Today, Marjorie Merriweather Post is best remembered as the builder of Mar-a-Lago. That storied estate, the current home of former President Donald Trump, is only one symbol of Marjorie’s fairy-tale life. The breakfast cereal heiress was one of the wealthiest and most admired women of 20th century America, celebrated her for her beauty, art collections, and philanthropic gifts to charities, non-profit organizations, and needy individuals.

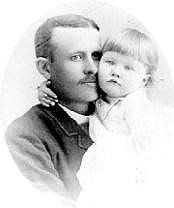

Marjorie’s origins were humble. Born on March 15, 1884, in Springfield, Illinois to Charles William Post and Ella Letitia Merriweather, Marjorie spent her childhood on a Battle Creek, Michigan farm. By then her entrepreneurial father, known as C.W., had converted to Christian Science after a long illness. Consequently, he believed that positive thinking and healthy foods were keys to wellness. Since he considered coffee unhealthy, he created a non-caffeinated drink made from roasted wheat bran and molasses, which he named Postum. As a child Marjorie remembered helping her father paste labels on the jars of his experimental drink. C. W. began advertising his other plant-based foods, Grape-Nuts (1897) and Post Toasties (1904) in newspapers and magazines; by the turn of the century, sales approached a million dollars.

During Marjorie’s youth, women still couldn’t vote, but C.W. resolved that his daughter must understand his business. With that in mind, he taught her to balance a budget, insisted she attend board meetings, and brought her on business trips across the country. Eager to have her become part of Eastern high society, he enrolled her in Washington, D.C.’s elite Mount Vernon Seminary for young women.

By then Marjorie was fabulously wealthy in her own right. As a child C.W. had given her shares of Postum stock which were worth $3 million by the time she was 16. Despite his daughter’s wealth, C.W. worried about her extravagance on clothes. In 1904, when Marjorie insisted upon buying new furs, he wrote, “You have more than double the clothes, shoes & stuff that any girl no matter how rich should have at 17. Now make some of the furs you have do & don’t order more dresses or clothes before you return….Dad wants you sensible, so go slow.”

C.W. then did something Marjorie considered even less “sensible” when he divorced her mother Ella and married his secretary and Marjorie’s part-time companion, Leila Young. A year later, 18-year-old Marjorie announced she intended wed Edward Close, a young attorney from Greenwich, Connecticut. Their wedding on December 5, 1905, made headlines across the country. One of the New York papers predicted that the Closes “will occupy a prominent position in the younger set for the bride is twice a millionaire. And the bridegroom is a descendant of one the oldest families in the metropolis.”

As a wedding gift C.W. presented the newlyweds with a large check and built them an 11- bedroom house in Greenwich, called The Boulders. At first all seemed well as Marjorie and Ed settled into marriage, followed in 1908 by the birth of their daughter Adelaide, and in 1909, Eleanor. But tensions already clouded the marriage. Ed disapproved of Marjorie’s belief in Christian Science and disdained her fondness for a lavish lifestyle. Marjorie was no happier with Ed, for she found Greenwich society stuffy and thought Ed drank too much. By then, too, C.W. realized that despite his hopes, Ed had no real interest in leading the Postum Cereal Company.

On May 9, 1914, shock waves broke over Marjorie when C.W., convinced he was terminally ill, committed suicide. Woodenly, the 27-year-old heiress attended the funeral rituals, but never got over her father’s death.

Fortunately, C. W. already had capable managers who continued to run the Postum Cereal Company profitably until the start of World War I. After the United States entered the war, Ed was drafted, and Marjorie began rolling bandages for the Red Cross to help the boys “over there.” Hoping to make a more significant contribution, she decided to fund an Army hospital ship bound for France. On July 30, 1917, as she and nine-year old Adelaide watched the camouflaged ship leave the harbor, it was inadvertently rammed by the S.S. Panama. Doctors, nurses, soldiers, and the crew were rescued from the sinking ship, but all the medical supplies were lost.

Marjorie would not be deterred. Eight days later she funded a second set of supplies, which were transported on the S.S. Finland to Savenay, France. There her donation helped establish the Number 8 Base Hospital, which became the largest Red Cross facility in wartime Europe. In 1957, France presented Marjorie with its highest civilian award, the French Legion of Honor. The establishment of the Army hospital also reflected Marjorie’s rapidly evolving personal philosophy: Women, especially wealthy ones, could exercise power by using their money for politically redeeming purposes.

Shortly afterwards, Ed returned from Europe, where he received a Medal of Honor from France. Nevertheless, his marriage to Marjorie foundered and ended in divorce. Several years earlier, she had been introduced to the newly-widowed legendary stockbroker, Edward Francis Hutton, known as E.F. Though short in stature, E.F. was handsome, a dashing dresser and such a gifted raconteur that in 1919 when Marjorie met him again, they fell in love. After their July 20, 1920, marriage, E.F. became the president of the Postum Cereal Company. Three years later Marjorie delivered her third daughter, Nedenia, the future movie star Dina Merrill.

In winter, the Huttons resided in Florida, where they were considered glamorous pacesetters for the “nouveau riche” society then rising in Palm Beach. After living there in several luxurious “cottages,” Marjorie decided to build a larger home where she could entertain in grander style. Ultimately, she chose 17 acres in a patch of jungle between Lake Worth and the Atlantic. After the plot was cleared of jungle growth, architect Marion Wyeth designed the floor plan with all rooms leading to a central courtyard.

