In the portfolio of a company’s offerings, there are no crown jewels more prized than the franchise. The roots of serial storytelling stretch all the way back to oral tradition, but the birth of publishing built on that tradition of long-term narratives and allowed them to flourish. That leads to two questions: what was the first completely American novel sequence to capture the attention of the young U.S., and how does it connect to, you guessed it, The Saturday Evening Post?

Many literary historians agree that the first real novel sequence was the French work Artamène ou le Grand Cyrus (usually called Artamène or Cyrus the Great in English). The first volume was published by Georges de Scudéry in 1649, though his sister Madeleine was the actual author, or at the very least, a significant co-author. The siblings put out ten volumes of the story, which cast contemporary people in roles associated with stories from myth and religion. At over 13,000 pages and nearly two million words, it remains one of the longest works of its type ever published.

Moving on a couple of centuries, we find James Fenimore Cooper. Born in New Jersey just days after the end of the Revolutionary War, he started at Yale when he was thirteen, but was kicked out for a pranks like locking a donkey in a classroom and destroying the door to a fellow student’s room. However, Cooper turned his youthful ways around and became an officer in the United States Navy. In 1811, he married Susan Augusta DeLancey.

The marriage would have a profound impact on Cooper’s direction in life, as a couple’s activity led to a major career change. While reading a novel aloud to his wife (as family reading was a common diversion at that time), Cooper realized that he had his own interest in storytelling. That revelation led to the writing of his first book, Precaution. The book was issued anonymously in 1820 and was well-received in both England and the U.S. His next book, 1821’s The Spy, turned out to be a major success, establishing him as the first American bestselling author; based on stories told him by his neighbor (and United States Founding Father) John Jay, Cooper’s The Spy combined two things that would be at the forefront of his most successful works: historical settings and action.

Cooper’s third novel would mark the beginning of a landmark series. 1823’s The Pioneers introduced readers to Nathaniel “Natty” Bumppo, also known by such names as Leatherstocking and Hawkeye, and his close Mohican friend, Chingachgook (who sometimes uses the name John Monegan). First appearing on the page as old men, Bumppo and Chingachgook have rich histories as scouts who help the settlers in the area. Cooper may have based Bumppo on the exploits of frontiersman Daniel Boone, who was already an American folk hero.

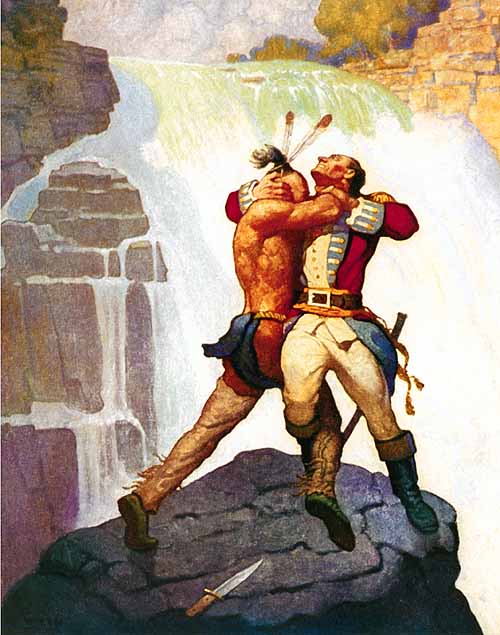

Though he would continue to write a diverse array of material including nonfiction history, Cooper returned to Bumppo and Chingachgook four more times between 1826 and 1841. The novels did not arrive in chronological order; rather, they skipped up and down the timeline of Bumppo’s life. While The Prairie, The Deerslayer, and The Pathfinder would all find popular success, it was the second book (both in terms of release and in the series continuity), 1826’s The Last of the Mohicans, that would prove to be Cooper’s most popular and enduring work.

The Last of the Mohicans took place around 1757 during the French and Indian War, which is the name typically associated with the battles of the Seven Years War between England and France that occurred in North America. During the conflict, both countries enlisted Native American tribes as allies to support the troops that each had landed on the continent. Settlers along the frontier who had arrived from England or were descended from earlier settlers frequently fought in England’s colonial militias. It is against this backdrop, and the historically accurate siege of Britain’s Fort William Henry by the French, that Cooper set his novel.

The Last of the Mohicans (1992) trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by TrailersPlaygroundHD)

The main events of the plot concern Hawkeye, Chingachgook, and Chingachook’s adult son Uncas guiding and protecting Cora and Alice Munro, the daughters of British Colonel Munro. British Major Duncan Heyward and singing master David Gamut are also part of their party, who frequently come in conflict with the Huron chief Magua, a secret ally of the French. The wilderness adventure aspect of the tale, combined with historical events, made the book extremely popular. Magua was one of the early, effective villains of American literature, and the story cemented the three central companions as significant heroes to the audience. Since 1909, there have been at least 10 American film adaptations of the work, as well as versions made for radio, television, comics, and opera; such is the story’s reach that it’s also been adapted for film in Europe several times, once as a German silent version in 1920 that featured Bela Lugosi (yes, you read that right) as Chingachgook.

Apart from his extremely popular Leatherstocking series, Cooper’s output was very diverse. He often infused his stories with social and political commentary, whether he was writing about maritime adventure or history. As an admirer of Thomas Jefferson, and a writer who wove that admiration into his work, Cooper often came under attack from political opponents in the Whig party. Cooper regularly sued his attackers for libel and won, which only created more enemies. The author more or less shrugged his shoulders and soldiered on. In additional to his novels, he published an array of short fiction, some of which ran in The Saturday Evening Post (including “Life Before the Mast,” which appeared in The Saturday Evening Post in 1843; you can read that story below).

When Cooper died in 1851, a number of famous fellow writers took it upon themselves to make sure that he was remembered for his expansive work. Everyone from Henry David Thoreau to D.H. Lawrence praised him, and Washington Irving spoke at one of his memorials. Over time, most of his works have faded from popular awareness, but the Leatherstocking Tales, particularly The Last of the Mohicans, carved out a seemingly immortal space. Cooper proved that a wholly American series of fiction could find popular success not only in his home country, but around the world. It’s appropriate that he wrote about guides and pioneers, because he opened a whole new frontier for American writers to explore.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now