Maestro

⭐️ ⭐️ ⭐️ ⭐️

Rating: R

Run Time: 2 hours 9 minutes

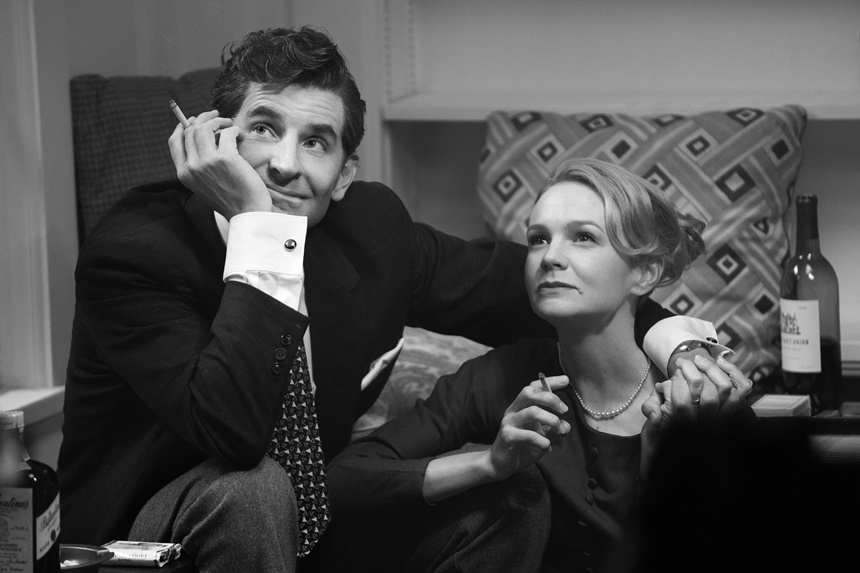

Stars: Carey Mulligan, Bradley Cooper

Writer/Director: Bradley Cooper

In Theaters and Streaming on Netflix

In what can best be described as a meeting of mega-hyphenates, director-writer-producer-star Bradley Cooper plunges head-first into his brilliantly envisioned, impeccably realized biography of composer-conductor-pianist-teacher Leonard Bernstein.

Portraying Lenny from his 20s through his late 60s, Cooper defies anyone else to inscribe their name on Oscar’s next Best Actor statuette — and makes a darned good case on behalf of his costar, Carey Mulligan, who sears the screen as the composer’s conflicted yet fiercely devoted wife, Felicia Montealegre.

The Hollywood Freeway is littered with the hulks of well-intentioned vanity projects that crashed and burned: Witness, if you dare, John Travolta’s Scientology epic Battlefield Earth or Kevin Costner’s apocalyptrocious The Postman. Cooper’s determination to do right by Lenny is as plain as the prosthetic nose on his face, and while he is, indeed, guilty of all sorts of cinematic self-indulgence here, he pulls it off while channeling his subject’s own legendarily ferocious complacency.

In tracing Bernstein’s long career, Cooper evokes the film styles of each successive era. After a brief prologue of Lenny near the end of his life, the screen narrows to 1940s dimensions and the image shifts to black-and-white. That would seem a too-cute-by-half affectation, but in moments it’s clear the constellation of show biz folks in Lenny’s orbit see themselves as characters in a Preston Sturges screwball comedy — exchanging self-consciously clever banter at impossibly cramped, smoke-choked cocktail parties; breaking into spontaneous song; sneaking off for the occasional romantic tete-a-tete.

At one such gathering, Lenny — already the toast of New York — finds himself infatuated with the Costa Rican-born Felicia, a struggling actress with big dreams. The feeling is mutual, and why not? He’s a wide-eyed, pearl-toothed charmer; she’s a whip-smart, slightly mysterious beauty clearly on the rise on Broadway. Soon the pair are going everywhere together, sharing private jokes and loving looks, the perfect show biz matchup.