Still, that didn’t satisfy the heiress, who wanted to create a home more unique than the other palatial mansions then rising along the shore. Through a suggestion from her friends, showman Florenz Ziegfeld and his actress wife Billie Burke, she engaged Joseph Urban, a Viennese architect and set designer, who enhanced Wyeth’s design by creating a crescent-shaped Hispano-Mooresque structure topped by a solitary tower. A large, circular patio served as the centerpiece for the 115-room estate. Named Mar-a-Lago from the Latin meaning “from sea to lake” the Huttons’ new home was completed in 1927 at a staggering price of $2.5 million. When friends expressed their fascination with the home, E. F. shrugged. “You know Marjorie said she was going to build a little cottage by the sea. Look what we got!”

Meanwhile, during the boom years of the Roaring Twenties, E.F. made drastic changes to C.W.’s old company. In 1923, he moved the headquarters of the Postum Cereal Company from Battle Creek to Manhattan and began diversifying its products. Among the companies he acquired were Jell-O, Swans Down Cake Flour, Minute Tapioca, Baker’s Chocolate and Log Cabin Maple Syrup. To reflect that expansion, E.F. changed the corporate name to the Postum Company. Despite Marjorie’s recollection of her father’s disapproval of coffee, E.F. added a competitor, Sanka. Still more upsetting was E.F.’s 1927 acquisition of Maxwell House Coffee since she had been raised with the idea that “coffee was just like taking dope.”

A few months later Marjorie made her own contribution to the Postum Company. One day while she and E.F. sailed their yacht to Gloucester, Massachusetts, their cook served them a delicious roasted goose. When she asked where he bought it, the cook said it came from a frozen food company owned by Clarence Birdseye. In that era, frozen foods were generally of a poor quality, so out of curiosity the heiress visited Birdseye at his company, General Seafood Corporation. There she learned that Birdseye had perfected a quick-freeze method for fish he had observed in Labrador practiced by the Inuit. Memories of the hours her mother Ella spent canning foods on the Battle Creek farm flooded over Marjorie, convincing her that Birdseye’s frozen foods would be a welcome product for the Postum Company.

“I’m speaking for the housewife here,” she told her husband. “Frozen foods will reduce her work considerably. It’s an opportunity we can’t afford to miss.”

E.F., however, claimed the idea was impractical since grocers would have to install freezers in their stores to sell it. “Believe me, Ned, they’ll buy the appliances. They’ll do it,” Marjorie insisted. Months passed as E.F continued to ignore his wife’s, pleas. Finally in 1929 he agreed to buy Birdseye’s General Seafood Corporation, even though the price had nearly doubled to $22 million. After the sale in July 1929 the name Postum Company seemed inadequate, so E.F. had it changed on the New York Stock Exchange to the General Foods Corporation.

Four months later in October, the stock market crashed. By then, the high cost of building Mar-a-Lago and disagreements over Birdseye’s frozen foods had already strained the Huttons’ marriage. Appalled by the onset of the Great Depression — with the rising unemployment of millions of workers, reports of men jumping from skyscrapers, and the rise of Hoovervilles, or tent cities, in big cities — Marjorie became so distressed that she resolved to help. Among her efforts was sponsorship of a charity ball at Madison Square Garden and leadership of a gifts campaign of the Salvation Army Women’s Emergency Aid Committee. She also stood at rush hour on the corner of Park Avenue and 46th Street to collect money from workers returning home for the Gibson Unemployment Relief Committee. The heiress also put her jewelry in a safe and used the saved insurance money to create the Marjorie Post Hutton Canteen for women and children.

E.F., however, thought little of her charitable acts, disapproved of Roosevelt’s relief efforts, and even criticized the president in an essay in the Detroit Free Press for “adopting as his own the rabble-rousing battle cry of ‘soaking the rich.’” Marjorie was aghast. That, combined with her discovery that her husband was sleeping with her French maid, finally ended the marriage.

Over the next four decades of her life until her death in 1973, Marjorie became one of America’s leading philanthropists who supported institutions such as the Red Cross, the Salvation Army, the Boy Scouts of America, the National Symphony Orchestra, and the future Kennedy Center for the Arts.

Yet today the most visible monument to her life is Mar-a-Lago, a reminder of an era of carefree glamour and majestic grandeur which has long since passed.

Nancy Rubin Stuart is the author of American Empress: The Life and Times of Marjorie Merriweather Post and other biographies about women. All quotes in this article are taken from the book.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Oh dear. What a shame that someone of such amazing philanthropy, kindness, drive and honesty is aligned with such a dishonest, power crazed corrupt individual such as Donald Trump just because of a house .

She is worth 100 times that man.

It is indeed an honor to the memory of Marjorie Merriweather Post that Mar-A-Lago is now inhabited by Donald Trump, who, other than Jimmy Carter, is the most honest, trustworthy and incorruptible man to hold the Presidency in the last 60 years at least, other than President Jimmy Carter. Thank you for the article.

Very good story. It recommends the book.

I like coffee.

Thank you Ms. Stuart for this in-depth feature on Marjorie Merriweather Post. She was raised with the right values, and her father got her on the right track teaching her and bringing her into the world of business at a young age. I even feel her self-indulgence in the furs, clothes and shoes at age 20 gave her the further empathy by contrast to those less fortunate, that would always be in the back of her mind as she helped those in need throughout her life.

Still, without her deep humanity and desire from within to help others, she could have just lived a life of luxury and privilege only. She had a lot to deal with that I’m sure was made more difficult just by her being a woman, wealthy or not. I hope she did get to enjoy the advantages she had coming her way. She deserved them.

As far a Mar-a-Lago goes, I’m sure she’d be shocked at the recent and current events it’s presently still embroiled in. But times change, and I personally would like her family own it once again; keeping the changes they like yes, but discarding the ones they don’t. I want to think Marjorie would love that for her estate also.

Marjorie definitely needs more than just Mar-a-Lago to honor her. I am very impressed with this article about her.