Culture moves in waves, with certain ideas or movements cresting depending on the pull of various societal forces. Real world worries can ripple out to affect music, movies, and more as people grapple with concerns that affect their everyday lives. Forty years ago, America experienced a moment of heightened nuclear anxiety, and those fears found expression in ways that helped people deal with it, but also occasionally left negative impressions of their own.

Paramount newsreel of “The Truman Doctrine” Speech (Uploaded to YouTube by Harry S. Truman Library)

After the end of World War II, the United States soon became embroiled in the Cold War with the Soviet Union. Post-war territorialism and the inherently different political philosophies between the two superpowers led to the initiation of the Truman Doctrine, designed to stop the spread of communism. The ensuing arms race and space race ratcheted up the tension in a world already exhausted by global conflict. The Korean War, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Vietnam War, and proxy conflicts in Latin America and elsewhere made it seem like the situation would only escalate over time. Additionally, U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s enthusiastic advocacy of the Strategic Defense Initiative (also known as the “Star Wars program”) made the Soviets deeply suspicious of what America might do with weapons platforms in orbit.

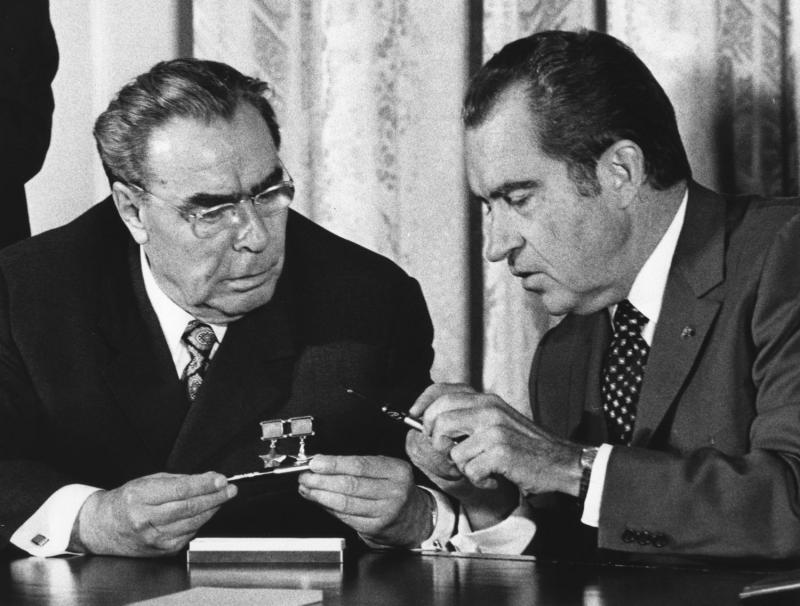

Amid this, Leonid Brezhnev became leader of the Soviet Union in 1964. His legacy would be a complicated one. Even as he pursued the arms race and continued to strong-arm other countries in Europe and western Asia, he advocated a relaxing of the ongoing political tension between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. However, with his death in November of 1982, Brezhnev’s experience gave way to Yuri Andropov’s brief, but chaotic, tenure. While dealing with worsening health, an economy in shambles, a land war in Afghanistan, and staggering increases in military spending, Andropov was at the center of even greater global tension. Unfortunately, he was also dealing with kidney failure, and was hospitalized in August of 1983.

Things took a turn for the worse on September 1, 1983, when the Soviet Union shot down a civilian airliner from South Korea that they claimed had strayed into their airspace. Korean Flight KAL-007 had carried 269 passengers and crew, among them U.S. Congressman Larry McDonald from Georgia. While the act remarkably didn’t lead to further open hostilities, it greatly exacerbated the general anxiety that people felt about the world situation. It was eventually revealed years later than the shoot-down occurred after an errant keystroke identified the plane as a hostile craft rather than a passenger vessel.

With all of that building in the world, it should have been obvious that reverberations would be felt in entertainment — the “zeitgeist,” or “the spirit of the age.” Writer Alan Moore referred to it as “ideaspace,” a sort of dimension where all of humanities and stories and histories exist at the same time, and which creative types tap into for inspiration. This, in Moore’s estimation, led to situations with writers with no knowledge of one another’s work in progress turning in very similar takes on the same idea. The nuclear anxiety of the time started pulling and shaping the art that was being created within it.

“99 Luftballons” by NENA (Uploaded to YouTube by NENA)

Interestingly, a song was released earlier in the year that would eerily prefigure the notion of a radar misinterpretation leading to disaster. German group NENA released “99 Luftballons” in March of 1983. The song would be a worldwide hit over the next two years in both German and English, but the real meaning of the tale of a batch of released balloons triggering a nuclear exchange was lost on many listeners. Similarly, Men at Work’s June 1983 single “It’s a Mistake” addressed the same themes. The cover for the 45 single even showed a caricature of Soviet and U.S. military leaders shaking hands while hiding missile launch controls behind their backs.

Barefoot Gen U.S. trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by RetroBoom)

In Japan during the summer of 1983, an anime adaptation of a popular historical manga played into themes of nuclear angst with its unflinching depiction of the bombing of Hiroshima. Directed by Mori Masaki, Barefoot Gen was based on Hadashi no Gen (Barefoot Gen) by Keiji Nakazawa. Nakazawa was six years old when the bomb fell on his city, leading him to create a body of work, both autobiographical and fictionalized, about his experiences. Gen was his largest, a ten-volume manga that would be adapted repeatedly for other media, including three live action films between 1976 and 1980 and a second anime in 1986. However, it was the original anime that would become best known in America, getting a subtitled version as the form grew in popularity in the States.

