This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On February 19th we commemorated a sad anniversary: the 72nd anniversary of President Franklin Roosevelt signing Executive Order 9066, the proclamation that created the federal policy of Japanese American incarceration. We now have a new collective space that can help us remember and understand that divisive and painful period: Amache National Historic Site, the newest addition to the roster of national historical parks operated by the National Park Service. President Biden designated Amache as a National Historic Site in March 2022, and its status was formally finalized this past week.

Our national parks features a wide variety of sites, many of which are quite celebratory in their overall presentation — Concord’s Minute Man National Historical Park is a good example. But an important subset, like Amache National Historic Site, seeks instead to grapple with our darker moments, and offers suggestions for how we the people can do the same.

The national park system itself offers a potent example of our more complicated histories, as many of our most prominent Parks occupy land that was taken from (and in many cases sacred to) indigenous communities. In her book Saving Yellowstone: Exploration and Preservation in Reconstruction America (2022), for example, historian Megan Kate Nelson traces how that famous Park was carved out of Lakota Sioux homelands. And at least one National Park, Colorado’s Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site, is dedicated to commemorating both indigenous homelands and the violence through which those communities were displaced.

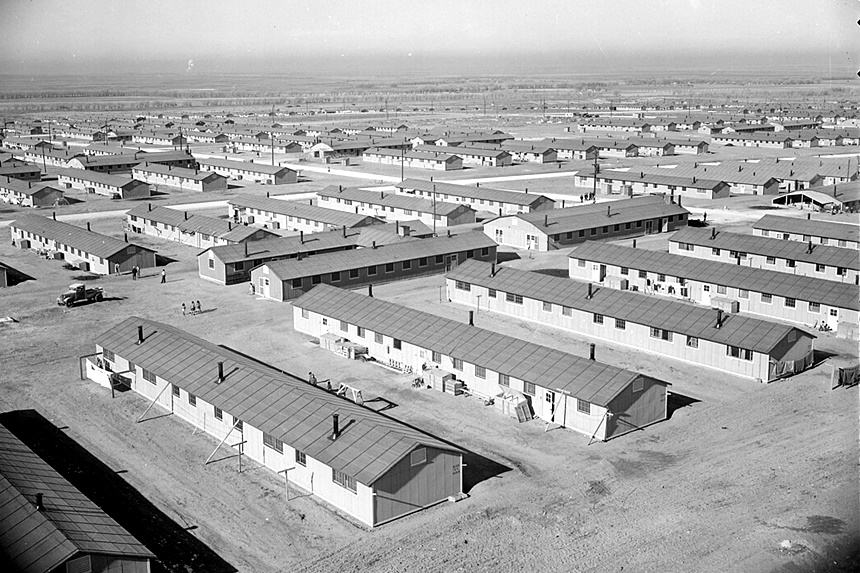

Other national historical parks commemorate even more directly the displacement of American communities onto their lands. The newly minted Amache National Historic Site is just one of a trio of National Parks focused on Japanese incarceration, joining Manzanar National Historic Site in California and Minidoka National Historic Site in Idaho. Each of these sites is distinct, but all of them feature both preservations and re-creations of the harsh environments and spare accommodations in which their Japanese American prisoners lived for years.

