This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

It’s unquestionably true that many historical figures have challenged gender norms and binaries in ways that our histories often fail to appreciate. Defining and categorizing the identities of historical figures is at best a fraught and partial process, and one about which we must be careful and thoughtful. But as we begin a Pride Month when transgender Americans are under widespread and sustained attack — as are all LGBTQ+ Americans, but the trans community in particular ways to be sure — it’s especially important to recognize that transgender people have been present in every period of American history and community. Here I’ll share just a handful of examples from across the last 200 years.

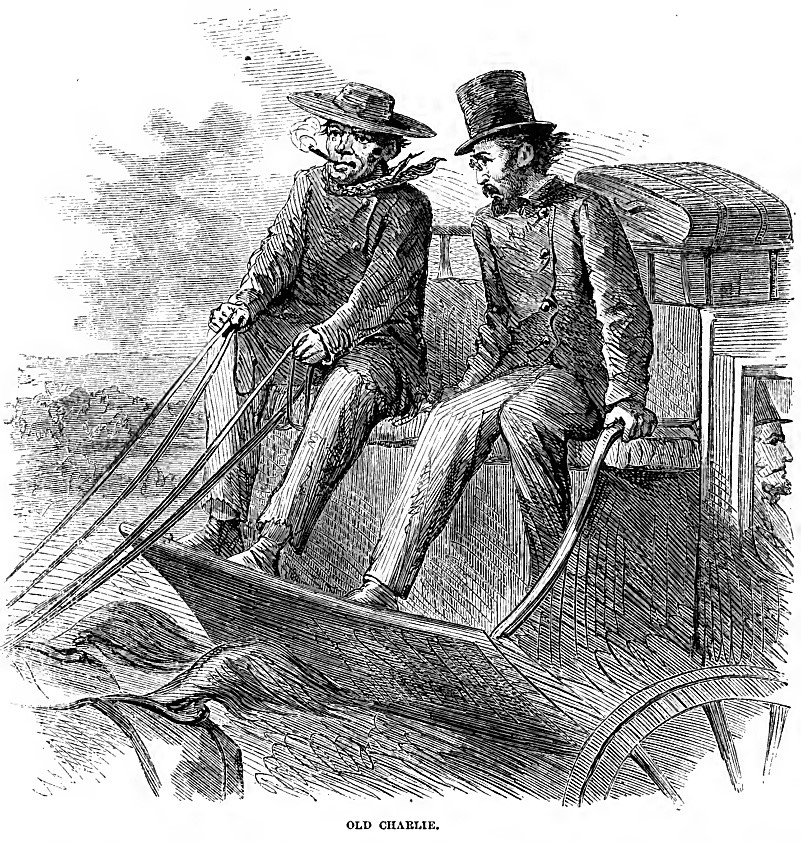

Charley Parkhurst (1812-1879) was born Charlotte Parkhurst in Vermont but would create a new identity for himself as one of the American West’s most famous stagecoach drivers in and after the Gold Rush era. Orphaned as a very young child, Parkhurst apparently began to adopt a male name and presentation in a New Hampshire orphanage, and as a teenager ran away and found work in a Rhode Island livery stable. When the Gold Rush hit, Parkhurst traveled West like so many other Americans, taking work as a stagecoach driver and horse wrangler in California, losing an eye to a horse’s kick (from which he gained the evocative nickname “One Eyed Charley”), and becoming well known for riding some of the area’s most dangerous mail and delivery routes. Only upon Parkhurst’s death in 1879 was his birth gender discovered, as illustrated by an 1880 New York Times obituary headlined “Thirty Years in Disguise: A Noted Old Californian Stage-Driver Discovered after Death to be a Woman.”

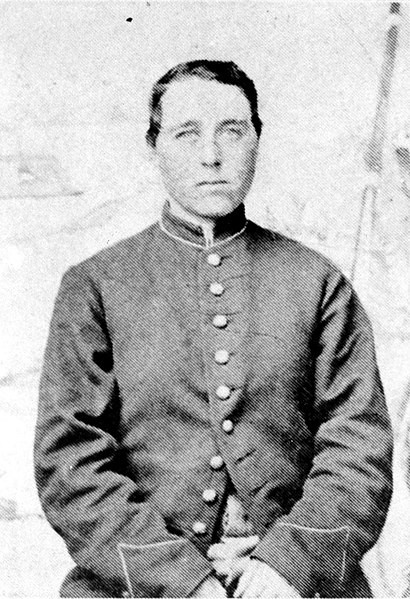

If the West offered one space where individuals like Parkhurst could challenge gender binaries and create new identities, service in the Civil War offered another, if even more dangerous, such opportunity. Of the many women who took on male identities to serve in that conflict, one whose story particularly echoes Parkhurst’s was Albert D .J. Cashier (1843-1915). Born Jennie Hodgers in Ireland, Cashier likely first adopted a male identity to work as a teenager in an Illinois shoe factory. But it was in order to enlist in the 95th Illinois Infantry in August 1862 that an 18-year-old Cashier is first known to have used that name, and it was under that name and male identity that Cashier lived the remaining half-century of his life after the war’s end. Cashier became a fixture in his small town of Saunemin, Illinois, working numerous odd jobs, drawing a veteran’s pension, and even voting in town elections for decades. Even his tombstone initially read simply “Albert D .J. Cashier, Co. G, 95 Ill. Inf.”; it was his executors who eventually tracked down his Irish birth and began to piece together the stages and shifts in Cashier’s life and identity.

