My first Christmas without my mother is a reminder of my first Christmas without. For all my earliest years, my mother made Christmas magical. But, by the time I turned 10, she also took it away.

Growing up in the 1970s, there were five of us in a small house in rural North Carolina – Mama, Diddy (as we called our dad), my older brother and sister, and me. We didn’t have much, but we had a console TV with a record player on top. For us kids, that’s all we needed.

Whether by choice or necessity, Mama oversaw everything Christmas: the tree, presents, putting greeting cards on a string to display, and giving the season its sparkle. This meant large colorful lights and drowning the tree in silver tinsel.

Diddy was a farmer. He worked from sunup to sundown. I don’t have a lot of memories of him at Christmas, but my favorite is the year he watched the Santa tracker with me. The local TV weatherman, Frank Deal – a lanky fellow with curly red hair – would chart Santa’s journey from the North Pole all the way to our little town, advising us when it was time to go to bed. As Santa grew closer, Diddy said, “Close your eyes or Santy won’t come.” I squeezed my eyes shut. I wanted Santa to see from waaay up there that I was asleep!

By 3 a.m. I couldn’t contain myself. I’d bound out of my room, rip open my presents, and play with everything at least once. Then I would pass out in the wrapping paper landfill. All before sunrise.

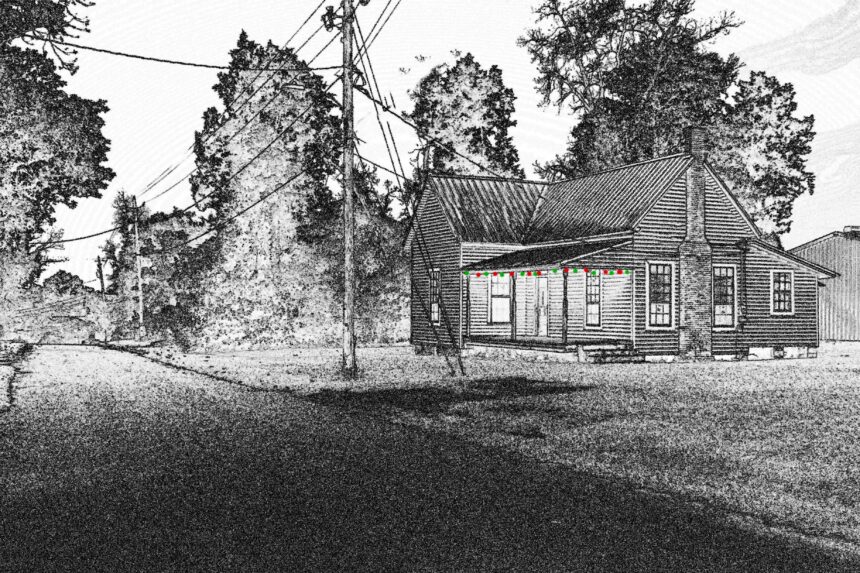

In 1981 when I was nine, Diddy moved out. We went from struggling to being among the “dirt poor” of Mama’s own youth. The thermostat went off and kerosene heaters went on, ones that seemed like they might set the house on fire at any moment, and left my nostrils filled with soot. In time, tarps and duct tape were all that seemed to hold the house together.

That first Christmas without my father, we couldn’t afford a tree, so I made one out of construction paper and taped it to the wall in our den. On Christmas morning, my sister and I emerged from our cramped bedroom to find one gift for each of us sitting on a recliner – identical jewelry organizers, a curious choice given that we had no jewelry. My brother received a statue of a bald eagle. None of the items were wrapped. There was no frenzy of tearing paper off. No exhaustion from playing with the toys we’d received. Mama slept in and we just went back to our rooms. I think we had known deep down this Christmas would be different; the money stress had been hard to miss. But we’d grown up with tales of Christmas miracles – surely one would come our way. The silence of tiptoeing around our sleeping mother and witnessing the gray stillness on that December morning sent us each into our own space to cry. We were hurt. We grieved – the best of our childhood was likely over.

