William Stout was just three years old when his parents took him to see his first movie — a rerelease of the 1933 version of King Kong — at a drive-in theater in Reseda, California. From the backseat of the family Ford, Stout watched, saucer-eyed, as dinosaurs rampaged and Kong battled for Fay Wray’s affection, every moment made more dramatic by Max Steiner’s evocative score.

To say that King Kong changed Stout’s life would be an understatement. The movie instilled in him a fascination with dinosaurs that would later make him one of the most respected paleo artists of his generation. His first book, The Dinosaurs: A Fantastic New View of a Lost Era, was an inspiration for Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park, and his paintings and murals of prehistoric life can be found in museums of natural history throughout the United States. Stout’s introduction at age three to the magic of motion pictures also led to a career in the film industry as a storyboard artist, set designer, concept designer, and creature designer on such films as Men in Black (1997), Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), and The Prestige (2006).

Stout wouldn’t learn until much later that the movie he had watched that warm summer evening in 1952 was not the version that had terrified audiences on its initial release 19 years earlier. The version Stout saw had been edited to remove scenes subsequently deemed too horrific or risqué, such as Kong eating an island native and crushing another under his foot, and Kong removing Ann Darrow’s dress and dropping another woman to her death from a Manhattan skyscraper. This was the version shown on television for decades.

Stout was in his 20s when he finally saw King Kong with the missing scenes intact, though they were of poor visual quality. Years later, film restorationists were able to clean up and sharpen the controversial scenes, along with the rest of the film, for a theatrical and home video release. At long last, Stout was able to watch King Kong as originally intended, as crisp and clear as the day it premiered. “It was exhilarating and gratifying to finally see a high-quality version of those scenes properly reinserted back into the film, where they belong,” Stout observes. “King Kong is still my all-time favorite movie. I’ve watched it at least 60 times.”

King Kong is just one of a long list of motion pictures that have been rescued, restored, and preserved through the painstaking efforts of film restorationists and archivists around the world. But their work is far from done. Thousands of films, including many that are just a few decades old, are still in danger of disappearing forever.

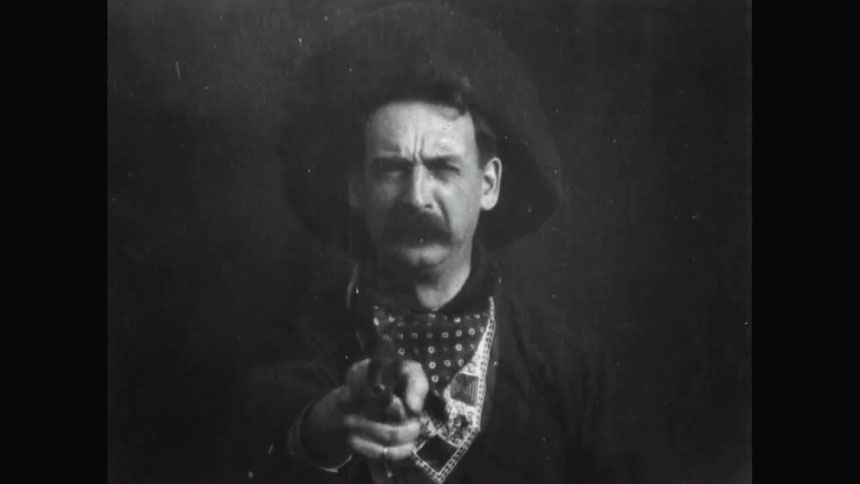

Motion pictures have been entertaining audiences since the late 1800s. Thomas Edison, working with his assistant William Dickson, created an early motion picture camera called the kinetograph in 1890, and a projector, known as a kinetoscope, two years later. Other inventors, such as French filmmakers Auguste and Louis Lumière, also helped advance the artform in significant ways. Within two decades, motion pictures would become one of the most popular forms of public entertainment in the world.

Unfortunately, very few of those early motion pictures still exist. “More than 90 percent of early silent films have been lost due to fire, poor storage, or other factors,” reports James Mockoski, a film archivist and restorationist with Francis Ford Coppola’s production company, American Zoetrope, who works on other restoration projects on the side. “It’s a radical loss.”

One of the greatest factors in the loss of early motion pictures is the nitrocellulose film stock in use at the time. Developed in the late 1800s, nitrocellulose, also known as cellulose nitrate and the once-trademarked term celluloid, breaks down and becomes extremely combustible if not stored under cool, dry conditions. As a result, theater fires were common during the early days of cinema, as were storage vault fires in later years.

