This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

In late March, Alabama became the latest state to pass a wide-ranging law seeking to ban Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion (DEI) programs and the teaching of “divisive concepts” in its public schools and institutions. The bill features a number of specific elements, including a requirement that public universities “designate restrooms on the basic of biological sex…as stated on the individual’s original birth certificate.” But it also reflects another step in the seemingly nationwide push to challenge, limit, and even ban entirely the teaching of our hardest histories to students of all ages.

It will come as no surprise to readers of this column that I vehemently oppose those efforts, for reasons that extend far beyond knowledge. One goal of history education is to provide students with both broad and deep knowledge of all the subjects that they’re encountering. But to my mind, an even more important goal of history education is the creation of empathy, providing students (and all of us) with the opportunities and skills to truly connect with and understand what their fellow Americans have experienced, in particular concerning our hardest histories.

In this August 2019 column, I wrote about my first visit to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History & Culture (NMAAHC) and about one particularly striking exhibit in that important space: Emmett Till’s casket. There’s no doubt that standing before that casket elicits complex and powerful emotions and makes it impossible for visitors not to sympathize with Mamie Till, her family, and her community’s experiences of our most violent and painful past. The NMAAHC offers many opportunities for genuine awareness, understanding, and sympathy — all prerequisites for empathy.

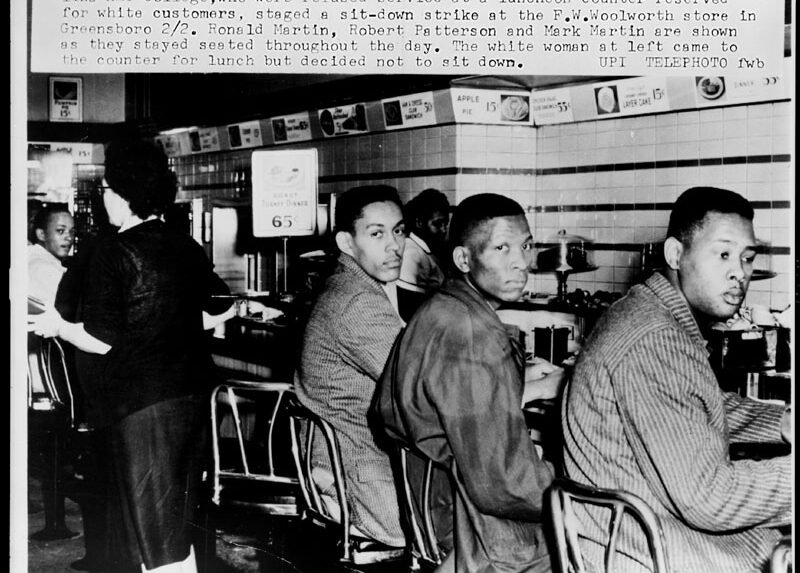

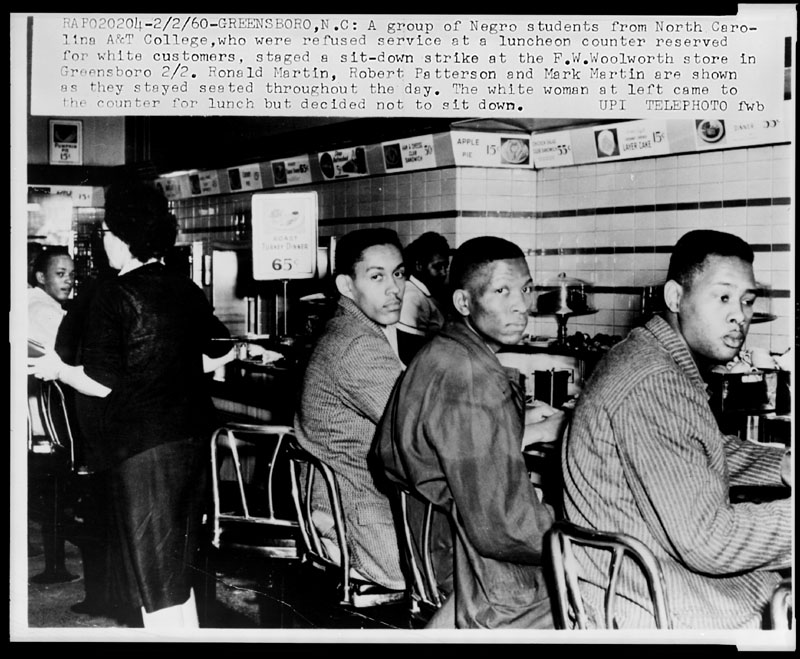

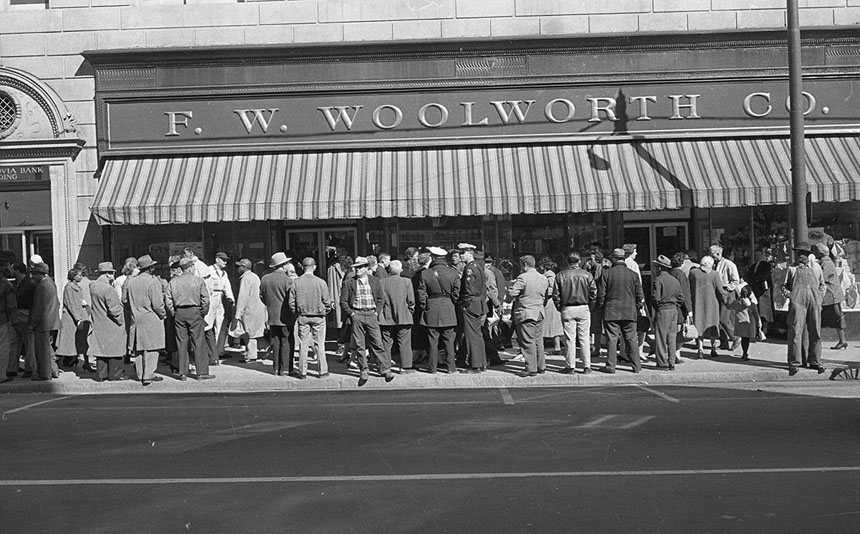

I recently had the chance to visit a museum and exhibit that excelled in creating empathy for another of our most challenging national moments. While visiting Atlanta’s impressive National Center for Civil and Human Rights, I took part in a special exhibit focused on the civil rights movement’s lunch counter sit-ins. After guiding visitors through a series of informative displays about the sit-ins, the exhibit culminates in a unique interactive experience: Visitors sit at a recreated lunch counter, put on headphones, and find themselves awash in the sounds and sensations that actual sit-in participants experienced in 1960 (building to an increasingly hostile and violent series of responses from racist rioters).

