Fifty years ago, two novels were published that would have a significant impact in an unexpected genre boom. One was set on land, and the other would eventually ruin beaches for many people. They were James Herbert’s The Rats and Peter Benchley’s Jaws, and they would be part of a ’70s wave of animal-driven natural horror.

A story of “animal gone bad” wasn’t new in the ’70s. Edgar Allen Poe and H.G. Wells did it in literature. Hitchcock had done The Birds in 1963 (based on the 1952 Daphne du Maurier story). 1942’s live-action Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book had multiple animal antagonists, including a tiger. Of course, there’s Godzilla (1954), Willard (1971), and so on. However, two things that the Watergate decade had going for it on screen was a marked increase in the quality of special effects and a thriving disaster genre that had room for a furry (or scaly, or chitinous) subgenre.

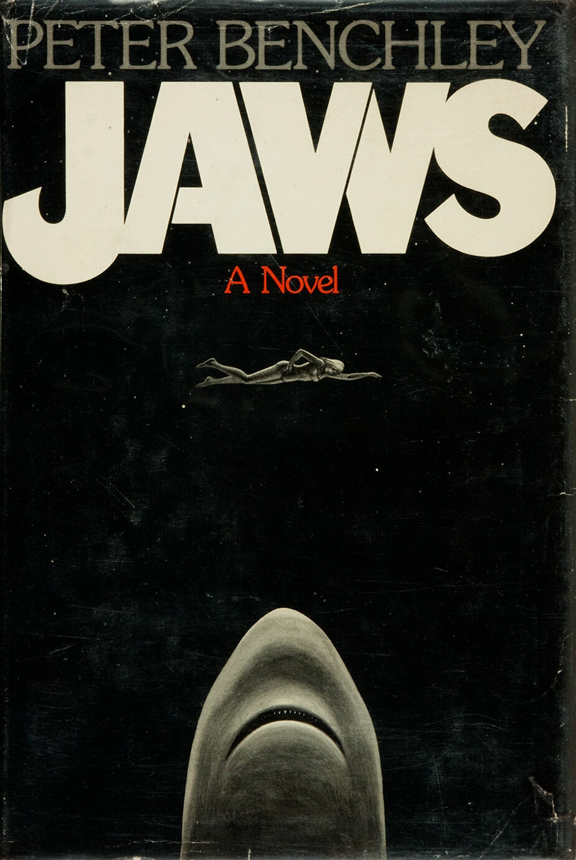

Fifty years ago this month, Peter Benchley published Jaws. Benchley had a remarkable background and an eclectic career prior to penning the bestseller. His grandfather, Robert, was a founder of the famed Algonquin Round Table, and his father, Nathaniel, wrote 16 novels and twice as many children’s books. Peter Benchley graduated from Harvard, wrote for The Washington Post, and served in the LBJ White House as a speechwriter.

A report of a fisherman landing a 4,500-pound great white shark in 1964 planted a story seed in Benchley’s mind, and he eventually made the deal to write his story, Jaws, for Doubleday. The book was huge, spending 44 weeks on the bestseller lists as a hardcover. When the paperback dropped the next year, it sold millions. It wasn’t long before the book was headed to the movies in the hands of a young director named Steve Spielberg.

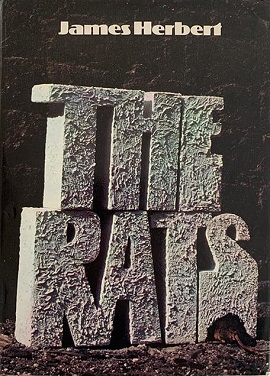

Across the pond in England, also in 1974, a novelist was about to see his first book published. James Herbert started out in advertising after a stint in art school. New English Library published The Rats, a fast-moving horror novel about a plague of rat attacks in modern England. The novel drew some sharp criticism for its graphic imagery, but it was popular and attracted support from star writers like fellow Brit horror specialist Ramsey Campbell and genre master Stephen King. In his nonfiction book Danse Macabre, King devotes several pages to discussing Herbert’s work and calls Herbert “probably the best writer of pulp horror to come along since the death of Robert E. Howard.” The book launched Herbert on a long horror career that included three direct sequels to The Rats.

The original Jaws trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Rotten Tomatoes Classic Trailers)

When Spielberg’s film adaptation of Jaws surfaced in 1975, it rewrote the history books. Despite a production troubled by a glitchy mechanical shark nicknamed Bruce, Spielberg brilliantly worked around the issues by taking a “less is more” approach in terms of the shark’s actual screentime. The cast and crew also had to contend with all the problems that come with shooting on the actual ocean, resulting in dramatic cost overruns. It didn’t matter. Jaws demolished box office records and turned the summer into the home for movie blockbusters. The mostly positive reviews praised the cast, Spielberg’s particularly effective direction, and the suspenseful score of John Williams. Already a massive hit, Jaws was nominated for Best Picture and won three other Oscars (Best Sound, Best Original Dramatic Score, Best Film Editing); it would only grow in reputation, eventually being acknowledged as a true film classic.