While some trans individuals like Parkhurst and Cashier found spaces and communities where they could seemingly live comfortably as their most authentic selves, others like Lucy Hicks Anderson (1886-1954) faced far more overt prejudice and oppression. Born male to the African American Lawson family in Waddy, Kentucky, she rejected that gender identity from a very young age, renaming herself Lucy; local doctors encouraged her parents to let her dress in women’s clothes and live as a girl. At a young age Lucy moved West, first to New Mexico where she married Clarence Hicks and worked as a chef, then (after divorcing Hicks) to Oxnard, California where she opened a saloon and brothel, became one of the area’s most prominent socialites, and married a young soldier named Reuben Anderson. But when her brothel was investigated during World War II she was discovered to have been born male and was charged with perjury for having lied on her marriage license. Despite her claims at trial that “I have lived, dressed, acted just what I am, a woman,” she was found guilty and sentenced to serve in a man’s prison. After her release the Oxnard police chief barred her from returning to town, and she and Reuben moved to Los Angeles, where Lucy died not long after.

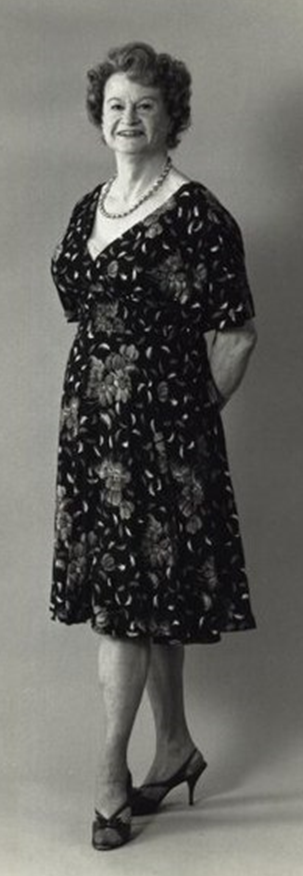

Another prominent Californian, Virginia Charles Prince (1912-2009), took some of the 20th century’s most significant steps in defense of trans individuals and communities. Born Arnold Lowman to a wealthy Los Angeles family, Prince began dressing and privately identifying as a girl as a teenager, but continued to live publicly as a male through at least the early 1940s, receiving a Ph.D. in pharmacology and marrying a woman with whom they had a son. When Prince’s continued cross-dressing led to a divorce a few years later, she began to research and write more extensively about transvestism and related topics, culminating in 1960 with her creation of the groundbreaking magazine Transvestia. Through both the research she gathered there and her own articles — such as her 1967 essay, “The Expression of Femininity in the Male” — Prince offered vital resources and support for fellow transvestite and transgender individuals.

She also created an organization to offer community for those individuals, the Foundation for Personality Expression (later known as the Society for the Second Self). Prince lived well into the 21st century, and so was able to see many of the social change and progress to which her work certainly contributed.

One of the most significant such changes for transgender individuals was the possibility and availability of sex reassignment surgery. The first American to become well known for undergoing that medical procedure was the World War II veteran turned actress, singer, and activist, Christine Jorgensen (1926-1989). Born George William Jorgensen in the Bronx, Jorgensen was drafted into the military at the age of 19; it was upon returning to New York that she learned of sex reassignment surgery and began pursuing it. Unable to elect the surgery in the United States despite years of attempts, she eventually traveled to Denmark to do so, and it was when she returned to New York that she was outed by a December 1952 New York Daily News story headlined “Ex-GI Becomes Blonde Beauty.”

Jorgensen leaned into this publicity to both tell her own story and advocate for fellow transgender Americans: through autobiographical writing like her February 1953 American Weekly essay “The Story of My Life”; through working as an actress and recording artist, often in costume as Wonder Woman (which she changed to her own invented character of Superwoman when Warner threatened a lawsuit); and through speaking tours of universities and other communities. In a Los Angeles Times interview published just a year before her death, Jorgensen noted, “I am very proud now, looking back, that I was on that street corner 36 years ago when a movement started. It was the sexual revolution that was going to start with or without me. We may not have started it, but we gave it a good swift kick in the pants.”

This Pride Month, it’s clear that the revolution needs to continue, in our historical awareness and our contemporary politics alike. The stories of trans Americans from across our history can help give us all those necessary kicks in the pants.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now