New York hadn’t seen so much gunfire and death since the Revolutionary War.

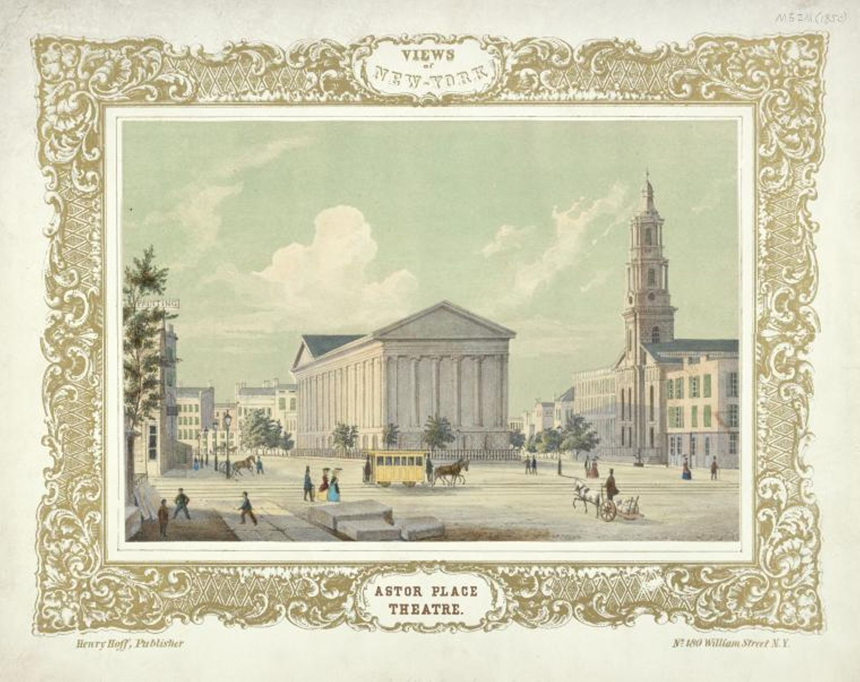

On May 10, 1849, a riot of over 10,000 angry people broke out at Astor Place in central Manhattan. When it was over, a stately theater had been attacked, its windows smashed and doors broken in, and up to 32 people lay dead in the street.

There were many at the time who would have told you the melee was caused by the rivalry of two actors: William Macready and Edwin Forrest. But the riot was about much more than that. It was about the way America was growing and the division that was developing among its people.

At that time, a minority of wealthy New Yorkers were living a life of privilege in the elegant homes of Upper Manhattan. These were the merchants and financiers who, like John Jacob Astor, for whom a plaza and theater were named, had grown rich in America. They generally copied European fashion and were strongly influenced by British tastes. For this reason, they admired William Macready, the famed English dramatist and interpreter of Shakespeare who was now concluding his third tour of the U.S.

On May 7, he would play the lead in Macbeth at the Astor Theater.

Macready’s style was subdued and refined. He insisted on rehearsing Shakespeare and sticking to the original text, though he would oblige audiences if they demanded an encore of his death scene (earning him the name “Die Again Macready”).

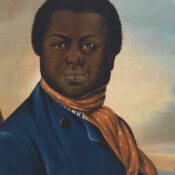

His dramatic opposite was the American actor Edwin Forrest, who was idolized by the people of Lower Manhattan. Most of these New Yorkers were poor, and a large number were immigrants. They crowded into tenements and survived among filth, disease, and crime.

Forrest had begun his career among these people and had come to exemplify an “American” approach to Shakespearean acting. Compared to Macready, Forrest was loud and energetic. He overwhelmed audiences with his passionate, physical performances.

Both actors had performed in each other’s countries. Macready’s last tour of Britain had been unsuccessful, and he’d blamed Forrest for the bad reception his home country had given him.

When Macready came to America, Forrest followed him. Sometimes he would perform the same role in a different theater of the city where Macready was staying. Or he would simply attend Macready’s performance and hiss.

The night that Macready was scheduled to play Hamlet at the Astor, Forrest would be playing the same role in theater not far away.

That evening, the richly attired gentry draw up to the Astor Theater in their private carriages. The display of privilege only added resentment to several working-class ticket holders approaching the theater doors.

Officials were expecting some trouble. Days before, someone had thrown half a dead sheep’s carcass on the stage while Macready was performing. Now, on May 7, the management noted a large number of poorly dressed New Yorkers had begun filing into the Astor Theater. They didn’t look like Macready supporters.

To no one’s surprise, when the actor came onstage, they began booing and hissing. He stopped, waiting for the demonstration to die down, but the noise continued. Now he was pelted with eggs and coins. He walked offstage, and the performance was cancelled. The following day, he announced he was returning to England immediately.