The Orca trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by ScreamFactoryTV)

You know Hollywood. It in the wake of Jaws’s success, every studio large and small needed attacking animals. More than 20 more animal horror films hit the screen between 1976 and 1980. Every part of the animal kingdom was represented. From the waters came the likes of Orca (1977), Tentacles (1977), and Piranha (1978). Insects and arachnids arrived in the form of The Savage Bees (1976), Empire of the Ants (1977), Kingdom of the Spiders (1977), The Bees (presumably also savage, 1978) and The Swarm (1978). Reptiles and amphibians got in on the act via Rattlers (1976), Frogs (1976), and the movie that combined animal horror and urban legends about people flushing reptiles into the New York sewers, Alligator (1980). Even invertebrates got a mention with Squirm (1976).

But the greatest concentration of animal horror came from mammals. While there had been earlier antecedents like the big bad bunnies of 1972’s Night of the Lepus and 1973’s Pigs, post-Jaws killer mammals came in droves. There were rats, H.G. Wells-style (Food of the Gods, 1976), Grizzly (1976), Dogs (1976), The Pack (1977), the rather inclusive Day of the Animals (1977), the bats of Nightwing (1979), and Prophecy (1979).

Prophecy trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by ScreamFactoryTV)

Prophecy said out loud what a fair number of the films implied. Certainly subtext (or completely unsubtle text) suggests that the cause of most of these animals attacking is people messing with nature. In most of the films, the horror is kicked off by humans spoiling habitats or an experiment gone wrong. That overarching idea gelled with the ecological awareness that had boomed in the ’70s and merged with the already-successful disaster genre. In some cases, audiences felt sympathy for the animals and may have even rooted for them to get even. King devotes a few pages to Prophecy in Danse Macabre, and he notes how overt some of the social concerns were (even ahead of their time) as local Native Americans (whom King wryly notes weren’t played by actual Native Americans, making King waaaay ahead of his own time) were protesting industrial pollution, and the Evil Executive gets dispatched by the mutated bear monster near the end.

Despite the fact that there might have been messages in the movies, it’s also pretty clear that we had a run in the 1970s of audiences simply enjoying watching animals get revenge. Obviously, that’s never gone away. Herbert’s The Rats eventually got made as Deadly Eyes (1985), King himself gave us Cujo, there have been six-and-counting Jurassic Park films, and so on. Since humans never stop messing around with nature, there’s plenty of story material out there for ideas of how nature might mess back. Like all booms, the disaster genre and animal attack genre receded as the ’80s moved into big cycles of science fiction, fantasy, and teen comedies. But for a while, nothing was scarier than going to the beach, or camping, or to the zoo, or to the New York sewers . . . well, that will always be scary.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

The majority of these films are ridiculous and strain any normal person’s credulity. This is just my opinion and I don’t think anyone should take it as gospel. A lot of the various saccharine media outpourings and offerings will continue to resonate with the general public who will spend their money on things they like. I have no desire to take that away from them.

Yes, shark attacks happen but Orcas pose no threat to humans. We pose more of a threat to both of them than they to us.

Cocaine Bear – the bear died from a cocaine overdose in the area of contact and never harmed anyone.

Then there’s all the wannabes like cocaine cougar. If the bear died so did the cougar without harming anyone but that doesn’t make for good press when you’re trying to sell tickets and make lots of money. Let’s face it: Hollywood for the most part is morally, ethically, creatively and mentally bankrupt when it comes to new ideas.

People want to be entertained and if it’s popular and people follow the leader, then it will make money. This is true of every decade. Look at all the anti nuclear insect/amphibian/piscean horror films of the 50s and 60s or all the martial arts films from the 60s and 70s.

No matter what media you’re in be it music, film, writing – soon as someone originates a genre or say a film that is successful, everyone else has to do it. Tarantino is a good example of present day imitation. Then there’s the Marvel Universe which after the last X-Men I just couldn’t watch anymore. The saturation level became ubiquitous to the point of nausea.

I asked a friend once why he had 160 cubic feet of milk crates filled with obscure albums no one had ever heard of and which he rarely if ever listened to. It’s a collection and it’s a social talking point. It’s sort of like Jethro Tull or Pink Floyd; after Aqualung and Wish You Were Here there just didn’t seem to be any point to listening to them anymore. Thank goodness no one could duplicate Steely Dan. LOL!

There are many imitators but only one original. I’ve never fully quite followed trends. I listen to what I want to watch or lissten to and what I think is good. I’m not and will never watch such schlock as Cocaine Bear. LOL Then again so long as the money keeps rolling in the studios and other media facilitators will keep churning it out.

Happy Trails