“Into the early 1950s, almost every commercial movie was photographed on nitrate film,” says Robert Harris, a restorationist with The Film Preserve, an organization that researches, preserves, and restores motion pictures. “Very simply, it’s transparent gunpowder. It can catch on fire very easily, and will continue to burn even if you put it in water.”

When properly stored, nitrate stock can last a long time. The camera negative of the 1903 version of The Great Train Robbery stored at the Library of Congress, for example, remains in excellent condition. But poorly stored movies shot on nitrate stock are disasters waiting to happen, and many historically important motion pictures have been lost forever as a result of storage vault fires, Harris notes. In 1978, for example, the auto-ignition of nitrate film stock at two important film archives — the United States National Archives and Records Service (now Administration) and George Eastman House (now known as the George Eastman Museum) — resulted in the loss of more than 300 original film negatives and millions of feet of newsreel footage.

A safer stock made of cellulose acetate plastic came into use in the 1950s. It wasn’t flammable like nitrocellulose stock, but it had its own issues, including a tendency to shrink and degrade if not properly stored, a phenomenon known as vinegar syndrome because of the sour smell it produces. The film’s gelatin emulsion becomes brittle and starts to buckle and, if not addressed in time, can make the film almost impossible to unspool without causing extensive damage to the images.

Another reason so many early films are no longer available is that many studios simply threw them away once they had outlived their show value. “Film was an ephemeral medium,” observes Mockoski. “Movies were made to be shown in theaters until they were run to death, and then it was on to the next film. There was no secondary market as there is today.”

According to Jillian Borders, head of preservation at the UCLA Film and Television Archive, studios — fearing the risks of keeping nitrate film — often disposed of their early movies by dumping them in the ocean. “The Paramount Pictures Nitrate Print Library collection came to the UCLA Film and Television Archive at the beginning of its founding because it was about to be disposed of,” Borders says. “Some say the films were on the docks ready to be dumped when they were taken in by the Archive, but that might be an exaggeration. In many cases, the films had been previously copied, perhaps poorly, onto acetate stock, so it wasn’t a full-scale dumping of unique material. It’s possible that other nitrate films were destroyed by burial or some other method and not all of it went into the ocean.”

The film preservation movement has a long history. In fact, dedicated efforts to protect and preserve motion pictures date back decades. Scott MacQueen, who oversaw the restoration of the Disney film library and directed the restoration program at the UCLA Film and Television Archive until his retirement in 2021, points to the vital work of British film critic Iris Barry. In 1935, Barry was appointed curator of the Museum of Modern Art’s new film library, the first in the United States. “Barry began collecting what she felt were signal events in American film,” MacQueen reports. “She commissioned prints of movies from Universal Pictures, for example, that she felt were important, such as Blind Husbands (1919) by Erich von Stroheim and Sunrise (1927) by F.W. Murnau. That library became the foundation [of film preservation] in America.”

French film archivists Henri Langlois and Lotte Eisner established the Cinémathèque Française, an important archive dedicated to making movies available to all, in 1936. At the start of World War II, Langlois, who owned one of the largest film collections in the world, successfully smuggled numerous significant motion pictures out of Nazi-occupied France to save them from certain destruction. Meanwhile, in England, Ernest Lindgren curated the British Film Institute with an emphasis on preservation. Over the years, numerous other archives have been established around the world, creating a network that works across borders with the common goal of restoring and preserving the world’s cinematic treasures.

The United States boasts several important film archives, with the Library of Congress holding the largest collection. That archive was established because early filmmakers commonly sent a copy of their films to the Library of Congress to establish copyright. The George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York, houses another notable film collection, as does the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Film Archive and the UCLA Film and Television Archive, just to name a few.

UCLA’s early preservation work was initiated by Preservation Officer Robert Gitt starting around 1978, says Borders. Today, the school’s Film and Television Archive comprises 350,000 motion pictures, 170,000 television holdings, and more than 27 million feet of newsreel stories from the Hearst Metrotone News Collection, one of the largest newsreel collections in the world. History buffs can access 15,000 of the newly scanned newsreels at newsreels.net.

