Highly intelligent people may be very knowledgeable about everything and everyone, but can be blind to their own shortcomings.

For example, take Ellis Parker, a self-educated man who realized he had a natural talent for solving crimes.

According to John Reisinger’s book, Master Detective: The Life and Crimes of Ellis Parker, America’s Real-Life Sherlock Holmes, he once found a murderer among 175 suspects. He solved a killing by murderers who left no evidence behind. He cracked a string of barn burnings by realizing they weren’t the work of arsonists but of horse thieves. By 1932, he’d worked 286 murder cases and obtained convictions in all but 10. He had risen to become the chief detective in Burlington County, New Jersey.

And then he met the case that destroyed him. Or, rather, the case in which he destroyed himself.

On March 1, 1932, the infant son of Charles Lindbergh was kidnapped from his home in nearby East Amwell, New Jersey. The nation was shocked by the crime and, two months later, the discovery of the infant’s body. Lindbergh was still very much a hero to Americans since becoming the first man to fly solo across the Atlantic.

There was nationwide anger at the culprit and a frenzied search for leads, none of which proved productive. The newspapers provided daily coverage, reporting every fact, and many fictions, of the investigation.

Time passed without any progress, and now the state police and FBI were asking for assistance from all available law enforcement personnel.

Ellis Parker knew he could solve this case as he had so many others. But they hadn’t requested his help personally, perhaps because he’d been critical of the state police in the past. Yet, he’d been called “the American Sherlock Holmes” and “the best detective in America,” and this was the case of a lifetime. He didn’t want to share what would be worldwide credit for breaking the case with anyone else.

Eventually Parker got the invitation he wanted. Harold Hoffman, head of the Department of Motor Vehicles, gave him authority to lead his department’s investigation of the crime (Hoffman made broad use of his department’s “motorized investigative force”). As Parker began digging into the case, he read about a New York psychiatrist who had studied the evidence and developed one of the earliest criminal profiles.

The kidnapper, he said, would be of a low social status but would feel superior to people in authority who he felt held him back from success. He’d work alone, take great risks, and commit a crime to prove his superiority. He’d be near 40 years old, German, and have a criminal record. If arrested, he’d never confess. And he’d always carry one of the ransom dollars as a reminder of his triumph.

Two years into the investigation, a driver at a gas station passed some of the ransom money. Police were able to trace the car to a German who had come to America with a criminal past. In his garage, they found a can with the ransom money hidden in it. The man’s name was Bruno Hauptmann, and he went on trial in January of 1935. He was convicted the following month and awaited his execution.

But Ellis Parker didn’t believe any of it. He knew Hauptmann was innocent because he had the real culprit in his sights. His name was Paul Wendel, a German American attorney and an informant with a criminal record.

Parker had known Wendel for some time. In fact, soon after the kidnapping, Wendel had come to Parker to offer his help in finding the child. From some of his past activities, Wendel had become acquainted with underworld characters, who he thought would know about the kidnapping. Wendel was so convinced, he could find the child.

Parker’s friend from the Department of Motor Vehicles, Harold Hoffman, was now New Jersey’s governor. Like Parker, Hoffman realized he could boost his image if he brought the real kidnapper to justice and exonerated Hauptmann.

He encouraged Parker to unofficially work up a case against Wendel as the date for Hauptmann’s execution drew near. Parker tried to lure Wendel to New Jersey for questioning, but couldn’t get him to leave New York.

Parker was growing desperate to save Hauptmann and gain renown as the detective who found the real kidnapper. He was skeptical of the evidence in Hauptmann’s trial, believing he was the only one who could see the truth. But time was running out; only two days remained before Hauptmann’s scheduled execution. In previous cases, Parker had bent the law to solve a crime. For this case, he was ready to go even farther.

He sent his son and three associates to find Wendel at his New York hotel and abduct him at gunpoint. The men hustled Wendel into a car and took him, blindfolded, to a house in Brooklyn, where he was chained to a chair in the basement.

His abductors told him he’d make a lot of money if he confessed to the kidnapping. When Wendel refused, they began beating and kicking him, burning his skin with a hot light bulb, and hanging him by his arms, Reisinger writes in Master Detective. After a week of beatings, the men threatened to bring in Wendel’s family and kill them in front of him. Wendel finally agreed to write a confession.

Now his abductors were reassuring, telling him he’d be taken care of, he’d make a lot of money, and he was doing the right thing. After completing the confession, Wendel was blindfolded, driven around for a while, then delivered to Parker’s house. Parker confined Wendel to a state mental hospital and directed him to write a more detailed confession.

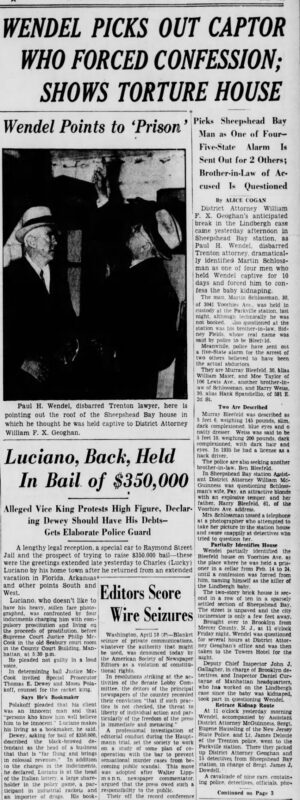

With this in hand, Parker hinted to the media that he had found the real kidnapper as he handed Wendel over to the authorities.

The first thing Wendel did was admit that the confession coerced; he was abducted and tortured to confess.

Parker was unshaken. He had expected Wendel to deny the confession. So Parker was shocked when he, his son, and all his associates were all arrested for kidnapping.

On April 27, 1937, Parker’s trial began. He tried to use the trial to lay out his case against Paul Wendel. He introduced several theories of how evidence had been planted on Hauptmann, and that the kidnapper profile that matched Hauptmann also matched Wendel. He even tried to introduce the idea that the infant’s remains recovered in the woods near the Lindbergh house weren’t those of young Lindbergh.

None of it helped. Parker, his son, and his associates were all found guilty for the abduction. The judge sympathized with Parker, believing that he’d acted on the public’s behalf, but he had come to disregard the law he had been empowered to enforce. He sentenced Parker to six years in prison. He son received a three-year sentence. The men who committed the abduction were sentenced to 20-year terms.

Interviewed when he arrived at Lewisburg, Parker said he held no bitterness in his heart against anyone. He talked of picking up his life when he left prison and never looking back at this interval, according to Reisinger’s book. But he never got that chance. He died in 1940 at the Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary, one week before receiving a presidential pardon.

To the end, he couldn’t accept the fact that he’d been wrong.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This really is a crazy story, Jeff. How Ellis Parker allowed himself to get caught up in something this outrageous to commit such a crime to lay claim HE solved the kidnapping, seems hard to believe. But no. It was because the victim was the Lindbergh toddler. The name and the fame. That’s it right there. He outsmarted himself. The ‘big name’ crime-ridden 30’s; I’ll say.