.

“Do you?”

“I do. Maybe it’s out of gas. Maybe it’s the bat’try.”

The boy picked up the beer can and crushed it between his hands. He seemed to be staring out at his jacket on the ground, now abandoned by the butterflies too. “Ain’t out of gas and ain’t the bat’try.”

“You hungry?”

“Yep. Hungry for a beer. You got one?” He snorted, laughed. Sat there. Quit laughing. Then, “She ain’t coming back, is she?”

“I don’t look for her to, no.” The old man thought it was kind of nice, the two of them just sitting there talking. Honestly talking, for once.

“What about us? Me and you?”

“Well, the way I figure it, even if she was here, even if she had come back, you’d be old enough by now to be practically on your own anyway.”

“What about you?”

“Fact is, I’d’ve checked out a while back, hadn’t been for you.”

The boy turned, only his head. His eyes flared and he looked white around his nostrils and mouth. He laughed. “Man, you can’t even walk, much less hit the highway.”

The old man didn’t answer.

“Oh!” the boy finally said, staring out again at the yard filling in with grains of darkness. “I been thinking about quitting school and going in the Navy.”

“Could be the making of you; that’s what they say.”

Butch hung his head again, shaking it. “No, man. I ain’t leaving you.”

“They’s places for old men like me, you know.”

“You mean an old folks’ home, right?”

“Could be. Could be I’d stay right here like I been doing. I make out all right.”

“I ain’t much help, am I?”

“No. But I figured I could call on you if I fell or something.”

Both quiet, they listened to the bellowing of frogs and the seesawing ringing of the katydids.

“I don’t hate her no more,” Butch said. “Do you?”

“Never did. But it amounted to about the same thing.”

“Grandpa, you don’t reckon she died, do you?”

“Naw. You know Vera.”

“I don’t want to be like her, Grandpa. I don’t wanta be the kind to just up and take off … leave somebody.”

“You won’t be. I don’t think you will.”

The boy stood and walked off through the dark of the yard. The old man lost sight of him but could hear him shaking something he figured was the jacket. Grains of sand falling on the overgrown grass and sifting through. In a minute he saw the boy come walking back, holding the jacket out from his body by his side.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Janice Daugharty paints a picture, with her beautiful writing, of melancholy and grief for what could have been. I couldn’t help but feel for this dejected and pitiful grandfather. Reading this, I wished for so much more for both of the characters and felt frustrated in the cycle of generational trauma. I found myself hoping that somehow the grandson would break that cycle with better choices and not repeat his family’s mistakes.

Not an easy story to read Ms. Daugherty, but very well written and descriptive to be sure. This physically challenged and traumatized grandfather with his grandson basically doing the best they can under very difficult circumstances life’s thrown at them. Time is getting short for grandpa, hopefully Butch will fare better with some good breaks.

The Chrysler is one of the characters too, which is unusual in itself. From the painting (initially) I thought it was a ’73-’75 Chevelle from the door forward on the side, with a broken grill upfront. Now I know it’s a ’75-’77 Cordoba, the only Chrysler that ever looked anything like the one pictured.