The last few decades of the 19th century brought unprecedented changes to New York City. The population exploded, growing from about 800,000 people in 1860 to more than 3 million by 1900, according to U.S. Census Bureau numbers. The Metropolitan Museum moved into its impressive Fifth Avenue location in 1880. The Brooklyn Bridge opened in 1883. Construction was completed on the luxurious Dakota Apartments in 1884. The Statue of Liberty was dedicated in 1886.

But just a few miles from the Gilded Age glory, more than a million people — many of them recent immigrants — were packed into squalid, dank neighborhoods where disease ran rampant and thousands of children died every year from the filthy conditions. As images of New York’s iconic landmarks were being shared across the world, the poor suffered just out of sight.

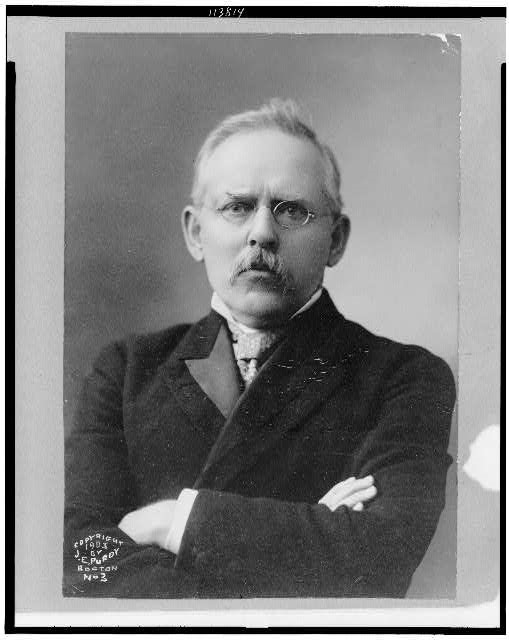

But one man decided to train his camera on the millions packed into the city’s shoddily built, six- to seven-story windowless tenements that offered no plumbing, light, ventilation, or fire escapes. In his efforts to expose New York’s poverty-stricken underbelly, Jacob August Riis produced some of the most iconic photographs of the late 19th century. International Photography Day on August 19 is a good day to remember the mighty impact of his photographs and how they helped the world realize the power of photography to expose injustice and repression.

Arriving in New York City in 1870 from Denmark, the 21-year-old Riis often was forced into the squalid conditions he would later record. By the time he was 28, he had found steady work as a writer, editor, and journalist, and was able to forge a firm path into the middle class. But his job never let him forget the misery he had experienced. A night-shift police reporter for a popular newspaper, he trailed policemen into some of the worst slums and seediest spots in the city.

When Riis tried to expose the squalid living conditions through his writing, he discovered that words had a limited effect. In his 1901 autobiography, The Making of an American, Riis wrote, “It was upon my midnight trips with the sanitary police that the wish kept cropping up in me that there were some way of putting before the people what I saw there.”

In 1887, Riis saw an advertisement heralding the invention of magnesium flash that would allow photographers to illuminate dark places. He found two amateur photographers who were interested in the new technology to help him photograph life in the tenements, but they soon lost interest, so he learned to use the camera himself. He took his first picture at the Potter’s Field on Hart’s Island, where the poorest of the poor were buried. The overexposed photograph was an inauspicious technical beginning, but the image of gravediggers standing over a trench filled with a row of caskets remains as shocking today as it was then.