As an American Studies scholar I was already aware of many of the stories that the exhibit includes, and I believe I had even heard recordings (or at least seen video footage) of the attacks on sit-in participants. But this immersive exhibit connected me to those events far more completely and compellingly than had any of those prior experiences. The exhibit asks visitors to see how long they can listen to the recording before they need a break; I was initially skeptical of that premise, but with my eyes closed I genuinely found it difficult to endure even two minutes of the hate and violence that these courageous activists dealt with for far longer. I came away from the experience with a significantly deepened and more empathetic perspective on those individuals and these histories alike.

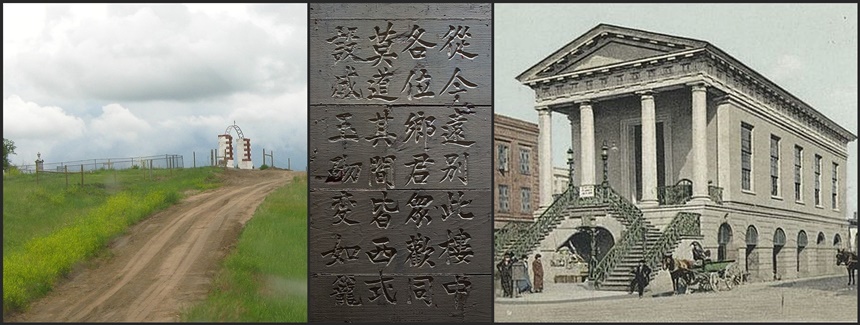

Museums and other historic sites offer one excellent type of opportunity for creating such empathy. Sitting in one of the holding cells at California’s Angel Island State Park, seeing the preserved poetry carved into the walls by immigrants detained at the island’s immigration station for months and years. Walking the grounds of South Dakota’s Wounded Knee Massacre Monument on a wintry day, imagining the onslaught of violence from the U.S. soldiers yet also the ghost dance and community those forces could not extinguish. Stepping inside the doors of Charleston’s Old Slave Mart and seeing the cavernous and intimidating space that held the fate of so many enslaved people upon their first arrival to the continent. Those and many other sites across the country help visitors empathize with our difficult past.

Yet classrooms have their own vital role to play in offering opportunities for understanding and empathy. In Zora Neale Hurston’s novel Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), her narrator Janey argues that “You got to go there to know there.” Most of the time students cannot physically go to the places about which they’re learning, but they can still immerse themselves in the perspectives of their fellow Americans. To cite just one example: In a striking early moment in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845), he writes, “My feet have been so cracked with the frost, that the pen with which I am writing might be laid in the gashes.” I know of no line of writing that more potently pushes its readers to empathize with the physical and emotional tolls of enslavement.

One of the most consistent rationales given for the current spate of anti-education efforts has been that teaching these “divisive concepts” makes students feel “uncomfortable.” While that might be one potential effect (and not necessarily a bad one), the deeper and more vital truth is that teaching our hardest histories, in and out of the classroom, is a crucial step to helping us all feel for our fellow Americans, past and present.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now