Wealthy New Yorkers begged him to stay for just one last performance on May 10th.

To ensure peace and safety, the city ordered the 7th and 8th regiments of the militia to be stationed nearby and ready to intervene. The windows at the Astor Theater were barricaded and all unused doors boarded up.

Police were posted inside. Audience members were screened as they entered to ensure that no trouble maker sneaked in with the aristocrats.

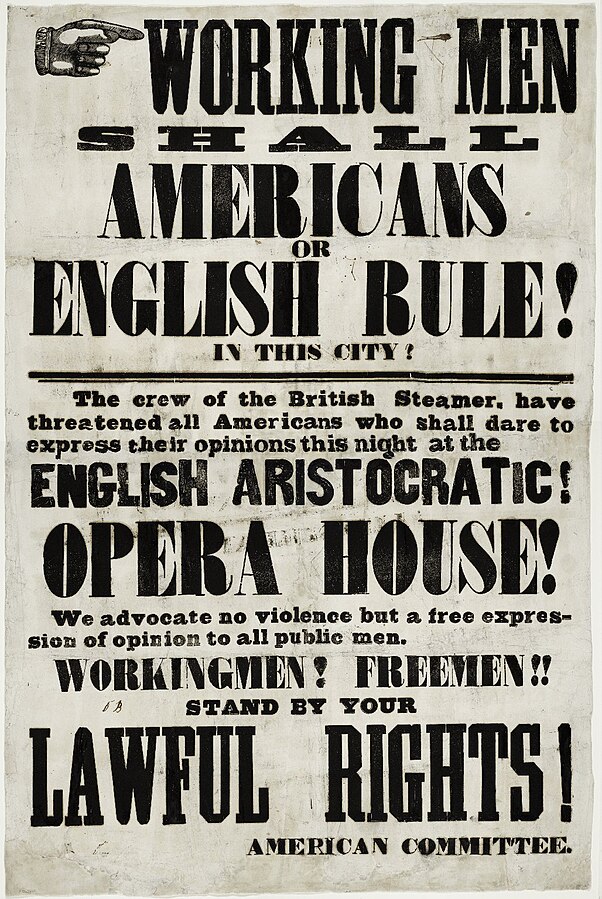

By now, demagogues had stoked the resentment of nativists in lower Manhattan. Forrest had become America’s response to the British cultural invasion, the champion of all the New Yorkers kept out of Astor Place Theater.

A group that was intent on starting a demonstration printed a poster goading the rough crowd in the Bowery and Five Points neighborhoods. It claimed that British sailors were threatening Americans who “dare to express their opinions” about Macready at the “English Aristocratic Opera House,” meaning the Astor Place Theater.

The play began and went along smoothly until the third act, when Macready made his entrance. His supporters cheered and waved their hats and handkerchiefs, while others booed and hissed. After ten minutes of this noise, a sign was placed on the stage reading “The friends of order will keep quiet.” It silenced Macready’s supporters but had no effect on his critics, who drowned out the actors’ voices.

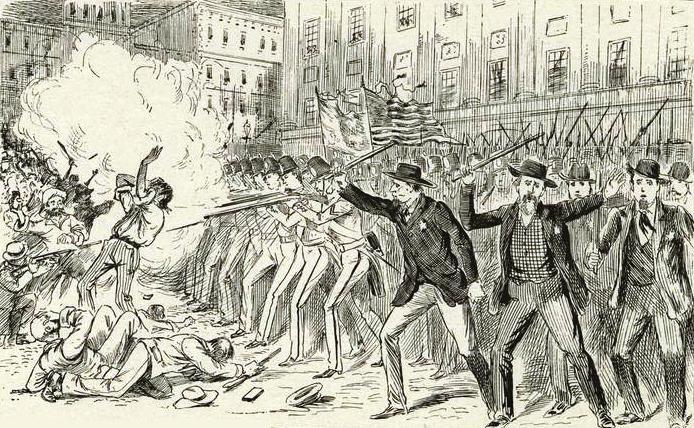

The police entered and dragged out the protesters, one by one. In the quiet that followed, audience members could hear the roar of protestors outside. An estimated 10,000 people had ringed Astor Place. Now stones began striking the covers over the windows. There was the sound of glass breaking and paving stones landing on the floor inside the lobby.

But Macbeth proceeded for another two acts and ended just as a group of 30 protesters had almost succeeded in forcing their way through a shattered door. The audience was able to exit with the help of police and the militia, which had been called up.

