Were these illustrators for the Post caught robbing a bank?

These gentlemen with their arms raised, caught in a searchlight, are some of the top illustrators who worked for The Saturday Evening Post (from the left: Frank Reilly, Arthur William Brown, Gilbert Bundy, Harry Beckhoff, and John Gannam). Some were rascals and some were rogues, but none of them were bank robbers. Instead, they were posing as gangsters for a 1947 painting by their good friend, the artist Dean Cornwell, who was known as “The Dean of Illustrators.”

Today the internet makes it easy for artists to find reference photos of models in every conceivable pose or costume. But in the golden age of illustration, artists pitched in to help each other, and had a lot of fun doing it. The fiction that appeared in the Post was often colorful, romantic, and exciting, so coming up with models, costumes, and props for the stories could be a challenge. For example, when Post illustrator Austin Briggs had to draw futuristic characters wearing spandex space outfits, he and his wife would pose in their underwear in the backyard. They stood on their “space ship,” the battered old family picnic table.

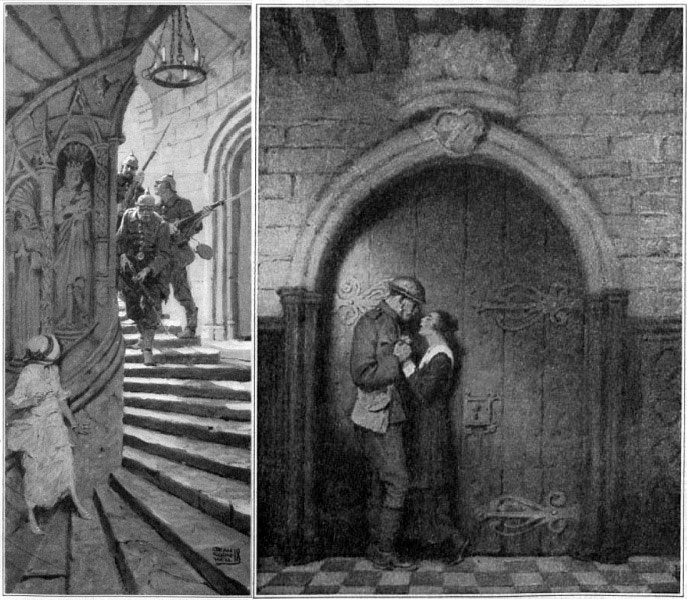

Cornwell was one of America’s greatest illustrators, famous for his moody, romantic paintings. He created over 1,000 illustrations for stories by top authors such as Ernest Hemingway, W. Somerset Maugham, and Pearl Buck.

It took a special kind of imagination to bring such stories to life. Illustrators were not like academic painters who were content to paint flowers or bowls of fruit; they tended to be more colorful types.

Like many of his “rascal and rogue” illustrator friends, Cornwell’s creative spirit was spawned by an unconventional life. He was born in 1892 in Louisville, Kentucky. His childhood was cut short at age 13 when his father was severely injured in a street car accident. This turned Cornwell into the “man of the house,” and what a house it was. As a result of his head injury, Cornwell’s father experienced severe hallucinations, making home life unpredictable and riotous. Conditions became so untenable that the family committed the father to a mental institution. In order to support his family in his father’s absence, Cornwell left school at age 16 to work as a trumpet player and drummer on a Mississippi riverboat. There he experienced a great deal of life. But the bee fertilizes the flower it robs: Cornwell would later become famous for his beautiful paintings of riverboats.

At the age of 19, Cornwell landed in Chicago where he resolved to get serious about a career in art. He enrolled in classes at the Art Institute of Chicago and found work as an artist for two Chicago newspapers, the Chicago Tribune and the Chicago American. Working for newspapers, he gained practical experience drawing cartoons and spot illustrations for news articles and advertisements. When his work for newspapers slowed down, he took on work designing window displays for the large department store Marshall Fields, and hand lettered signs for several other stores. Cornwell had learned to be a survivor.

In 1914 when he turned 21, Cornwell received his first assignment as a real illustrator: to create three illustrations for a story to appear in Redbook magazine, entitled, “When The Devil Was Sick.” In 1916, his illustrations first appeared in The Saturday Evening Post.

Cornwell’s career was interrupted by the Great War in 1917. When he registered with his draft board, he listed his employment as “illustrator for The Saturday Evening Post.” After the war, Cornwell developed into a hugely popular illustrator, working regularly for magazines such as Redbook and Cosmopolitan. His eye for beauty was not limited to paintings on canvas. He loved the pretty girls associated with the illustration business and developed a reputation as something of a philanderer. He went through more than one marriage, while having affairs with some of his beautiful models. As described in Cornwell’s biography, The Art of Dean Cornwell written by Daniel Zimmmer, Cornwell wrote an article professing his innocence, entitled “We Are Not Sheiks.” Cornwell argued that he and his fellow illustrators were really very chaste, despite their proximity to nude models. He wrote, “I feel that someone ought to try to correct the mistaken impression the public seems to have about us artists.” Nobody seemed convinced, especially Cornwell’s wives.

With his newfound wealth and fame, Cornwell was able to travel extensively, painting the scenes wherever he went. He made connections with other artists in Europe and earned their respect. He was inducted into the Royal Society of Arts and worked for a while in Italy and Belgium. In England he studied with the famous muralist, Frank Brangwyn. When he returned to the United States in the 1930s, he took on prestigious mural commissions, such as the Los Angeles Public Library mural, still on view today.

In the 1940s Cornwell returned to illustrating for the Post. He worked out of his studio in Manhattan and lived quite well, often playing with his illustrator buddies at the Society of Illustrators in New York and the Dutch Treat Club, putting on shows and performing for each other.

During his waning years, Cornwell moved into his studio and lived there full time with a friend, drinking heavily. He passed away at age 68. After he died, Cornwell’s widow visited his studio and destroyed a large number of his original paintings, which were reputed to have featured his mistresses. One of Cornwell’s assistants discovered the broken paintings and salvaged what he could. Today several of those original paintings have been restored or retouched, but still bear the scars of having been broken down the middle or cut. The wounds are a reminder of the adventuresome life of the “Dean of illustration.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

talk about “a woman scorned”!. he was lucky she just did that to the paintings and not him!!!

Thanks for this feature, David. Cornwell’s illustration/painting styles were so varied, one could be easily be convinced they were by different artists. The July and September 1918 illustrations show remarkable contrast. The 3 from 1919, ’22 and ’23 as well.

The 1947 ‘Havana’ illustration (complete) yet another very different look. Working real Post illustrators of the time into the picture was sheer brilliance. I don’t know if this was mentioned in the magazine at the time, but it’s great learning of it now. Looking at the group picture of the 6 men, they appear to look faded until you see that they’re actually caught in the glare of the police car’s headlights.

I’m sorry his widow destroyed such a large number of his original paintings, but am also glad at least some were able to be retouched or restored, even if they still bear the long ago scars of a woman scorned.