Do ghosts exist? That question has tantalized people for thousands of years, but never more publicly than in 1848. That year, two girls claimed they talked with the dead and sparked American spiritualism, a movement that claimed more than a million followers at its peak.

It began as a prank after Maggie and Kate Fox and their parents moved to a rented cottage in Hydesville, New York. Bored with their rustic surroundings, fifteen-year-old Maggie and her sister decided to frighten their superstitious mother by claiming they talked with a ghost. To prove it, the girls made knocking sounds with their feet and allegedly received return raps from the spirit: once for “yes” and twice for “no.”

The ghost, the girls reported, had been a peddler who had been murdered in the cottage. The next day the frightened Mrs. Fox told her neighbors about it. Before long they began attending the girls’ nightly seances with the ghost. Some of the more skeptical neighbors dug a hole in the basement and were stunned to find a skeleton buried there next to a peddler’s pack. As news of the girls’ clairvoyance spread, their shrewd older sister Leah arrived from nearby Rochester. Sensing an opportunity to make money, she promptly began touring them around New York State.

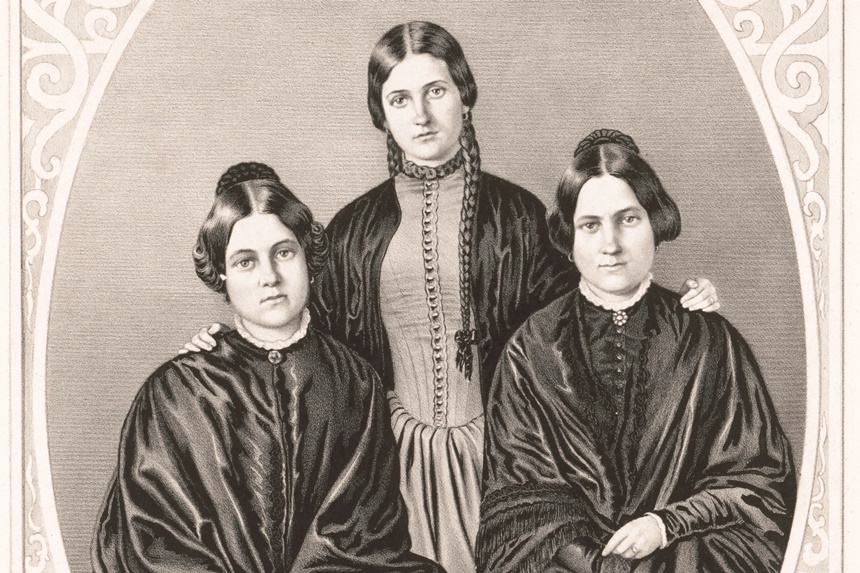

Known as the Fox Sisters, the trio soon attracted the attention of the press. Among them was Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, who wrote about them in his influential newspaper. In June 1850, Maggie and her sisters visited New York City, where they were treated as celebrities and memorialized in a Broadway song. During that visit, the sisters held seances for prominent writers and thinkers like historian George Bancroft, poet William Cullen Bryant, and author James Fenimore Cooper. Simultaneously, hundreds of child and young woman mediums sprang up around the country and created a national craze for seances. Among their followers were prominent judges, lawyers, and intellectuals – including members of Congress.

In October 1852, twenty-year-old Maggie conducted séances in Philadelphia. There she met the physician and famous Arctic explorer, Elisha Kent Kane, who fell in love with her. Smitten, the dashing explorer proposed marriage under one condition: she must give up what he considered the “hoax” of mediumship. For Maggie it was a wrenching decision, for it meant abandoning her sisters and casting public doubt upon their abilities. Ultimately, she acquiesced, gave up conducting seances, and agreed to be educated in order to become a proper “lady” fit to marry the elite Dr. Kane.

A year later, Maggie attended a private academy in Philadelphia while Elisha returned to the Arctic with 17 men on the 144-ton brigantine, the U.S.S. Advance. Their goal was to discover the fate of the British explorer, Sir John Franklin, and his 129-member crew, which disappeared in 1845 during a search for the Northwest Passage. After surviving a dangerous 18 months in the Arctic, Elisha and his crew returned to New York harbor for a hero’s welcome. There, he discovered that his family, which had learned of his secret engagement, threatened to disown him if he wed Maggie, whom they considered a fraud.