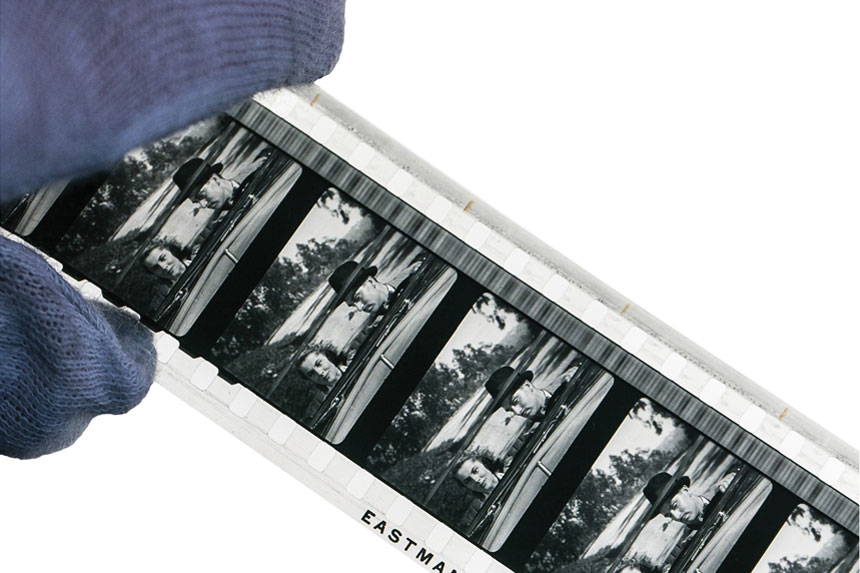

Film restoration is a painstaking endeavor that requires restorationists to be both detective and artist. The films they work on may suffer from a variety of issues, including dirty, washed-out prints; degraded film stock; deleted scenes; and missing negatives, soundtracks, or other necessary elements.

The detective work occurs first as restorationists scour studio vaults, film archives, and notable private collections throughout the world for specific elements that can be used to replace those that are missing or damaged. The process can be time-consuming. In 2009, Gitt examined more than 200 reels of the 1948 drama The Red Shoes to find the best surviving materials. MacQueen recalls that he and his team relied on five different archives, including one in Australia, to find the elements needed for the restoration of the 1953 science-fiction classic Invaders from Mars, a project that took a year to complete.

Advances in technology have helped restorationists immensely. Film elements are now commonly scanned and turned into digital files, which are cleaned and color-corrected via computer. Computers also play a role in editing a film as it is restored, digitally replacing damaged scenes as needed, or restoring previously edited scenes in an effort to return a film to the director’s original vision.

“Digital is the best thing that’s happened to film restoration,” says Harris. “It enables us to do things on a much lower budget without losing a generation. If you’re scanning a camera negative, what you’re putting on screen is going to look exactly like that camera negative.”

When possible, restorationists prefer to work in conjunction with a film’s director and others involved in its creation. Such was the case in 1991 when Harris oversaw the restoration of Spartacus (1960). Director Stanley Kubrick and producer/star Kirk Douglas were both involved in the project, eager to see the gladiator epic restored to its original glory. Some scenes, including one involving Laurence Olivier and Tony Curtis, were missing the dialogue soundtrack, requiring the dialogue to be re-recorded. Curtis was available to record his part, but Olivier had passed away. Harris was advised to contact actor Anthony Hopkins, who was known for his spot-on Olivier impression. Hopkins happily revoiced Olivier’s lines, adding much to the restored film.

Harris also led the mid-’80s restoration of Lawrence of Arabia (1962) to its original 70mm format, a project that took more than two years to complete. Harris was unsure what elements would best inform the restoration, and reached out to Anne Coates, who had edited the film with director David Lean. Coates put Harris in touch with Lean, who viewed a rough cut that Harris had put together. Lean noticed that Harris was missing about 20 minutes of sound and offered to bring together the actors who were still alive to re-record their dialogue. “It was at that moment that the project went from my reconstruction to our reconstruction,” Harris says.

Older big-studio films are understandably a primary focus of preservationists, but not their only focus. The works of many independent filmmakers who worked outside the studio system, student filmmakers, and avantgarde directors are also in a race against the clock.

There is also a growing effort to restore and preserve relatively recent films, adds Mockoski. “Loss is not something specific to the silent era,” he says. “There are movies made just 20 or 30 years ago that are on the verge of disappearing or have disappeared. In some cases, no one even knows where the negative is or who owns the rights.”