Mama grew bitter. The money problems worsened. The following year, we stopped celebrating Christmas altogether. As a symptom of our decline, instead of watching holiday specials, Mama rented movies like The Town That Dreaded Sundown. I stopped dreaming of presents and started wishing for safe rooms.

The message I received was, once we were broke, we were broken.

As my siblings and I grew up and got jobs, we tried to “fix” the Christmas of our past with Christmas presents, pun intended. My brother worked and sacrificed to buy us our first VCR – at a time when it cost almost a thousand dollars. My sister would save all year, putting cash into a little white envelope to buy everything on our Christmas lists. Once I was making my own money, I tried to do every Christmas-y thing I could: host dinners, see all the light displays, send dozens of Christmas cards, go to every holiday concert, movie, and stage show (looking at you, A Very Die Hard Christmas), and, of course, go overboard with gifts – so many gifts for my friends, my family, for strangers in need! We thought if we had more of what we didn’t have as kids, it would make the holiday feel right again.

It never did.

My sister and mother died just months apart earlier this year. The double losses put me in a deeply reflective state on the meaning of things. Each time I went into a store, I was hit with a pang of loss – this year I wouldn’t be buying cards or gifts for either of them. It was in Staples, of all places, where I finally broke. Mama had loved taking me to get school supplies when I was young. We’d walk the aisles and she’d help me pick out paper, pens, and Trapper Keepers. She never rushed me. Instead, she’d tell me stories of what it was like when she was a kid – how she couldn’t afford to buy a copy of her class photo (back when they’d just take one picture of the entire room of students), so she’d sneak and take one of the unpurchased ones out of the trash. She’d had so little in her own childhood that she delighted in giving me more in mine. For the earliest years of my life, she’d been trying to fix what she’d missed out on, too. In that moment, next to stacks of notebooks I didn’t need but always seemed to buy, I sobbed. Mama and me – we weren’t so different. And all I wanted to do was tell her. I get it, Mama. I get it.

But I couldn’t tell her. I would never be able to tell her anything again.

In my grief, I finally realized what we lost so long ago. It wasn’t the Christmas stuff. It was the Christmas spirit. We had mistaken the garland and gifts for what mattered most. Hope.

Mama must have thought that when she couldn’t give us more than she’d had, there was no point in trying. I wish I’d known then what I know now: Mama, it wasn’t the presents that made us happy. It was you.

I have something now I didn’t have before: perspective. The best part of Christmas wasn’t the toys – my favorite thing I ever received was a complete set of Charlie’s Angels dolls, yet I soon destroyed them and buried Kelly in the backyard. (Sorry, Jaclyn Smith. Nothing personal.)

The magic was in watching Mama be happy. Creating memories I’d savor all these years later.

In the days leading up to Christmas, back when Diddy still lived with us, I’d eavesdrop as Mama took the receiver from the wall phone and its long cord and hid herself in the next room to order Barbies from the Sears catalogue. She would come home from stores like Kmart and our local chain, Roses, with loud, crinkly bags stuffed with treasures unknown. Sometimes she would surprise me early with a toy. “Give Mama sugar,” she would say and gesture for me to kiss her on the cheek.

Once the tree was decorated, Mama would take us outside. She wanted to see how it looked through the window to neighbors and passersby. And on the rare occasion when it snowed, she’d beckon us out into the cold to share in her sense of wonder. When I moved to Southern California in 1998, she would keep snowballs in the freezer for me to come home to.

As the years went on, my mother became mercurial. Difficult. Even downright mean. On the one hand, she might tell me, “You don’t have the good sense God gave a billy goat.” On the other, she would Fed Ex me Krispy Kreme donuts when I moved to a state that didn’t yet have them. She was capable of flying into a rage and breaking gifts we’d given her, but then she would have a change of heart and try to make a joyful shopping trip out of going to Wal-Mart to get “a better one.”

Eventually, I pulled away. I had to stop engaging with the negativity – I got a separate phone line just for her calls. It was my “scary phone” that off-loaded her rants into the voicemail ether. As a good Southerner, I never stopped loving my Mama, even if I didn’t always like her.

