What do the Stanford Cardinal, University of Massachusetts Minutemen, Dartmouth Big Green, Los Angeles Clippers, Syracuse Orange, Edmonton Elks, Cleveland Guardians, and Washington Commanders share? They’re all collegiate and professional sports teams that replaced their Native American mascots and nicknames (respectively the Indians, Redmen, Indians, Braves, Warriors, Eskimos, Indians, and Redskins).

In the past decade, the states of Colorado, Maine, and Minnesota have banned such mascots for their public schools. Similar legislation is under consideration in several states, including Massachusetts, where I teach high school social studies. While some continue to argue that Native American mascots honor the people who lived here earlier (and, of course, continue to live here; between 1-3 percent of the American population identifies wholly or in part as Native American), most agree that Native American mascots and other symbols misappropriate Native American culture and send harmful messages to students and young people.

While many “Indian” names remain, particularly at the high school level, the process of removing Native American mascots will continue. But once removed, will our only connection to our Native American past remain a few place names? While Indian mascots are highly problematic, they at least provided a passive awareness of the Native American presence, particularly in New England. In rightly leaving behind Indians as mascots, what do we lose? What could we gain?

I graduated from Saugus (Massachusetts) High School in the early 1990s. Our mascot was (and remains) the Sachem. In the Eastern Algonquian languages, a sachem is a paramount leader of several groups or villages, above a sagamore, which is more of a local leader. But we did not know that. Our sports jerseys and class sweatshirts had the word “Sachems” or Plains Indian heads emblazoned on the front. The cheerleaders at football games wore Indian “squaw” dresses with headbands, feathers, and face paint. We had been Sachems since youth leagues and thought nothing of it. We knew that Sachems had something to do with Indians and Saugus’s past, but not much more. A sharp disconnect existed between our mascot and the people who had lived here prior to European settlement.

The town of Saugus resides ten miles northeast of Boston on Massachusetts’s North Shore. Saugus is an Eastern Algonquian term, most likely meaning “wet or overflown grass land.” And it is, as the Saugus River flows through several miles of briny grasslands and marsh before entering the ocean at Broad Sound.

Many of the place names that we use here in Massachusetts and New England are Eastern Algonquian terms. Nearly all are functional descriptions of the landscape, such as Massachusetts itself, “at the great hill,” which refers to Great Blue Hill in Milton. Those Eastern Algonquian terms for places like Saugus and Massachusetts became embedded into settler society in the first generations of cohabitation, as Native Americans used these terms to describe to the English what to look for when they traveled. But after 400 years, those place names have become Americanized, their origins severed.

In 2015 I started teaching at neighboring Winchester High School, which also used the Sachem as their mascot. I saw in my students the same disconnect between the Sachem mascot and the Native American origins of their home town.

When I inquired about changing the mascot, I learned that it would be the decision of the town, and not the high school, as the Sachem had become one of the town’s traditions. We would face great opposition if we tried to change it.

I suggested building some sort of museum exhibit, to better explain the Native history of the region to students. School leaders were supportive, and I started to develop my knowledge of the Pawtucket peoples, the Native American group that had controlled northeastern Massachusetts prior to European settlement.

In the late 2010s more opposition grew in Winchester to the use of the Sachem as a mascot; 2020 pushed it over the top. In June, in the weeks following the murder of George Floyd and the early months of social distancing, the School Committee voted to remove the mascot. A committee of students, faculty, administrators, and community members met and produced a new mascot in early 2021 – the “Red and Black,” the colors of the former mascot.

After conducting further research with students, the exhibit opened earlier this year. It has three components: a physical exhibit over six display-case shelves at the main community entrance to the high school’s gymnasium; a slideshow that plays within the display case; and a digital exhibit, accessed via a QR code. The exhibit has three sections, presenting the Pawtuckets, Indians as mascots, and the Winchester High School Sachem.

So, how did we end up with Indian mascots like the Sachem in the first place?

Indians as Mascots

Organized amateur sports began in this country in the early to mid-nineteenth century, with professional sports arising in the decades following the Civil War. Baseball became the first professional team sport, with college (amateur) football gaining popularity from the 1880s. Teams needed ways to differentiate themselves from one another, and a name attached to the team outside of location formed one way. That name or nickname became connected to a mascot, a “lucky charm” for the players, which is the word’s origin, from the French la mascotte. Now (and then), to ensure that our team has good luck and wins the game, the mascot should scare the opponent. Therefore, many mascots are fierce creatures like lions, tigers, and bears.