Several stormy months passed between the lovers, but finally in late September 1856, as Elisha prepared to sail to England to be honored for his contributions, he again proposed. According to Maggie’s subsequent account in The Love-Life of Dr. Kane, they married in a “Quaker” ceremony, which only her family and friends witnessed. On the eve of his departure, Elisha promised to write her from England through a secret friend.

But soon after arriving in London, Elisha, who suffered from a rheumatic heart, became seriously ill. At his doctor’s advice, he was sent back across the Atlantic to recover in Cuba, where he died in February of 1857. Maggie, meanwhile, who never received Elisha’s letters, learned of his death in from the newspapers. Stunned and impoverished, she appealed in vain to Elisha’s family for her widow’s share of his estate; nor did her lawsuit against them win in the Philadelphia court. One of Kane’s brothers sent her a modest sum, but that soon ran out. Finally in 1866, Maggie persuaded author Elizabeth Ellet to tell her story in The Love-Life of Dr. Kane

In desperation, Maggie returned to mediumship, but like her sister Kate, began indulging in drink. Meanwhile public enthusiasm for the spiritual movement was declining. By then, front page newspaper stories often revealed the deceptive techniques used by mediums. Among the elaborate trappings of the seances commonly conducted across the nation were instances of table tipping, spirit music, suddenly perfumed air, displays of spirit photos, and spirit closets. Finally in 1888, a discouraged Maggie decided that she would plan to make a public confession about spiritualism. Through an arrangement with a promoter, those who attended the confession would pay a costly admission price, the profits of which would go to Maggie.

On October 21, New Yorkers consequently woke to a front-page story in the New York World headlined “Spiritualism Exposed. The Fox Sisters Sound the Death-Knell of the Mediums.” The article went on to explain, “The severest blow that Spiritualism has ever received is delivered to-day through the solemn declaration of the greatest medium of the world that it is all a fraud, a deception and a lie. This statement is made by Mrs. Margaret Fox Kane.”

That night, Maggie appeared at the 3,000 seat New York Academy of Music to make her confession.

From the start, the girls had claimed the rapping sounds heard at their seances were not through any conscious movement of their feet. That had long been their defense, even though earlier physicians had discovered the sounds came from the girls’ trick of dislocating and relocating their knee joints. Consequently, that night at the New York Academy of Music, three doctors held Maggie’s big toe to see if she moved her leg. If she did, it would prove the raps were a trick. The New York Herald reported that “there stood a black-robed, sharp faced widow working her big toe declaring that it was in this way she created the excitement that has driven so many persons to suicide or insanity.” As the doctors held her big toe, “loud distinct rappings” sounded through the hall. “Mrs. Kane became excited. She clapped her hands, danced about and cried ‘It’s a fraud. Spiritualism is a fraud from beginning to end! It’s all a trick! There’s no truth in it!’” By doing so, the Herald declared, Maggie had destroyed spiritualism for all time.

Paradoxically, Maggie recanted her confession a year later in hopes of commanding new sums of money. But her success was limited, and her “recantation” did little more than heap additional discredit upon the spiritualist movement and the mediums who still conducted seances. Nevertheless, Maggie returned to serving as a medium until her death in 1893.

Meanwhile the spiritualist movement attracted the attention of early psychologists. Among them was the distinguished Harvard researcher William James, who investigated clairvoyance and its links to mental illness. Other psychologists like William McDougall and Dr. Joseph Banks Rhine researched extra-sensory perception, or ESP. Parapsychology, the term Rhine used to describe his work, was accepted as subcategory of mainstream psychology at the time.

Maggie’s legacy has continued to the present day. Channeling, spiritual advisors, astrology, crystals, and other mystical objects have become part of popular American culture.

Do ghosts exist? One theme continues to resonate through that question: the hope, if not the belief, that the human spirit endures beyond the grave.

Nancy Rubin Stuart is the author of The Reluctant Spiritualist: The Life of Maggie Fox and other biographies about women.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

You have to be careful with this because what you communicate with and conjure up might be something you don’t want around or know how to contain. It’s dangerous.