The trailer for Testament (1983) (Uploaded to YouTube by Trailer Chan)

Writer Carol Amen had been thinking about what life after a nuclear exchange might be like for many years prior to 1983. In 1969, she wrote a three-page story, The Last Testament, that would eventually see print in the St. Anthony Messenger in 1980 and Ms. Magazine in 1981. PBS Playhouse moved to adapt it for television with a script by John Sacret Young and director Lynne Littman attached. However, Paramount Pictures picked it up for a theatrical release, and Testament reached theaters on November 4, 1983. A quiet and elegiac film, Testament relates the story of a small community struggling to survive outside of San Francisco after a nuclear attack.

Though Testament was a tough watch and not available in some areas, it drew high praise from the likes of Roger Ebert, who gave it four stars. Jane Alexander would be nominated for a Best Actress Oscar for her work, and the Youth in Film Awards nominated Ross Harris and Roxana Zal. PBS would show Testament the following year, leading to more critical praise. Today, it remains highly regarded in the science fiction community for its efforts to realistically depict the aftermath of a nuclear exchange.

But the central cultural event that turned on nuclear fears in America happened when The Day After aired on ABC on November 20. Development for the film had begun in 1981, as the theme of nuclear war was certainly in the air. Director Nicholas Meyer, already well-known for top-notch science fiction films like Time After Time and Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan helmed the project; the screenwriter was Edward Hume, who had a prodigious reputation of his own based on his knack for writing successful pilot scripts for procedural series like Cannon, Barnaby Jones, Toma, and The Streets of San Francisco and for penning the award-winning inaugural HBO original film, The Terry Fox Story. Meyer and Hume dug into the project with utter seriousness, conscious of representing the humanity of the survivors of a nuclear attack while also depicting their suffering in brutally realistic detail.

Trailer for The Day After (Uploaded to YouTube by Cinema Ambiente)

ABC promoted the film heavily before it aired, and some schools even assigned it as viewing for students for discussion. When the TV movie aired, it was viewed by an audience of an estimated 100 million people in the U.S. ABC had taken great pains to prepare viewers for the harrowing experience that the filmmakers had created, going so far as to establish a 1-800 number with counseling and devoting the episode of Nightline that followed to discussion of the film. The movie’s depiction of the attack and the horrific aftermath of radiation sickness landed hard.

Some conservative critics, like Ben Stein and Phyllis Schlafly, took issue with the film, believing it undermined America’s nuclear strategy. However, it had the opposite effect on one very important conservative figure: then-president Ronald Reagan. In his diary, later recounted in the book An American Life, Reagan addressed that the film affected him emotionally and made him reconsider the notion of “mutually-assured destruction” in the arms race. Four years later, Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet premier, put their signatures to the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, which dramatically curtailed the nuclear efforts of both sides. In his memoirs and conversation, Reagan would attribute the beginnings of his efforts to reduce the nuclear arsenal to his viewing of The Day After.

While nuclear anxiety may have been at a high point 40 years ago, it certainly didn’t stop America from fighting the Soviets on the pop culture front. For the next few years, Hollywood waged a proxy war with communism in movies like Rambo: First Blood Part II and John Milius’s invasion thriller, Red Dawn. Russian spies were a fixture of TV shows and battled James Bond in films like The Living Daylights. The topic had more serious moments as well, with Threads, the BBC’s harrowing answer to The Day After in 1984, and Moore and Dave Gibbons’s seminal comics work Watchmen.

However, with the ascension of Gorbachev, his willingness to deal with Reagan, and his policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (economic reform), Soviets and Russians began to recede from being “the bad guys” in pop culture. 1988’s Red Heat featured action superstar Arnold Schwarzenegger as a Soviet cop who comes to America and teams with a Chicago detective (Jim Belushi) to catch a crime boss. DC Comics created a new wave of Russian heroes like the teen team Soyuz, and Marvel renamed the Soviet Super Soldiers as the Winter Guard while slightly softening their role as antagonists. By 1989, Moscow was hosting the Moscow Music for Peace Festival, which invited Western hard rock and metal bands to Russia for the first time; the unlikely ambassadors included Bon Jovi, Mötley Crüe, Cinderella, Skid Row, and the prince of darkness himself, Ozzy Osbourne. A live audience of 100,000 attended, and millions more watched live in 59 countries (including the U.S., via MTV) as metal played out an ’80s take on John Lennon’s “hair peace.”

As with anything, the tides of culture eventually shift, and the daily fear of nuclear exchange began to recede, replaced instead by other worries. Is it that it no longer seems like an imminent threat, or is it that we have so many other things to worry about, that nuclear anxiety just seems like another thing on the list? If there’s a positive element to be drawn from that season of worry 40 years ago, it’s that two men on opposite sides of both the earth and the political spectrum found a way to make the world safer after the expression of art frankly and brutally demonstrated the potential consequences of the alternative.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

1983 was a VERY scary time! Where I lived at the time, the powers that be declared Reagan as a nuclear-war activator, and then there was “The Day After” plus the info-comic “When The Wind Blows” , a fable about an elderly couple facing nuclear aftermath. I lived 1 hr. from an East Coast US Navy base.

BTW, welcome back Saturday Evening Post!!!