It’s Quieter in the Twilight

⭐️ ⭐️ ⭐️

Run Time: 1 hour 23 minutes

Documentary

Director: Billy Miossi

Streaming on Amazon Instant Video, Apple iTunes, and Vudu

Decades before COVID-19 changed everything, there was already a dedicated staff of scientists who’d perfected remote working, to the extreme: As they clicked away at their computer keyboards, their two “offices” were speeding away from them at 38,000 miles per hour.

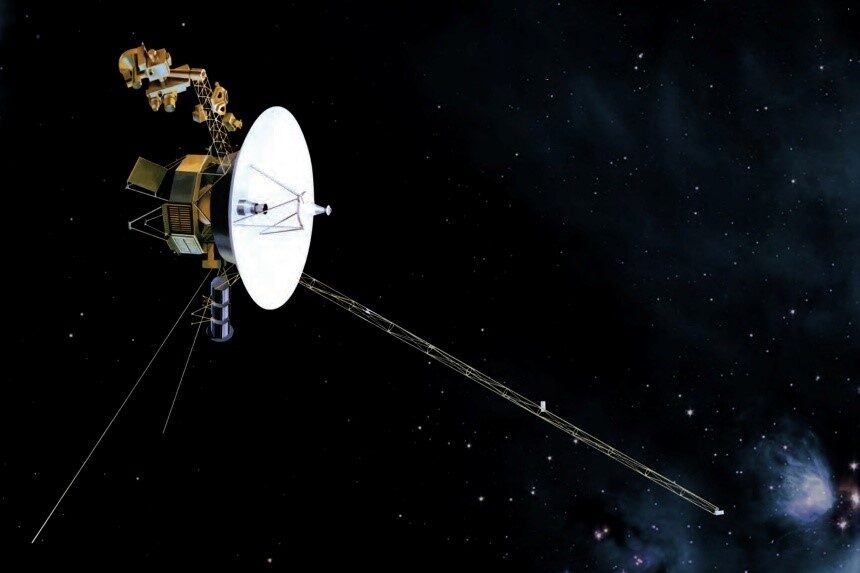

Today, nearly 50 years after NASA’s twin Voyager spacecraft were launched to explore the outer regions of the solar system and beyond, a skeleton crew still sits at those screens, cups of coffee in hand, checking in daily with the two home offices — which at last count were nearly 15 billion miles from Earth.

Some of them have been there nearly from the start.

It’s Quieter in the Twilight, director Billy Miossi’s affectionate chronicle of the Voyagers and their human caretakers, seeks out the staff of a dozen or so persons (down from thousands in the project’s 1980s heyday) toiling away at a paneled office in an Altadena, California, strip mall. The year is 2019. Now pretty much an afterthought, the Voyager mission has long since been evicted from the plush Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, a few miles away, and ensconced in what looks like the domain of a down-on-his-luck chiropractor.

But, against all odds, the plucky Voyager crafts insist on creating new science. In the past decade, both of them have pushed beyond the outermost reaches of the sun’s solar wind — defining for the first time just how big our solar envelope really is—and now are transmitting data from the immeasurable expanse of interstellar space.

Project scientist Edward Stone has been there from the beginning. In archival news footage, we see him as NASA’s Voyager frontman, leading press conferences and triumphantly announcing new space exploration breakthroughs.

And here Stone is 50 years later — the only project scientist Voyager ever had — thumbing through the new data, discovering hidden scientific gems culled from signals beamed across the cosmos from a spacecraft operating on less power than it takes to light the bulb in your refrigerator. (Stone did finally retire in October of 2022.)

As remarkable as the continuing accomplishments of the Voyagers are, it is the human element that makes It’s Quieter in the Twilight compelling. Suzanne Dodd worked as a low-level scientist during the Voyagers’ early days, then moved on to other NASA projects. When, decades later, she was invited to become the program’s final project manager, her response was: “Really? Voyager is still happening?”

The day-to-day work of the Voyager team is reminiscent of that old car mechanic just outside of town who still knows how to adjust a carburetor. As the probes’ nuclear fuel steadily decays, the experts devise ingenious ways to make do, shutting down little-used onboard devices and shifting voltage back and forth between the few that are still running — pecking away on keyboards attached to computer monitors that resemble those of Commodore VIC-20s.

Faced with the news that the world’s only antenna that can communicate with Voyager 2 is going to be shut down for a year, the team scrambles to create and upload a series of long-term programs that will keep the space probe operating throughout the period of radio silence. That’s a tough enough assignment; compounding it is the reality that, even traveling at the speed of light, each simple computer command takes up to 20 hours to reach the spacecraft — and it will be another 20 hours before the scientists learn if the command actually worked.

Listening for those whispers from the cosmos are an appealingly nerdy team of space geeks, some of them having spent their entire careers nursing the spacecraft. Among the veterans is Mexico-born power subsystem manager Enrique Medina, who came to the U.S. on vacation in 1968 and decided to stay after he met the woman he’d marry. He started working as an engineer on the Voyager project in 1986.

Fernando Peralta recalls being overwhelmed by the sight of Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the moon and deciding then and there to become part of the U.S. space program — this, despite the fact that he lived in Bogotá, Columbia. Moving to the U.S. with his young family, he found work in demolition while taking aerospace engineering courses at the University of Texas. A visit to JPL led, almost inexplicably, to a job offer: To join the team assigned to the then-decade-old Voyagers.

Sun King Matsumoto, born in South Korea, joined the team in 1985. At home, we find her in the kitchen with her grown son, proudly displaying a Lego Voyager he built as a child.

“When he calls, he asks me, ‘How is Voyager?’” she says. “Like he’s asking, ‘How is Grandma?’”

Like doctors tending to patients on life support, the Voyager team is slowly watching their patients’ vital organs fail. One morning, they know, they will come to work, transmit a digital “Good morning” across the Solar System — and get only silence in return.

As they sit before Miossi’s patient and compassionate camera, it is a prospect that moves more than one of them to tears.

“But we’ll be here,” project manager Dobbs tells the filmmaker. “Just as long as Voyager needs us.”

And until then, Medina adds solemnly, “You don’t want to let Voyager down.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now