This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

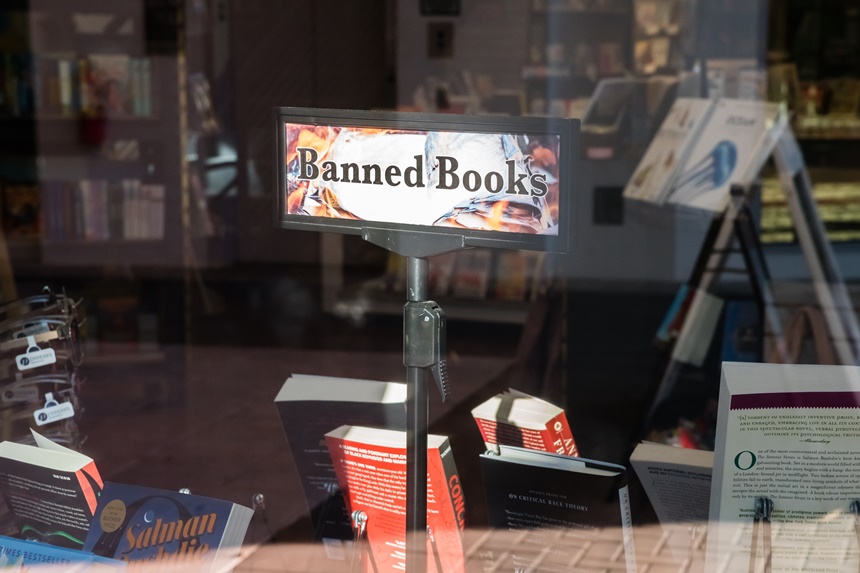

Every October since 1982, America has celebrated Banned Books Week. This week’s version of the annual commemoration is particularly important, as it takes place not only amidst a general climate of book bans, but also just a few weeks after a shocking and violent “metaphorical book burning” in Missouri. At that September 15 “Freedom Fest” event, Republican state senator and gubernatorial candidate Bill Eigel and his supporters took flamethrowers to a pile of cardboard that Eigel claimed represented objectionable books, “vulgar pornographic material” that he argues is “getting in [children’s] hands” through libraries and schools. Eigel pledged that if elected governor he would “burn, bulldoze, or launch [such books] into outer space.”

Book burnings might seem like a practice endemic to totalitarian regimes and fictional dystopian societies, but they have a long presence in American history as well. Indeed, the 1982 origin of Banned Books Week represented a direct response to another book burning, this one perpetrated by an educational institution itself. In 1981, the Bloomfield (New Mexico) school board officially and publicly burned all the school system’s copies of Rudolfo Anaya’s Hispanic American coming-of-age novel Bless Me, Ultima (1972). The board members believed that the novel featured “obscene” Spanish language moments, and, as former school board member turned state senator Christine Donisthorpe put it a year later, “We took the books out and personally saw that they were burned.”

The best response to book burnings and bans is, simply, to read these books and to make sure that students and young readers likewise have a chance to encounter and learn from them. Since we’re in the midst of both National Hispanic Heritage Month and LGBT History Month, here are a handful of books that, like Anaya’s wonderful novel, have been frequently and frustratingly banned and have a great deal to offer young readers and all of us:

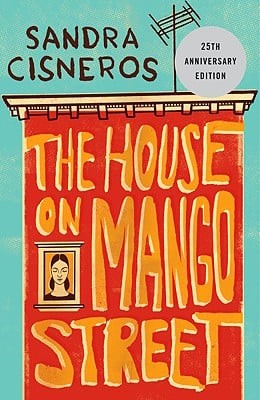

1) The House on Mango Street (1984): Mexican American author Sandra Cisneros’s acclaimed debut short story cycle, which traces the experiences and perspective of its youthful narrator Esperanza across much of her childhood, has been banned multiple times as “unsuitable for age group,” including as part of a 2010 Arizona effort that banned more than 80 books from the state’s public schools. But Cisneros’s stunning book, which uses Esperanza’s developing voice to engage movingly with so many important cultural and social issues, could not be more suitable for young readers.

1) The House on Mango Street (1984): Mexican American author Sandra Cisneros’s acclaimed debut short story cycle, which traces the experiences and perspective of its youthful narrator Esperanza across much of her childhood, has been banned multiple times as “unsuitable for age group,” including as part of a 2010 Arizona effort that banned more than 80 books from the state’s public schools. But Cisneros’s stunning book, which uses Esperanza’s developing voice to engage movingly with so many important cultural and social issues, could not be more suitable for young readers.

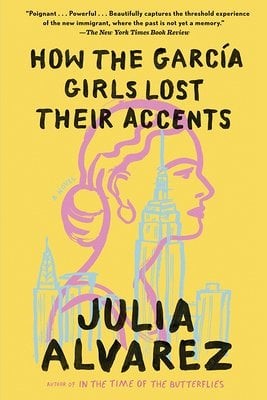

2) How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents (1991): Another debut novel, this time by Dominican American author Julia Alvarez, Garcia Girls uses multiple perspectives and reverse chronology to tell the story of its titular four sisters and their multi-generational Dominican and immigrant American family. It has been banned from high school curricula and libraries many times, as illustrated by the 2008 case in which one parent’s objections to the novel’s “sexual content” led to its entire removal from a North Carolina high school. But the girls’ adolescent experiences with sexuality, which are no different from that found in Romeo and Juliet and countless other high school reading list essentials, are simply one of many ways in which Alvarez creates relatable characters who can connect to many issues for teenage readers.