Cobblestones began sailing over the crowd, knocking down several soldiers. Rioters tried to wrest muskets away from the militia. Minutes later, shots were fired by the militia in front of the theater. A second volley followed, as did a third and a fourth.

Rioters who hadn’t been hit assumed the militia had been firing blank cartridges. They were surprised to stumble across dead bodies in the street. Most, according to the New York Tribune of May 11, “were innocent of all participation in the riot.” They were carried away to hospitals, hotels, and other destinations, which made it difficult to get a definitive account of the dead. Accounts at the time listed approximately 22 people dead and 120 injured.

Meanwhile, Macready had disguised himself, slipped through the crowd, and was on the train to Boston before the sun came up the next morning. News of his departure dampened much of the ire from the rioters, and Astor Place slowly emptied.

In the following weeks, a number of New Yorkers, including influential residents of Upper Manhattan, felt something had to be done before the city settled into continual violence. The city’s laissez-faire attitude hadn’t helped the poor struggling for survival. Even the fire companies brawled with each other in the street for the rights to put out a fire, which was ignored until one company drove off the other. And competing police forces began a melee directly in front of City Hall. The city’s people needed to be unified and conditions of the poor needed to be addressed.

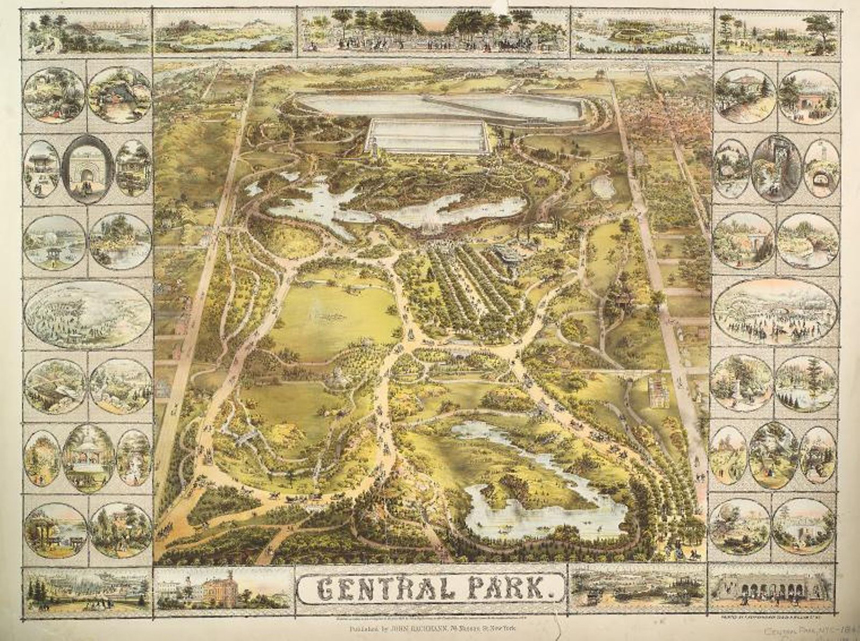

The riot marked a turning point in the fortunes of the city. Over the next ten years, the reformers worked to build better public schools and improve sanitation. People had access to free higher education.

A big part of the effort to make the city more livable was the construction of Central Park, a green space at what was then the edge of the city. Its 843 acres of meadows and forest included fountains, a lookout tower, and a dairy where milk was given to the needy. New Yorkers from almost every level of society came to the park, and a variety of citizens would mingle on its lush, neutral grounds.

New York has experienced over 30 major civil disturbances since the Astor Place riots, including the infamous Draft Riot of 1863, which cost the lives of 119 people. But never again did the impoverished strike out against the affluent by rioting.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Wow Jeff, I’d NEVER heard about THIS before! It really came down to class warfare, haves vs. the have nots that had probably been brewing for a long time and the “Macbeth’ event was the last straw. This was extremely serious. It’s too bad it took the event for things to come into place and being for those of us not in the privileged class. The English vs. American actors here at another time might not have been a problem. This wasn’t that time.

1849, though 73 years after America won it independence, still wasn’t far enough away historically for lingering resentments (and hatred) to have fully subsided. For the wealthy American class to be treating those less fortunate like dirt when they could and should have been helping to uplift them at a relatively small cost collectively, had to have been infuriating. America had won its independence from the British, only to be treated the same way by Americans. 175 years later, we’re still dealing with it, on steroids, from Washington, D.C.

I was glad to read over the next 10 years better sanitation was put into place, with better schools and free education. Beautiful Central Park speaks for itself as a physical manifestation of being a great equalizer of classes and civility. In the 21st century, the way things are going, let’s hope it isn’t destroyed.