Thousands of fair goers lined the streets of Chicago to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the New World. As many as 1.2 million visitors from across the nation came to view the great parade marking the dedication of the World’s Columbian Exposition. The fair itself would not open for another six months, but the Dedication Day Parade was held on October 21, 1892, to coincide with the anniversary of Columbus’s landing.

The World’s Columbian Exposition was not the first “Columbus Day” celebration — this honor goes to the festivities held by the Society of St. Tammany, or Columbian Order, on October 12, 1792, in New York — but it is perhaps the most significant.

Following the resounding success of previous World’s Fairs in London and Paris, America sought to showcase its own national identity on the global stage — and what better way to celebrate American Exceptionalism than with the anniversary of the near-mythic explorer’s arrival in the New World?

Columbus emerged as a national symbol shortly after the American Revolution. Indeed, after violently separating from their mother country, Americans struggled to forge a national identity, and so they increasingly turned to Columbus as a national hero.

As writer and journalist John Noble Wilford notes in his 1991 New York Times article “Discovering Columbus,” it is easy to see the analogy between the legendary seafarer and the newly minted nation. Not only did Columbus endeavor to leave behind the Old World, but he also embarked on a journey to explore the wild unknown, just as Americans faced the dangerous allure of their own western frontier.

While it is commonly accepted that Christopher Columbus was not the first European to travel to the New World — this distinction is usually given to the Viking explorer Leif Eriksson — nor did he ever set foot in the present-day United States, the explorer was a convenient figurehead for the new nation. According to historian Michael D. Hattem, “Columbus’s lack of connections to England made him a much more useful discoverer of America for those trying to express historical independence from Britain.”

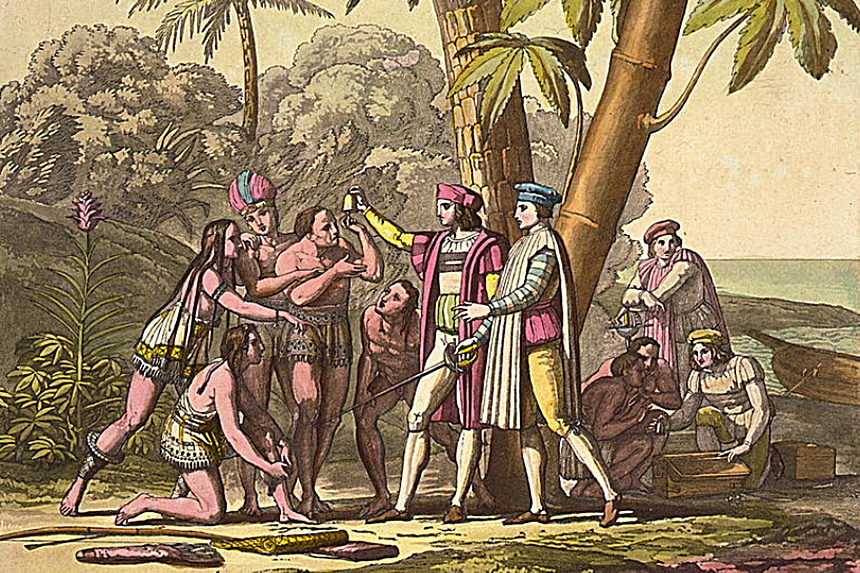

Columbus’s grip on the public imagination grew exponentially following the publication in 1828 of A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, famed author Washington Irving’s account of the explorer’s life. Irving’s Columbus was “a man of great and inventive genius” whose “ambition was lofty and noble, inspiring him with high thoughts, and an anxiety to distinguish himself by great achievements.” His “conduct was characterized by the grandeur of his views and the magnanimity of his spirit,” and “instead of ravaging the newly found countries … he sought to colonize and cultivate them, to civilize the natives.”

Irving’s account of Columbus’s journey has since been proven to be heavily fictionalized. Instead of the bloody genocide and enslavement that the explorer and his troops enacted upon America’s native inhabitants, he is depicted as a paragon of civilization sent by divine order to save the native people from themselves. Nevertheless, Irving’s portrayal of the man as a heroic pioneer resonated with the early American belief in progress as the advancement of (Western) civilization.

As the American population continued to grow and evolve, the mythos of Columbus’s “discovery” became a unifying force for the young nation. Indeed, over 10 million immigrants arrived in the United States between 1820 and 1880, predominantly coming from Northern and Western Europe.

Italian immigrants in particular made up a large portion of these numbers. Starting in the 1880s, there was a wave of immigration from Italy, with as many as 300,000 making the arduous journey. By 1920, more than 4 million Italians had come to the United States, representing over 10 percent of the nation’s foreign-born population.

Yet the Italian-American population faced much religious and ethnic discrimination. According to historian Matthew Frye Jacobson’s Whiteness of a Different Color, the massive surge of immigrants gave rise to a national panic that led Americans to adopt a more restrictive identity. Darker-skinned southern Italians in particular were perceived as uncivilized and racially inferior.

In the face of such prejudice, many Italian-American and Catholic communities turned to Columbus as a representation of their heritage. After all, Columbus was an Italian explorer who sailed for Spain, representing a fusion of cultures and nationalities found within America.

Columbus Day celebrations emerged throughout the 19th century, especially in cities with large Italian populations, like New York City. The first distinctly Italian-American celebration was held there in 1866 with a sharpshooting contest accompanied by a banquet and dance. By 1869, Italian New Yorkers had taken up an annual tradition of decorating ships in the harbor with Italian and American flags and holding a carnival and parade. That year also saw the first Discovery Day Parade in San Francisco, a tradition which continues to this day, though it is now called the Italian Heritage Parade.