2) How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents (1991): Another debut novel, this time by Dominican American author Julia Alvarez, Garcia Girls uses multiple perspectives and reverse chronology to tell the story of its titular four sisters and their multi-generational Dominican and immigrant American family. It has been banned from high school curricula and libraries many times, as illustrated by the 2008 case in which one parent’s objections to the novel’s “sexual content” led to its entire removal from a North Carolina high school. But the girls’ adolescent experiences with sexuality, which are no different from that found in Romeo and Juliet and countless other high school reading list essentials, are simply one of many ways in which Alvarez creates relatable characters who can connect to many issues for teenage readers.

3) Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe (2012): Mexican American minister, poet, and novelist Benjamin Alire Sáenz had been publishing books for more than a decade when he came out as gay in 2008 at the age of 54; he used some of those personal experiences as inspiration for his 2012 young adult novel Aristotle and Dante. The novel has been featured on banned book lists almost every year since, including recently on Texas State Representative Matt Krause’s list of 850 works that he believes should be made unavailable at every school in the state. But Aristotle and Dante are two of the most compelling teenage characters in 21st century American literature, and their individual and mutual development across the novel (and its recent sequel) can help many young readers see themselves in an assigned text.

3) Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe (2012): Mexican American minister, poet, and novelist Benjamin Alire Sáenz had been publishing books for more than a decade when he came out as gay in 2008 at the age of 54; he used some of those personal experiences as inspiration for his 2012 young adult novel Aristotle and Dante. The novel has been featured on banned book lists almost every year since, including recently on Texas State Representative Matt Krause’s list of 850 works that he believes should be made unavailable at every school in the state. But Aristotle and Dante are two of the most compelling teenage characters in 21st century American literature, and their individual and mutual development across the novel (and its recent sequel) can help many young readers see themselves in an assigned text.

4) Out of Darkness (2015): Texas English teacher turned novelist Ashley Hope Pérez’s historical novel about an interracial couple pursuing their fraught and fragile romance against the backdrop of the 1937 New London School explosion was the fourth-most banned book in the U.S. in 2021, and has continued to receive numerous parental challenges, ostensibly for its themes of abuse and sexuality. But those complex themes themselves, as well as the depiction of an interracial relationship in a place and time when such romances were literally illegal, are precisely what makes Darkness both so powerful and a compelling window into multilayered historical and cultural issues that can lead young readers to further research topics.

4) Out of Darkness (2015): Texas English teacher turned novelist Ashley Hope Pérez’s historical novel about an interracial couple pursuing their fraught and fragile romance against the backdrop of the 1937 New London School explosion was the fourth-most banned book in the U.S. in 2021, and has continued to receive numerous parental challenges, ostensibly for its themes of abuse and sexuality. But those complex themes themselves, as well as the depiction of an interracial relationship in a place and time when such romances were literally illegal, are precisely what makes Darkness both so powerful and a compelling window into multilayered historical and cultural issues that can lead young readers to further research topics.

5) Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968): Brazilian educator and philosopher Paulo Freire’s groundbreaking exploration of critical pedagogy is a very different kind of book from all the others in this list. But I can’t resist ending this post by noting a truly striking irony: that Freire’s book, which helped create and popularize the concept of democratic pedagogy, of giving voice and power to previously silent and powerless students and communities, has been the subject of numerous challenges and bans. Some of those bans have taken place in totalitarian nations where Freire’s ideas present an obviously dangerous challenge to the powers that be. But in 2012, the Tucson (Arizona) Unified School District banned Freire’s book as part of the state’s overall attempt to ban the discipline of ethnic studies. The increasing presence of book bans in our own society is similarly inseparable from the broader attacks on ethnic studies, Black studies, LGBT histories, and many other curricula and subjects.

5) Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968): Brazilian educator and philosopher Paulo Freire’s groundbreaking exploration of critical pedagogy is a very different kind of book from all the others in this list. But I can’t resist ending this post by noting a truly striking irony: that Freire’s book, which helped create and popularize the concept of democratic pedagogy, of giving voice and power to previously silent and powerless students and communities, has been the subject of numerous challenges and bans. Some of those bans have taken place in totalitarian nations where Freire’s ideas present an obviously dangerous challenge to the powers that be. But in 2012, the Tucson (Arizona) Unified School District banned Freire’s book as part of the state’s overall attempt to ban the discipline of ethnic studies. The increasing presence of book bans in our own society is similarly inseparable from the broader attacks on ethnic studies, Black studies, LGBT histories, and many other curricula and subjects.

During this Banned Books Week, this National Hispanic Heritage Month and LGBT History Month, and this moment overall, there’s no better way to celebrate our freedom than by reading and sharing these banned books.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now