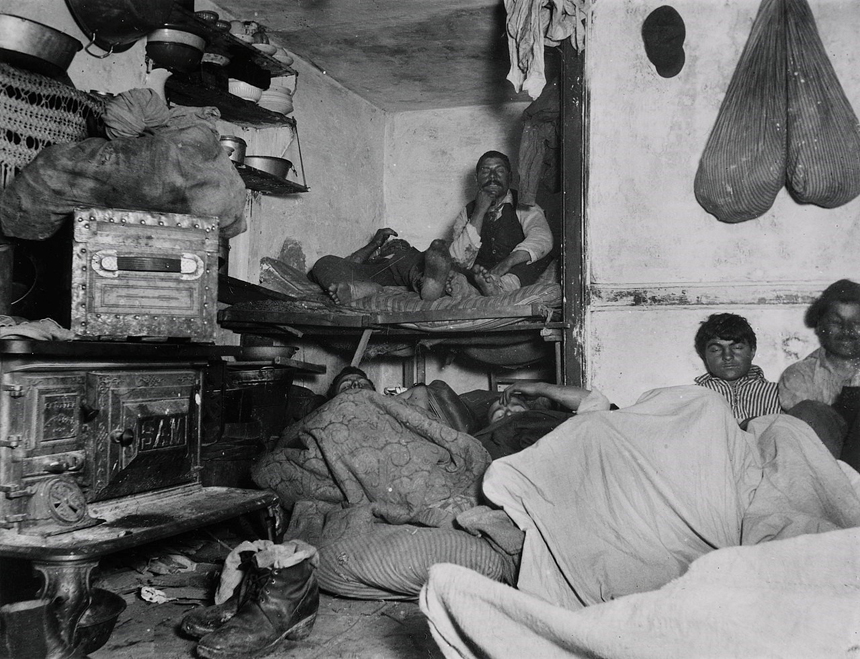

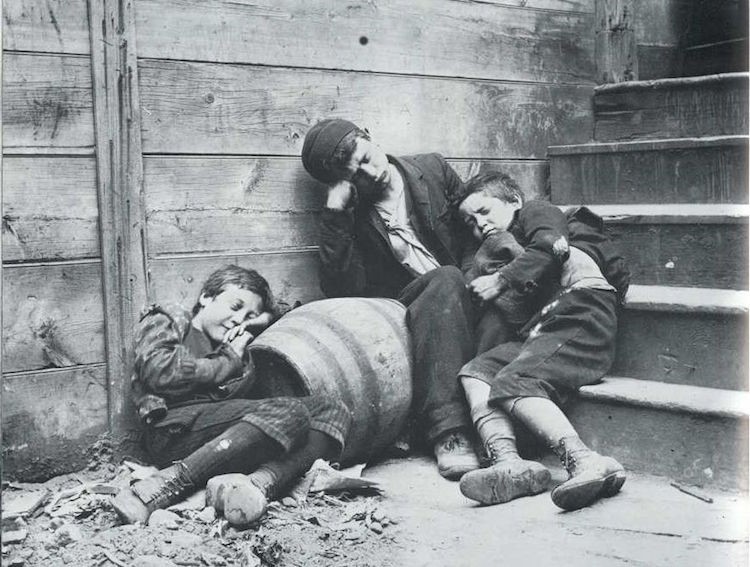

Thus began Riis’s journey of providing photographs that opened people’s eyes to the suffering of the poor. His unique photographs have only gained power and significance in the decades, providing an important historical record of life in the shadows of New York’s wealth. Some photos show only tenement buildings, while others record people sleeping in police stations, living in city dumps, hanging out in bars, or standing in alleyways. Many pictures focus on poor children working in sweatshops, selling newspapers, and sleeping in streets.

These images are raw, vulnerable, and realistic, revealing the chaos and trauma of poverty. Claustrophobic cramped rooms. Broken windows. Dark, streaked walls. Rumpled, torn, and ill-fitting clothes. Uncombed, matted hair and dirty faces. Kids in rags with no shoes, sleeping on stairs and in the streets.

Riis first presented his photographs in lectures, “How the Other Half Lives and Dies in New York,” projecting images onto a screen by a “magic lantern.” He delivered his two-hour presentations to churches and civic groups in New York City and throughout the Northeast. Appealing to the tenets of his Christian faith, Riis petitioned for compassion and help for the people trapped in the tentacles of poverty.

In 1890, he packaged his lecture material into a book, How the Other Half Lives, which became a bestseller and led to national fame. Although Riis characterized immigrants in terms that today would be considered racist, his work as a writer, lecturer, and photographer helped Americans recognize and combat some of the worst poverty and misery in New York. His efforts led to the abolition of the most decrepit tenements and the construction of many city parks, including today’s Columbus Park in what had been Mulberry Bend, one of the City’s most crime- and disease-ridden neighborhoods. Today, Riis’s legacy is commemorated through developments that still bear his name, such as the Jacob Riis Houses on the Lower East Side, the Jacob A. Riis Settlement House in Long Island City, and Jacob Riis Park in Far Rockaway.

By the time he died in 1914, Riis had written 12 books and crisscrossed the country many times to give lectures. “Riis was the first muckraker and the first American social documentary photographer,” Bonnie Yochelson and Daniel Czitrom write in their 2014 book, Rediscovering Jacob Riis: Exposure Journalism and Photography in Turn-of-the-Century New York. “A century later, [his photographs] remain a powerful and unique record of the lived material conditions in turn-of-the-century New York.”

Riis’s work reminds us that much of what he witnessed over 100 years ago remains relevant to this day: that grinding poverty is still with us, and a segment of our society still dwells in homes that are dangerous and unfit, or live unhoused on the streets. But Riis understood we have a hard time fixing problems that we can’t — or don’t want — to see, and he showed how shining a light in dark places can often be the first step toward real change.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thank you so much for such an interesting story about Jacob Riis.

As Christina Stanton writes: “Today, Riis’s legacy is commemorated through developments that still bear his name, such as the Jacob Riis Houses on the Lower East Side, the Jacob A. Riis Settlement House in Long Island City, and Jacob Riis Park in Far Rockaway..”

Riis was A Hero and still is A Hero. Giving his name to developments is not enough. He deserves a much better recognition in New York city and beyond. His name should be given to Streets, Parks, and obviously to have a MUSEUM in his name. JACOB RIIS Museum.

A Museum that tells the history of People of NYC.

Bob McGowan, Jr sounds the same notes I’d have sounded if he hadn’t beat me to it. How does the alabaster cities’ gleaming jibe with these photos, and much more inexcusably, with the fact that 150 years later, millions of our people live day after day in conditions of similar squalor?

Really excellent story of a pioneering photographer and the humanitarian crises of the late 19th, early 20th centuries. If he were alive today, he’d likely be neither shocked nor surprised at the situation now; definitely disappointed.

Horrified how our government is actively working against its own citizens, engaged in wars-for-profit around the world the U.S. has absolutely no right or business whatsoever being involved in. Bullying other nations, looking for trouble to justify starting fights under the guise of democracy, when we’ve lost our own here. The fully orchestrated destruction this month of Maui/Lahaina, while yet another 24 billion was sent into the unaccountable black hole of Ukraine just the other day.

Had he been born 50 or so years later, I have no doubt Mr. Riis would have been one of LIFE magazine’s top photographers for many years.