Nevertheless, Italian-American immigrants continued to face persecution, and sometimes outright violence. In fact, one of America’s largest mass lynchings occurred in New Orleans in 1891, targeting Italian immigrants. In the aftermath of this crisis, President Benjamin Harrison saw the approaching 400th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the New World as the perfect opportunity to unite the nation.

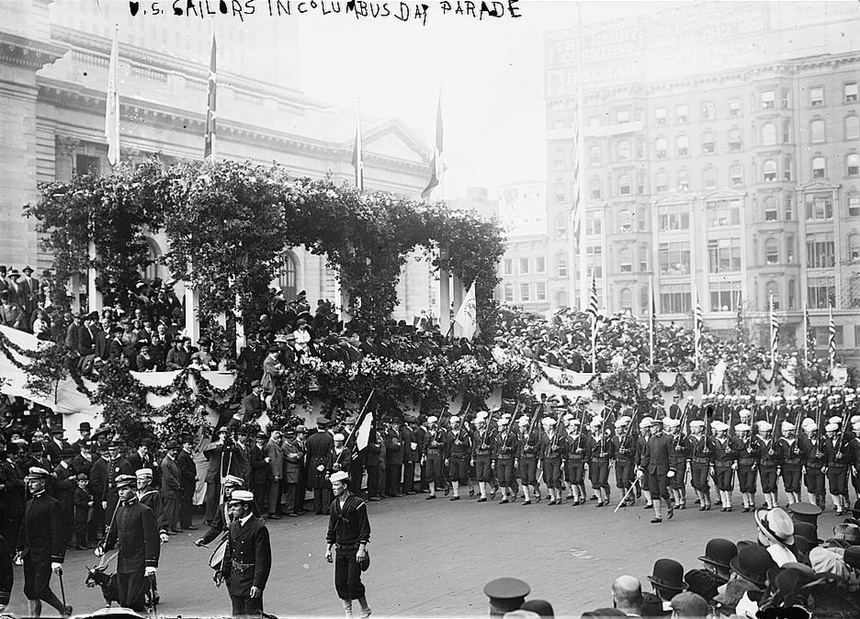

And so President Harrison issued a proclamation in 1892 calling for the first national observance of Columbus Day. Celebrations were held across the country, with the biggest taking place in New York City on October 12, 1892, to commemorate Columbus’s landfall. According to a New York Times article, it was “the greatest crowd New York ever held,” with more than one million people coming out to view a parade of 40,000 military men in uniform, complete with an army of 1,000 Native Americans in “Indian costume with red blankets, painted faces and feathered head gear.”

Of course, New York City’s parade paled in comparison to the spectacle of Chicago’s World Columbian Exposition. Initially commissioned in 1888 with the passage of “A Bill to Provide for a Permanent Exposition of the Three Americas at the National Capital in Honor of the Four Hundredth Anniversary of the Discovery of America” (pdf) by Congress, a bidding war quickly ensued among the nation’s major cities. It was not until 1890 that Chicago was announced as the site of the fair, backed by successful banker and financier Lyman Gage.

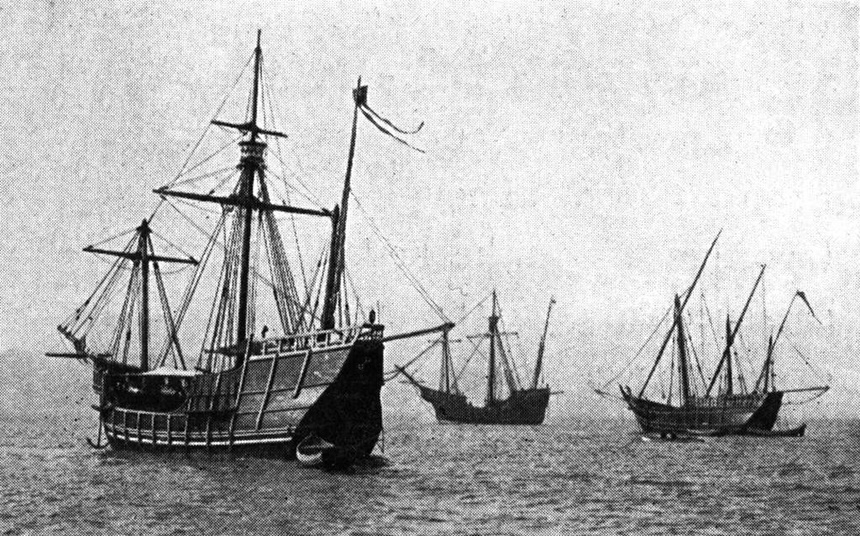

The fair itself covered over 630 acres of the city, centered around the lakefront Jackson Park, likely to represent Columbus’s sea voyage. Chicago architect and urban designer Daniel Burnham headed the project alongside the Central Park landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted to construct over 200 buildings for the affair. Yet the shining crown of the fair were the replicas of Columbus’s three ships, the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa María, which had been constructed in Spain and towed across the Atlantic — re-creating, in a way, the explorer’s initial voyage.

While the opening of the World’s Columbian Exposition was delayed by six months, from October 1892 to May 1893, the fair successfully paid homage to the Christopher Columbus, celebrating his voyage and significant contributions to history, both actual and legendary.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now