When I ask Bill Bracken for his most poignant moment as a chef, he doesn’t gush about his former career in posh restaurants in Beverly Hills and Newport Beach, California, cooking for megastars like Tom Cruise and Sylvester Stallone. He tells me about a homeless woman named Ruby.

In 2013, Bracken had started a nonprofit, Bracken’s Kitchen, which feeds homecooked meals to the displaced, the old, the poor — “Anybody who’s hungry,” Bracken says. Ruby lived with other individuals in an encampment near the Orange County Civic Center, but Bracken had a problem.

“Homeless people scared me,” he admits. “I wasn’t scared physically. I was raised by a dad who taught me how to take care of myself. But for whatever reason, big, tough, bald Bill Bracken was scared.”

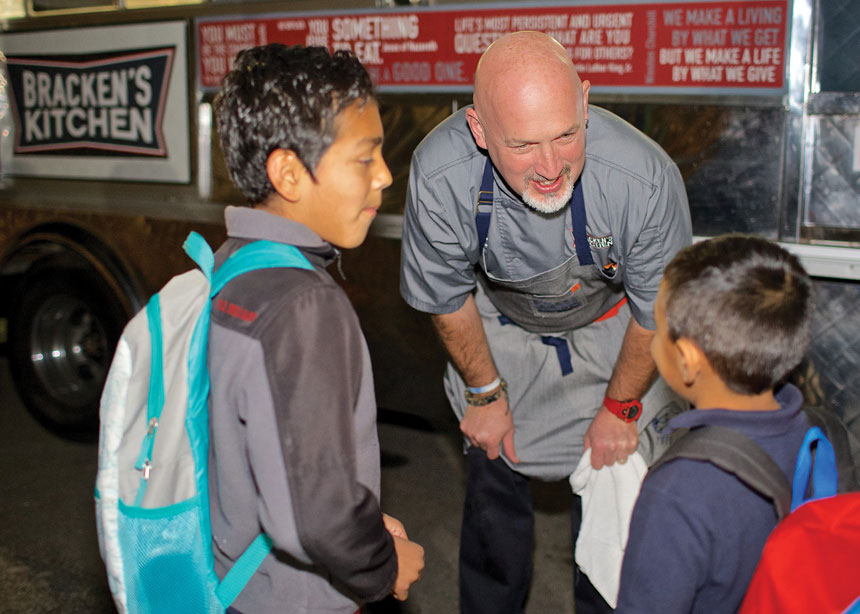

Bracken developed a Tuesday-night routine. He’d arrive in Betsy, his food truck, and honk the horn, and folks would rustle from benches and tents. Bracken would provide meals and then quickly withdraw. Slowly, however, he began to know his diners as individuals. James, John, and Toma. David, Luis, and Ruby.

One night, Ruby made a request. “Can I have a hug?” she asked.

Bracken panicked. But before he could retreat, “Ruby grabbed ahold of me and just hung on,” he says. “I don’t know if she hugged me for 30 seconds or two hours. But when she finally let go, right behind her was John. And behind John was James, Toma, and David. And I hugged them all.”

Bracken returned to his truck, dizzied by the experience. “I thought, of all the things she needed — a home, medicine, clothes — Ruby needed to know that someone cared about her. And that was such a pivotal moment in my journey. That’s the power of food. Just me showing up and not giving them a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, not handing them a bag of chips, but bringing a homemade meal made from love. We built a relationship.”

And that’s what Bracken’s Kitchen does every day: Fills empty stomachs, nourishes bodies and souls. In 2019, the organization prepared 8,000 meals a week. During the pandemic, it cooked 8,000 meals a day. In 2022, the organization served over 1.3 million meals via its two food trucks, volunteer delivery drivers, and more than 45 agency partners. How essential are these meals? In Orange County, where Bracken’s Kitchen works, nearly 400,000 people struggle with hunger.

“We’re in one of the wealthiest communities in America, yet one out of two kids don’t eat lunch at school without the government’s help,” he says.

Food has played a vital role in Bracken’s life since his own childhood, growing up the youngest of four kids in Wathena, Kansas, a farming community of about 1,200 people. When Bracken was 5, his mom returned to work. His older sisters rarely cooked, so he learned to fend for himself. “I made a mean goulash,” he remembers. “I still have Nestle’s Tollhouse cookie recipe ingrained in my brain.”

