They’re not just slacks or skirts, jackets and tops, hats and ties. They’re more than a printed pattern designed to blend into the background. From West Point cadets’ ceremonial swords and hats to functional fatigues, military uniforms convey a sense of belonging; the person wearing them is part of something larger than themselves. As women became part of American service branches during the 20th century, uniforms made them readily recognizable as members of the nation’s defense team. Women’s uniforms through the years have also offered a record of what Americans and military leaders think a servicewoman should be.

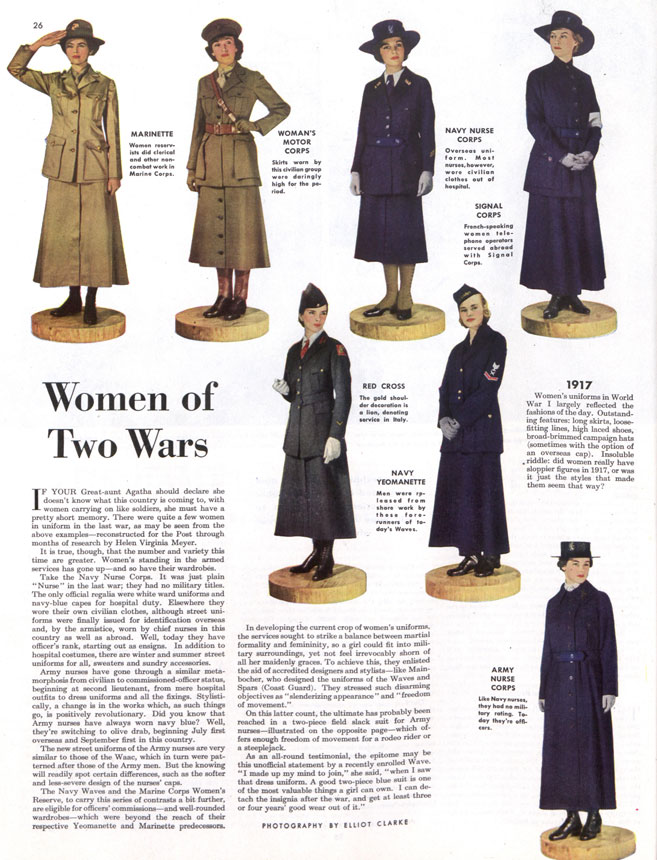

In late May 1943, The Saturday Evening Post published a two-page article about how servicewomen’s uniforms had changed from World War I to World War II, noting “Women’s standing in the armed services has gone up — and so have their wardrobes.” The seven World War I models include nurses from the Navy Nurse Corps and Army Nurse Corps. While they would have worn white nursing uniforms and capes while on duty in hospitals, the article showcases their more formal uniforms used overseas. Most of the World War I uniforms include jackets extending well below the waist and a pair of gloves. The writer asks, “did women really have sloppier figures in 1917, or was it just the styles that made them seem that way?”

Perhaps “sloppier” was not the right word, but compared with the World War II figures on the following page, women’s World War I uniforms do seem a little baggier and less well-fitted. The emphasis on long skirts and jackets makes it clear that no one would confuse a woman in uniform for a man in one. Women in uniform were a much less common sight in World War I, but for those who encountered them, there would be no doubt that they conformed to that era’s ideas of feminine respectability.

In 1943, femininity came to the forefront. World War II uniforms “sought to strike a balance between martial formality and femininity, so a girl could fit into military surroundings, yet not feel irrevocably shorn of all her maidenly graces,” the article says. Eight of the ten World War II uniforms pictured are improvements from the World War I models, with better tailoring, shorter skirts, and even handbags. The Army Nurse Corps and the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS, who were civilians) appear in much different attire, including cargo pants and, for the WAFS, a bulky, fur-lined leather jacket.

More than 350,000 women served in uniform during World War II. One of the challenges military leaders faced was convincing Americans that military service was appropriate for women. Uniforms played an important part in this not-always-successful effort. By the time The Saturday Evening Post ran its feature on women’s uniforms, a nationwide slander campaign had many Americans believing that servicewomen were immoral and promiscuous. Teaching servicewomen how to wear their uniforms and how to behave in public became important strategies for countering these rumors.