Of course, from the outset we know something Felicia does not: Lenny is already in a romantic relationship with clarinetist — and future Columbia Masterworks producer — David Oppenheim (Magic Mike’s Matt Bomer). As screenwriter, Cooper never offers us a moment when Felicia discovers Lenny’s double life of flitting from one male lover to the next, and that may be for the best: The decision allows Mulligan to swath Felicia’s growing awareness in a veil of vaguely emerging acceptance. As the years go by — and the film turns to color and the screen frame widens — Felicia lulls herself into an uneasy truce with the forces tugging at her marriage.

That is, until Lenny starts to get, as she puts it, “sloppy.” It’s bad enough when she finds Lenny canoodling with a young male admirer in the hallway during a party. But when their teenage daughter Jamie (Maya Hawke) returns from a summer at the Tanglewood music school with rumors about her dad’s sexual adventurism, a full-blown family crisis arises.

There are a good half-dozen scenes in Maestro that allow Cooper to go Full Lenny, fairly exploding from the screen with Bernsteinian bombast. But perhaps his best moments are the more quiet ones, like when Lenny sits on a porch, trying to convince his daughter — on his wife’s stern order — that the Tanglewood stories are a lie.

“I’m glad,” she says. And we see in Cooper’s face something of an acting miracle: Lenny’s relief that the girl is buying his ruse; and the soul-deflating realization that his daughter is happy to hear that her father is not the man that he actually is.

A curiosity regarding Maestro is Cooper’s decision — through much of the film’s publicity and in giving Mulligan top billing — to suggest Felicia is actually the film’s central character. Certainly, Felicia emerges as the essential muse in Lenny’s life, but the script actually sells the real Felicia short. She was much more than a successful TV and stage actress: A passionate anti-war activist of the 1960s and early ’70s, Felicia was arrested on the steps of the U.S. Capitol in 1970. And, as the recent Netflix documentary Radical Wolfe recalls, it was Felicia who threw a notorious 1970 party at the Bernstein’s apartment to raise money for 21 imprisoned members of the Black Panthers (gatecrasher Tom Wolfe was inspired that night to coin the term “Radical Chic”).

In some ways, the last third of the film does belong to Mulligan, portraying Felicia as she battles spreading breast cancer. Surrounded by her children, reconciled with Lenny, Mulligan’s Felicia is a woman saddened that her life is ending too soon (at 58), but heartened by the fact that she will forever remain an essential ingredient in so many lives.

As memorable as Maestro is as a whole, the sequence that will follow you for weeks is one that comes near the end of the film, as Lenny conducts Mahler’s Resurrection at Ely Cathedral. It’s a legendary moment in 20th century music history: You’ll find the entire original concert on YouTube, and it is clear Cooper studied every frame of Bernstein’s performance: that great head of hair flying, the rivulets of sweat on his brow, the conductor nearly bursting from his tuxedo, the Incredible Hulk of classical music.

As the final notes echo through the cathedral, Cooper’s Leonard Bernstein remains reverently bowed, as if having just offered a benediction. There should be an explosion of rapturous applause, but instead the audience remains silent, awestruck. It takes an eternity of seconds for someone to finally clap, and then comes a tsunami of appreciation.

Well, I told myself, that was a bit over the top, wasn’t it? A cathedral full of music lovers forgetting to applaud?

Check out the YouTube video, and you’ll see. As always in his landmark passion project, Bradley Cooper gets it just right.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thank you, Kathryn! I get your point about complacency— the point I was trying to get across was that Lenny was quite comfortable with the notion of being a genius, despite his inherent insecurities. Quite a contradiction, and it gave him no end of heartache.

Mr. Newcott; It is so lovely to read a review by a true writer of the English languge. I fume often over content

out there on the Internet. So thank you for such a readable piece.

I do contend with one comment you have made-that Leonard Bernstein was legendarily ferociously complacent.

Having followed his work since I was a young musician of 8, I would say there was not a complacent bone or nerve in his body.