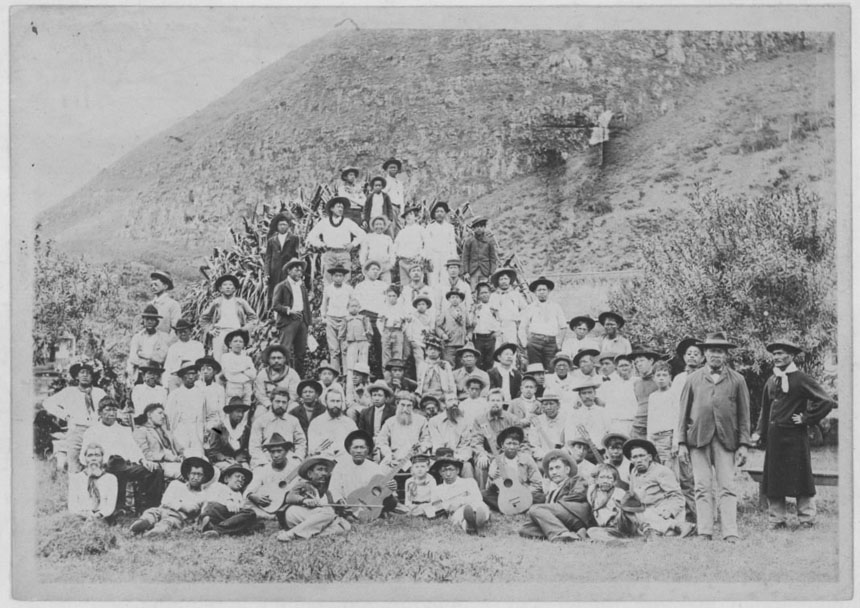

Occupying a very different physical landscape but likewise a site of imprisonment is Hawai’i’s Kalaupapa National Historical Park, where thousands of people suffering from leprosy have been banished and died since the 1860s. As at the Japanese incarceration sites, Kalaupapa’s preserved historic buildings help us understand what it truly meant to be sent to and isolated in this place.

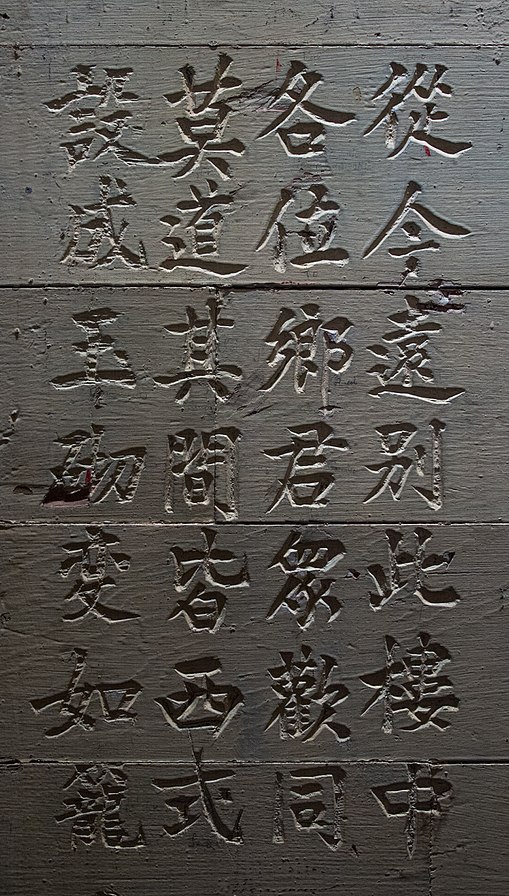

It’s a California state park rather than a national park, but I can’t highlight preserved sites of imprisonment without mentioning Angel Island State Park in San Francisco Bay. Many of the thousands of Chinese Americans and other Asian Americans imprisoned for months or even years at Angel Island Immigration Station during the Chinese Exclusion era carved poems and other inscriptions into the walls of their cells, and many of those texts have been preserved along with the state park’s historic buildings. The park allows us quite literally to encounter the voices of those affected by it.

Americans have been imprisoned for many reasons throughout the centuries, and another national park, Georgia’s Andersonville National Historic Site, offers another history of incarceration. Roughly 45,000 Union prisoners were held at Andersonville during the Civil War, and nearly 13,000 of them had died by the war’s end and were buried at the neighboring cemetery (now part of the site). Besides the preserved facilities and environment, the Andersonville Historic Site also features extensive and searchable documentation of those prisoners of war, offering a powerful glimpse into the individual lives as well as families and communities affected by this prison’s horrors.

Sites that are far less overtly horrific than prisons can still feature painful histories, of course, and some of our more celebratory National Historical Parks likewise can show us those darker sides, as illustrated by the evolution of two prominent Massachusetts sites. In recent years Salem Maritime National Historic Site, long focused on that city’s history of shipping and trade, has expanded its commemoration of the Triangle Trade, the broader system of global commerce and colonialism which inextricably linked Salem with slavery throughout the Western Hemisphere. And similarly, Lowell National Historical Park, which focuses on a re-creation of the city’s textile mills, which transformed industry and America alike, has added exhibits that trace the mills’ interconnections with cotton and slavery, as well as the anti-slavery activists who sought to challenge and change those practices.

There are also National Parks that commemorate individuals and communities who helped push the nation closer to its ideals. New York’s Harriet Tubman National Historical Park captures not just the home and story of that inspiring individual, but also communities like the Thompson AME Zion Church that Tubman helped build. Complementing that site is Maryland’s Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park, which documents that anti-slavery network through both Tubman and this local setting and across North America. And in Arkansas, the Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site preserves a very different but equally inspiring space of communal resistance, one in which nine African American students who integrated that school and their families and allies fought the forces of segregation and racism and helped change education and America.

Every space can become a classroom for our hardest shared histories, and our national parks offer a wide and impressive variety of such settings.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now