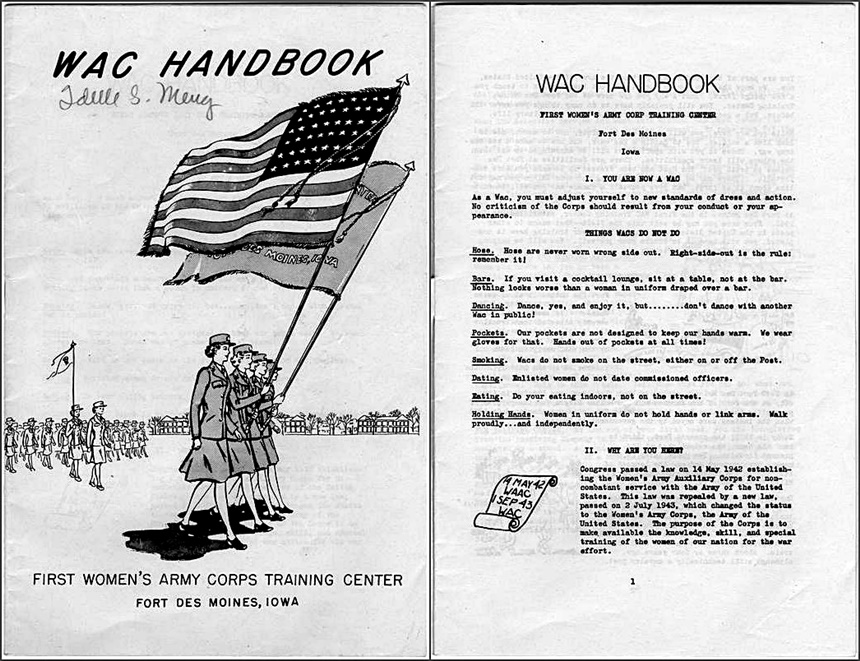

The Women’s Army Corps (WAC) Handbook given to recruits at Fort Des Moines in 1944 provided clear instructions on “Things Wacs Do Not Do.” In addition to a list of specific behaviors, the handbook cautioned new Wacs to wear their hose right-side-out at all times, and to keep their hands out of their pockets. “Our pockets are not designed to keep our hands warm. We wear gloves for that!” The handbook also included more than two full pages dedicated to “This Business of Being Feminine” and “What to Wear.”

The handbook did not give recruits instructions about what type of undergarments to wear but did tell WACs, “The rule is that you maintain a neat, military appearance at all times.” In some instances, the handbook noted, servicewomen might need to wear a girdle, better known today as shapewear. “Incidentally, remember to wash these personal articles, as well as all of your lingerie, often,” the WACs were reminded. During World War II, WACs serving in Europe could not buy some clothing items in civilian stores due to rationing. The Army began stocking bras and girdles on post exchanges so that servicewomen could buy them. A similar problem occurred in the Pacific theater of the war: WACs did not get enough clothing rations to purchase undergarments in Australia, and in both the Philippines and New Guinea, women could not even locate such items to buy. Some women asked family members to send them undergarments from home.

Being feminine did not mean sacrificing function, however. As The Saturday Evening Post article notes, “freedom of movement,” was also a goal in creating women’s World War II uniforms. The feminine standard set in World War II would continue for another three decades. In the early 1950s, military recruiters made parallels between Miss America and American servicewomen. Basic training and boot camp included sessions on personal grooming, including how to wear makeup. In 1967, the Marine Corps hired Pan Am Airways grooming experts to teach “Image Development” courses specifically for Women Marines.

Servicewomen did not always share the same ideas on the best way to achieve a feminine look. In 1968, members of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) in Vietnam argued that they should be able to wear more practical uniforms. Their living and working conditions made it challenging to keep the dressier uniforms neat and clean. (Unlike nurses serving in Vietnam, WACs were not allowed to wear fatigues.) “Being feminine,” one enlisted woman argued, “does not mean wearing a dress.”

By the 1970s, military leaders stopped discussing concerns about servicewomen’s femininity in uniform. In the decades since, camouflage has become more common attire for men and women. Now, skirts and slacks are both options for servicewomen. Today, U.S. military branches emphasize the importance of a “well-groomed and professional appearance.” This has not changed from earlier in the twentieth century, but femininity is no longer a must. Military leaders now address questions of function more than ever.

In 2021, both the Air Force and the Army released new grooming standards, including how women in uniform may wear their hair. In 2022, the Army announced it was working on designs for a For more than a decade, work has been underway to develop body armor specifically for servicewomen, but this remains incomplete. The Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services (DACOWITS) recommended “gender appropriate and properly fitting personal protective equipment and gear for both training and operational use” in 2018, and renewed that call, with requests for an update, in 2022.

Women’s military uniforms have and will continue to change. For decades, military leaders focused on how uniforms fit, thinking primarily about what people would see when they looked at a servicewoman. Today, however, fit and function go hand in hand.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Another great, well researched article, Tanya. A topic most Americans would overlook, if they even thought of it at all. I’m guilty of the latter, and appreciate the enlightenment. Women’s uniforms had to change with the times so they could be more comfortable, and to be able to do a better job. Fit and function should always go hand in hand.

Having said that, no women or men should ever be put in harm’s way or used as human expendable casualties seen as just part of the government’s “cost of doing business” for their greedy, undeclared conflicts for oil and other commodities under the phony pretense of ‘democracy’.