This month marks the 75th anniversary of the Cold War.

It semi-officially started in March 1947, less than two years after the Second World War.

The immediate cause of the new war was Russia-backed insurgencies in Greece and Turkey. But the Cold War had been coming on for months as eastern European countries were falling under Soviet influence.

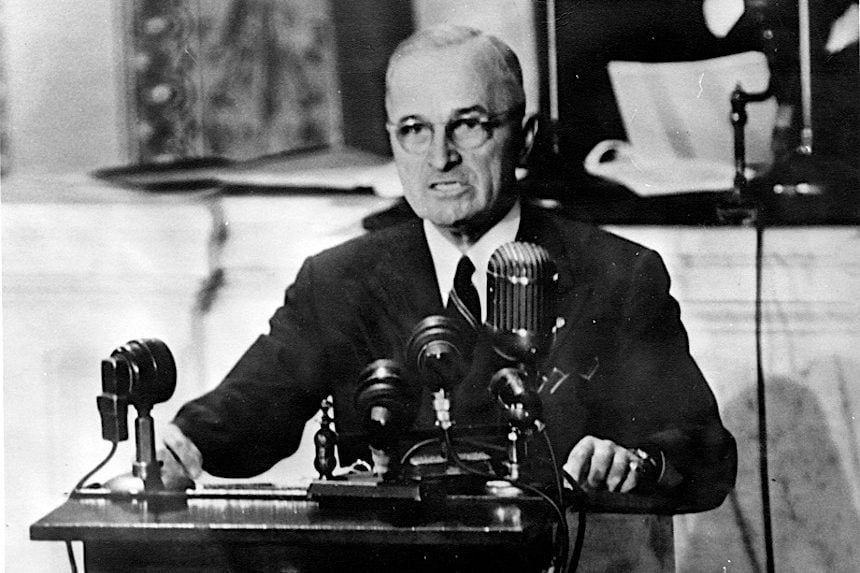

President Truman acknowledged the struggle had already begun when, on March 12, he asked Congress for funding to help nations resist subjugation by armed minorities or outside pressures by agents of communism. He said that America should use financial aid to help struggling nations remain free.

In his speech to Congress, he said:

We shall not realize our objectives, however, unless we are willing to help free peoples to maintain their free institutions and their national integrity against aggressive movements that seek to impose upon them totalitarian regimes. This is no more than a frank recognition that totalitarian regimes imposed on free peoples, by direct or indirect aggression, undermine the foundations of international peace and hence the security of the United States….I would not recommend it except that the alternative is much more serious.

Despite the fact that Truman had an approval rating around 35 percent, and that his party had just lost control of both houses, the predominantly Republican Congress agreed to his request. The U.S. adopted the Truman policy of containing Soviet aggression, and the Cold War began.

A July 5, 1947, Post editorial, “Why the Truman Doctrine Makes Sense,” notes there was great deal of uncertainty about such an open-ended doctrine. “Just where this will lead is a speculation, as every public act must be in a revolutionary period like the present.” But it would confront the USSR with the possibility that continued actions might mean war. This action might delay further Soviet just long enough to allows the European nations shattered by war to rebuild their economies.

The U.S. soon launched an ambitious plan to rebuild our allies, as well as our former enemies. The Marshall Plan, as it was called, established cooperation with European nations to prevent hunger and social collapse, and to halt Soviet expansion.

Unfortunately, financial aid proved insufficient to stop the Soviets. In 1948, America had to use its Air Force to supply food and vital supplies to West Berlin when the Russians cut off all transportation into the city. The U.S. committed its military to protect fellow members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Just months later, Russia detonated its first atomic bomb, which began a lengthy nuclear arms race with the U.S.

In 1950, the doctrine of containing Soviet aggression led the U.S. into helping its Korean ally to beat back an invasion from North Korea. In 1962, the Navy confronted Soviet ships bringing missiles into Cuba. In 1965, U.S. Marines were sent to the Dominican Republic to fight communists, and 200,000 American troops went to fight the communist insurgents in Vietnam.

In time, America’s involvement in all these conflicts earned it the reputation of a global policeman. Countries inevitably looked to America when communist aggression arose anywhere in the world.

But after 42 years, the Cold War suddenly ended when the Soviet government collapsed in 1989. The threats of imminent war and nuclear attack were diminished, and generations were born who never knew air-raid drills, fallout shelters, or an active military draft.

But now, instead of one big adversary, we faced several smaller ones as the U.S. was assaulted by a variety of terrorist groups. America responded individually to the attacks on the World Trade Center (1993 and 2001), Federal Building in Oklahoma City (1995), and the Boston Marathon (2013).

America’s size and its military power were of limited help in defeating something as elusive and widespread as terrorism. An effort was made in Afghanistan in 2001 after that country refused to hand over the mastermind of the World Trade Center slaughter. That effort results in America’s longest war. It was ended discouragingly last July when American forces abruptly exited the country.

The message seemed to be: The world could police itself.

But that was before Russia invaded Ukraine. It seems we’re back where we left off decades ago, with Russia seizing free nations and threatening to use nuclear weapons. The Director of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation has said, “Ukraine is fighting a tyrant who is trying to glue the Soviet Union back together.”

Will we return to global policing?

Five years ago, Senator Tim Kaine said it was time to bring back the Truman Doctrine.

Speaking before the Brookings Institution, he said America has faced international problems without a governing doctrine. Issues are taken case-by-case, making it difficult to align allies with our diplomatic efforts.

If we have returned to a contest of superpowers, we may need a long-term, consistent strategy. But if the world’s democracies need a champion, should it be us?

Featured image: President Truman’s speech to Congress on March 12, 1947, which later became known as “The Truman Doctrine.” (Harry S. Truman Library and Museum)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Very informative.