Locating the needed elements to properly restore a motion picture is just one of the many challenges faced by restorationists. An equally vexing problem is funding, which Borders calls “a perennially major issue” because film restoration can be costly. And then there is the issue of technological change. “Film is dying,” states MacQueen. “Thirty-five-millimeter celluloid is going away, and Kodak has cut down on the numbers and types of film stock it produces. With the transition to digital cinema, film has become a very endangered commodity.”

Of course, no medium lasts forever. Many believed early on that digital preservation, in which a movie is saved as a digital file and stored on a hard drive, would be film’s savior. However, even that format has a finite life, MacQueen notes; movies must be migrated to new hard drives every few years to ensure that the files don’t become corrupted.

The efforts of film restorationists are deeply appreciated by a growing subculture of movie fans who revel in the old made new, especially exploitation films — quickly made low-budget movies hoping to cash in on trends or the sensationalization of sex and violence — and other nonmainstream fare. Vinegar Syndrome, a niche restoration and distribution company based in Bridgeport, Connecticut, has made such fare its bread and butter, having salvaged dozens of titles ranging from Psycho Girls to Ninja in the Claws of the CIA.

Never heard of them? You’re not alone. But their restoration and rerelease were cause for celebration among die-hard exploitation fans, such as film historian Robin Bougie, publisher of the review zine Cinema Sewer, which published its 36th and final issue in 2021.

“What draws me into indie movies or stuff outside the mainstream is there’s an element of danger and creativity that is promised by them that I don’t see as much from corporate-made art,” Bougie explains. “There’s a chance you’re going to experience something you’ve never seen before. It may not be something ‘good,’ which is subjective at best, but at least it’s a possibility of something unique.”

Bougie says 1984’s The Terminator, written and directed by James Cameron, was his introduction to the world of exploitation films. Once hooked, he never looked back. “Seeing The Terminator as a kid really changed me,” Bougie notes.

There is tremendous debate over whether all movies, regardless of quality, deserve to be restored and preserved. At the heart of the issue: What do we as a society lose when a film is lost forever? Why are restoration and preservation important?

“When a movie is lost, it feels like we’re losing the historical record,” observes Borders. “We still have books about their period, of course, but there’s something tangible about a moving image of the way life used to be, or the way life was portrayed to be. We also lose the cultural record of what people were thinking and doing at the time the movie was made, what it gave the audience, such as happy musicals during World War II.”

Mockoski agrees, concluding, “Many films were made within a social context that helps us understand what was acceptable then and what may not be acceptable now. It helps us understand where we came from.”

Don Vaughan is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in Writer’s Digest, Mad, Scout Life, and elsewhere. In the November/December issue, he wrote about the National Christmas Tree. To learn more, visit donaldvaughan.com.

This article is featured in the January/February 2024 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

thank you all, so much! im a baby boomer, love movies, have great love/respect for the past. several ronald colman films were lost, destroyed, damaged. he was yuuge in silent films, before talkies—the first to be able to act And speak meaningfully when talkies arrived.

colman introduced the moustache to all movie heroes—flynn, fairbanks, powell, etc!

i worked at the library of congress in the early ’70’s, music division, which at that time, also housed all the film archives. it was such a privilege to become familiar with the budding technology of preserving film! ( along with recordings, which had also been left to spoil.)

thank you again for this interesting and invaluable article, as well as the comments of your readers! i had goose bumps the entire time…

Mr. Stout was probably lucky (at only 3) seeing the censored version of ‘King Kong’ which was made right before the Hays Code went into effect in 1934. Glad though he got to see it years later painstakingly fully restored by film restorationists, with the removed scenes reinserted.

It’s scary to think most commercial films even into the 1950s were photographed on nitrate film; basically transparent gun powder, until the non-flammable cellulose acetate plastic replaced it, but not without different problems. It’s kind of shocking movies made 20 or 30 years ago (like ‘Chaplin’) are at risk too. Even films saved on a digital file and stored on a hard drive must be migrated to new ones every few years in order to be further saved.

Films at their best, are a unique art form that must be preserved. We need them as a way to time travel, as no other medium throughout history ever existed to allow this until the late 1800s. It’s worth the time and sacrifice. Fortunately, many films over the past 35 years are strictly interchangeable CGI/pyrotechic “product” made for quick profits overseas, making those NOT to preserve, easy stand-out choices.