Our family home rotted and fell apart, and so did Mama. The house and her own cognitive decline put her at risk, so she was forced into a nursing home by the state. After suffering from dementia, she died in June. At her funeral, my aunts, uncles, and I joked that the cracks of thunder outside were “Mama having the last word.”

Before she passed, I visited her in the memory care facility. Her eyes were cloudy with age and confusion. Gone was her rage. In its place was the Mama of my youth. A tiny wisp of a woman with a beautiful head of hair. Perfectly curled. She didn’t recognize me. But she lit up like a child at the sight of my two Pomeranians. She held them as if they were her own. She kissed on their heads just as she’d done to me as a child.

It was as if I was being granted an early Christmas wish – a little taste of the miraculous. Mama was the nicest she’d been since I was young, watching her scoop up snow in her mitten-covered hands.

At one point she looked at me and said, “You seem like a sweet girl. Your mama must have done a good job raising you.”

Yes, Mama. You did.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I don’t remember very many details about the good Christmas’ as you do, but I do remember moments. Moments when I saw my mother and father standing arm-in-arm watching my brother and I open and enjoy our Christmas gifts. But the feeling I had was confusion. They had been fighting and yelling for a long time, like they hated each other. And yet here they were, standing there smiling with loving faces, holding each other, while I investigated my new bicycle.

That was the last time I remember them together.

Born out of that failed relationship was my mother’s lifelong struggle to forgive, to trust again. Her purpose became a nonstop, almost a craving, to loathe and hate and resent. Even me.

She died the day after Christmas. I hadn’t seen her for over 10 years. I hadn’t missed the innuendos or mentions of others who, in her obvious opinion, were excelling in their careers much faster than me; but I did miss the occasional laughter and smiles. Mostly, I felt pity for her.

Amazing essay! Sat post please keep posting this author ❤️

As someone who knew your mother and the heartbreak you experienced and continue to feel, this story brought me to tears, again.

I’ve known you since I was 15 and knew your family history but yet would always ask myself, “how did Pati end up so sweet?” There are many miracles in your story but the greatest to me is sharing it. You’re able to light a path so others can see how to negotiate the love of a mother who may not like or love us in the ways we expect moms to or the sudden absence of a father who should be there to protect and guide us.

Your scary phone was always remarkable to me because it seemed like you were still offering a lifeline to your mother, a therapy of sorts that while it soothed her, terrorized you.

Thank you for making your story public, offering us therapy too in the sweet way you’ve always done.

What a bittersweet story. I am glad your mom tried so hard to make wonderful Christmas memories for you & your family, & so sorry you went thru such hard times when your Dad left. One of the things I really struggle with is how men can completely abandon their children, both emotionally & financially. I am so glad you were able to re-connect with her & (accidentally!) bring her great joy near her end of days on this earth.

Thank you for sharing your own personal story here, Patricia. My condolences on losing both your mother and sister just months apart, earlier this year. That’s very rough, even if mom was in late-stage dementia. I’m glad your last memories with her though were reminiscent of your youth, and the version of her from so many years earlier.

It’s hard when your parent no longer knows who you are. Still, there was a connection there to YOU, even if facilitated by the dogs, from her kind words at how your mama must have done a good job raising you, not realizing she was actually talking about herself.

I lost my mom 10 years ago this week (12/20/13) from Parkinson’s but didn’t get that nice, final memory I’m glad you did. The breathing machine, tubes, seeing her so helpless; all I could do was tell her what a great mom she was, how much I love her, and it’s okay to let go. I barely left the room without losing it completely, and was in a bad way driving home. That visit was December 13th. I tried to go out there over the next week, but was told she was sleeping when calling in advance first over the next week. I now think God didn’t want that for me again.

You’re so right about the fact it’s not the physical gifts that matter. It was your bonding time with your mother year round, seeing her happy, not just at the Holidays, that will always stay with you, and get you through the bouts of sadness when they happen, I promise.