This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

A couple weeks back, the legendary TV game show Jeopardy! celebrated its 60th anniversary. Jeopardy! has gone through a number of iterations since its March 30, 1964, debut episode, with the most well known being the 1984 primetime reboot, which aired nightly and was hosted by Alex Trebek. The original version, hosted by Art Fleming, was a weekly show that aired during the day. The origin of Jeopardy! is strikingly linked to a key moment in game show and American history.

As Jeopardy! creator Merv Griffin shared in a 1963 profile while the show was still in development, “My wife Julann just came up with the idea one day when we were in a plane bringing us back to New York City from Duluth. I was mulling over game show ideas, when she noted that there had not been a successful ‘question and answer’ game on the air since the quiz show scandals. Why not do a switch, and give the answers to the contestant and let them come up with the question?”

That inverted format certainly did make Jeopardy! stand out and has no doubt contributed to its longevity, helping produce one of the most iconic game shows of all time. Those late 1950s “quiz show scandals” not only inspired Julann Griffin’s idea for Jeopardy! but also have the most to tell us about this genre and American history in the mid-20th century.

As TV quiz shows developed from the late 1930s through their 1940s growth and into their 1950s heyday, they also consistently revealed the tensions inherent in the genre of the game show. Those tensions are illustrated by the genre’s name itself: These are indeed games, with rules and results and winners and losers and so on; but they are also shows, designed to entertain and appeal to audiences (and needing to do so in order to maintain ratings and stay on the air, of course).

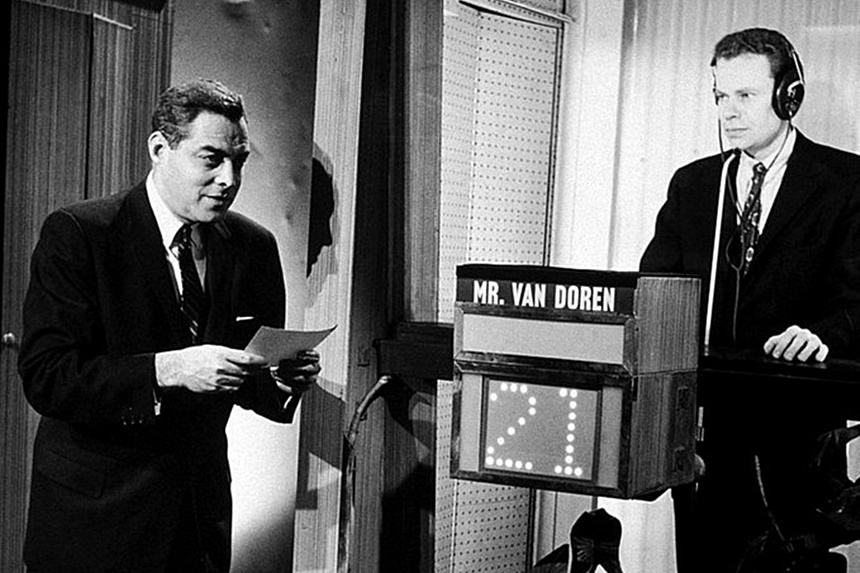

One of the first and most prominent quiz show fixing scandals began as a direct result of that tension. The September 1956 debut episode of the NBC quiz show Twenty-One (hosted by Jack Barry) went quite poorly, as the two contestants got most of the questions wrong; the show’s main sponsor, Geritol, complained to the network about this uninteresting product, and producer Dan Enright demanded a change. Just a couple months later Twenty-One featured an extended run of victories by Herb Stempel, the contestant who would later raise the initial accusations of fixing, both on his behalf so he would win and then later, when the producers decided the throw Stempel over in favor of a more handsome contestant, on Charles Van Doren’s behalf.

If these scandals were thus very much about entertainment, the responses to them quickly and thoroughly became about something very different: the law. When a fixing scandal for a second game show, Dotto, emerged in August 1958 (as the Twenty-One scandal was also really breaking), the result was nothing short of a nine-month-long New York County grand jury investigation, in the course of which a number of producers and contestants apparently committed perjury rather than admit to their roles in the scandals. The grand jury did not ultimately hand down indictments, but the whole thing then escalated even further, to an August 1959 U.S. Congress subcommittee investigation. That investigation did produce a significant and enduring legal change, a 1960 amendment to the influential Communications Act of 1934 that made fixing game shows illegal.

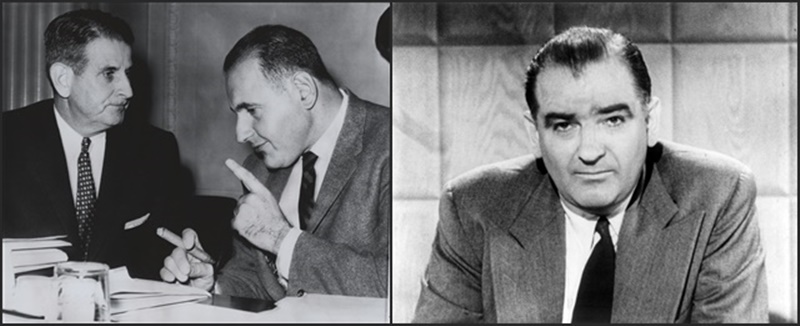

The scandal’s escalation to Congress was particularly telling, as it echoed the subcommittee investigations and hearings that had dominated the U.S. government in the Cold War’s early decades. While those McCarthy-era hearings were of course linked to fears of Soviet communism, they were also very much centered on questions of truth and trust, which applied to the entertainment industry as much as the political realm. The implicit danger of the quiz show scandals was that they would further undermine the public’s trust and sense of what was true. The Congressional hearings for the scandals were thus not only a response to those questions of truth and trust, but an attempt to reassert that (despite the thorough fall of McCarthy by this time) the federal government could continue to be an arbiter of that truth and trust.

Quiz Show (1994), the Robert Redford-directed film that features the Twenty-One scandal in particular, certainly engages with all these 1950s themes. But the film focuses even more on another aspect of the scandal, a more ambiguous but also a more definingly American one: the role that identity played for individual figures like the Jewish underdog Stempel (played in the film by John Turturro) and WASP son of privilege Van Doren (played by Ralph Fiennes). Some of the most prominent targets of those Cold War Congressional investigations, after all, were Jewish Americans, many facing direct, bigoted accusations of “dual loyalty.” Stempel’s ultimate vindication as a necessary whistleblower on the people who were truly betraying the public trust can’t be separated from those complex 1950s contexts.

The final lesson from the quiz show scandals is the most universal, but also the most important: a lesson about our shared humanity. When we watch game shows, it isn’t always easy to remember that each and every contestant (and even the host) is a complicated human being, with all the baggage of heritage, family, community, psychology, and more that influence and shape each of us. Which makes it that much more important that we remind ourselves of this shared humanity, not just of the quiz show scandal figures but of everyone who takes part in the tradition of TV game shows or, for that matter, life in America.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now