In high school, Bracken cooked at two restaurants, so the guidance counselor suggested he attend a vocational school after graduation. It made sense, though he lacked culinary role models. “The only chefs I really knew back then were John Ritter’s character on Three’s Company and The Galloping Gourmet,” he says. “This was Kansas. Back then, the mentality was that men don’t belong in the kitchen.”

A restaurant career seemed far-fetched, but after two years at vocational school, he earned a scholarship to the Culinary Institute of America. Bracken graduated at the top of his class in 1986 and worked with Four Seasons hotels in Dallas before transferring to California. Cooking for luxury hotels and high-end restaurants was exciting but exhausting. “The stress is crazy,” he says. “And I always knew that something was missing from my life.”

Then came the recession of 2008. Many of Bracken’s friends in the restaurant business lost their jobs. In 2011, Bracken was let go too. Looking back, he considers it an essential step in his faith journey. “I truly believe God has led me at every step,” he says, “and God was doing for me what I couldn’t do for myself,” pushing him from fine dining to his real calling: Feeding those in need.

Bracken’s Kitchen doesn’t just cook hot meals; it uses fresh ingredients that restaurants, grocery stores, and suppliers would otherwise toss in the trash. In 2022, Bracken’s Kitchen rescued 216 tons of food (it also bought 308 tons of food and received 151 tons of donations). According to the USDA, nearly 133 billion pounds of otherwise useable food are discarded in the U.S. annually, Bracken notes, more than any other country. He mentions a premier meat company, which sends prime beef to chefs worldwide, that recently donated 30 pounds of Kobe steaks to Bracken’s Kitchen. Why was such expensive beef available? The company couldn’t sell it, so they had to freeze it.

“Wolfgang Puck and all these famous chefs are never going to buy that piece of meat once it’s been frozen,” he says. “That type of food goes into landfills all the time. We’ve rescued 500 million pounds of food in the last five or six years. It’s crazy.”

Bracken’s Kitchen also trains young men and women to become chefs, a program that came from a moment of personal doubt. Shortly after creating the nonprofit, Bracken wondered if he’d made the right decision: Had he tossed aside his career — and spent a large chunk of his family’s savings — on an idea that might not work? But one evening, while feeding kids at an afterschool program for homeless children, he had an epiphany.

“I stood that night and looked around the patio,” he says. “Parents were eating — the kids had eaten and were playing — and it hit me that 30-40 years from now, those kids are still going to be here. The difference is that they’ll be adults, and it’s going to be their kids depending on a program like this. The cycle of poverty finally became real to me, and I finally understood it. How does a family escape that cycle when they have no chance of something better? No education, no training, no chance of going to college. And that’s when I realized, I’ve got to do something more.”

In early 2023, the organization’s culinary training program graduated its first test class. Two of its graduates are cooking in two of Orange County’s best restaurants, Bracken says. But he’s constantly reminded of the need to give more.

Bracken raises his phone and shows me a photo of a young boy, Mateo, and his grandmother. The night before, Bracken’s Kitchen had served the duo and about 180 other people at a local church. “They ate, they went home, they felt good,” he says. “But you know what? They woke up the next day and they were hungry. That’s how short-lived our work is.”

The culinary training program is the third branch of the organization’s “tree of service.” They feed people, they train people, they rescue food. Bracken enjoys collecting memorable quotes, which are the philosophical leaves on his humanitarian tree. One of his favorites comes from Mahatma Gandhi: “The best way to find yourself is to lose yourself in the service of others.” That’s exactly what Bracken, through the power of food, has accomplished with his life.

“I was one of those chefs who chased caviar and lobster and stars and diamonds because everybody wants to be a rock star. And it’s all meaningless. The work that we’ve done here,” he says, “this is what satisfies my soul.”

Ken Budd has written for The Atlantic, The Washington Post, National Geographic Traveler, and many more. He is the author of The Voluntourist. You can sign up for his newsletter about giving, travel, and amazing people at kenbudd.us.

This article is featured in the November/December 2023 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Bill, I also truly believe God led you to your true calling as well, feeding those in need. This is why your soul now feels satisfied, and will continue to in the times ahead.

This is LOVE in action. Well done and may there be many more “Bill Bracken’s” Thank you Bill and may you be blessed as you bless.