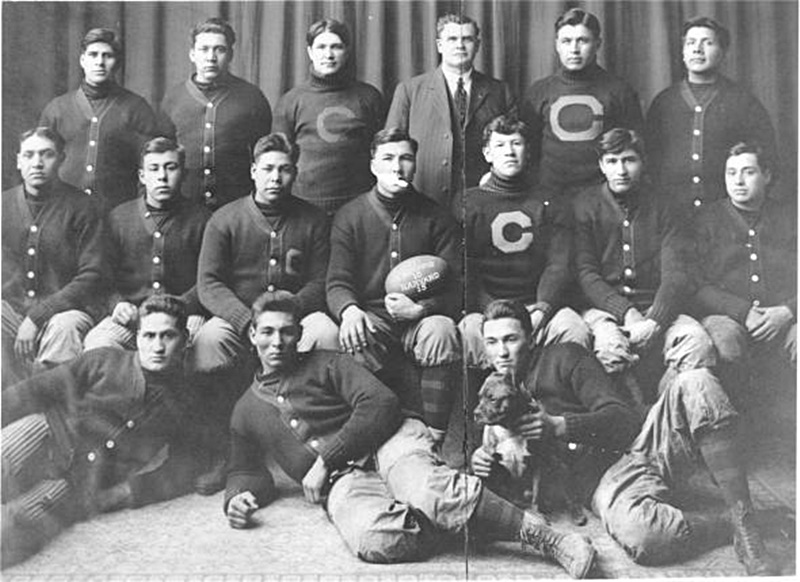

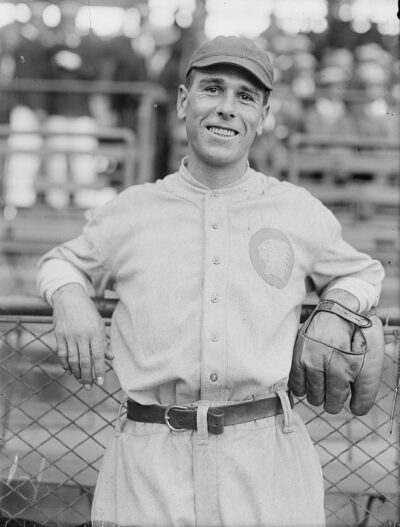

Widespread use of Indians or Indian-related terms as mascots only came in the early twentieth century through two means. First, the exploits of Jim Thorpe and the Carlisle Indians, college football’s first powerhouse, popularized the use of Indians as mascots. Thorpe, arguably the top American athlete of the twentieth century, a member the Sac and Fox tribe, went to the Carlisle (Pennsylvania) Indian Industrial School, the most well-known of the Indian boarding schools. Those repressive institutions, required for most Native American youths, attempted to erase Indian culture from the students and make them American. Converting tribal martial routines into American sports formed one way. Thorpe played football at Carlisle for coach Glenn “Pop” Warner, who innovated backfield formations and the forward pass, taking advantage of his players’ speed and skill. The high point of Thorpe’s Carlisle years was 1911 and 1912. Following Carlisle’s 18-15 victory over Harvard in November 1911, the Boston Globe declared in an above-the-fold headline: “Indians Win in Stadium.” The following year the team defeated West Point and its starting running back, Dwight Eisenhower. The Indians went 11-1 and 12-1-1 in those seasons. In-between, Thorpe won gold medals in the decathlon and pentathlon at the Stockholm Olympics. (He later played professional baseball and football and served as the NFL’s first commissioner.) Because Carlisle kept defeating the top collegiate teams in the country, its “Indians” became something to be feared and emulated. Therefore, other teams wanted to scare their opponents by playing as “wild” and “fierce” as the Carlisle Indians. (Carlisle stopped playing college football after the 1917 season.)

Second was the Boston Braves baseball team. James Gaffney, a construction company owner from New York, bought the National League Boston Rustlers in late 1911. Prior to the 1912 season he renamed them the Braves, an homage to New York City’s Tammany Hall, of which he was a member. Tammany Hall had long had an Indian as its mascot, and Gaffney hoped to continue receiving construction contracts from the other members of the political organization. (Thorpe and the Carlisle Indians were dominating the competition at this exact time.) The Boston Braves appear to be the first professional team to maintain a Native American mascot.

The Boston National League team had long finished near the bottom of its league, never making the World Series. In 1914, two years after Gaffney’s purchase, the Braves improbably went from worst to first and won the World Series. (The team later moved to Milwaukee, then Atlanta.) The following year the Cleveland Napoleons changed their name to the Indians, in part inspired by the Braves’ success. And two decades later, when Boston received a team in the expanding National Football League, it was named the Braves, as the team played at Braves Field. The following year in 1933 the team moved to Fenway Park and changed its name to the Redskins, as the owner did not want to pay for new uniforms. The Redskins left for Washington a few years later and, in 2022, after years of protest, changed their name to the Commanders.

For most Americans in the early twentieth century, Native Americans shifted from a reality to a historical fiction. On their reservations and not openly seen, Indians matched well with lions, tigers, and bears as mascots. They were another fierce creature. Other teams, at professional and amateur levels, began to use Native terms for mascots and team names in the following decades, including Winchester High School, just miles away from the Boston Braves and Redskins.

Winchester High School Sachems

If the first three decades of the twentieth century saw the solidification of professional and collegiate sports, high school sports became prevalent in the following decades. By the 1940s and 1950s, most Massachusetts high schools had a mascot. But what to choose?

The town of Winchester had been the final home of the Squa Sachem of Mistick – her title, as we do not know her name – the widow of Nanepashemet, the great sachem of the Pawtucket people of northeastern Massachusetts. The Pawtuckets died in great numbers in the still-undetermined 1610s epidemic and the 1633 smallpox epidemic. For societies that depended upon oral transmissions of the past, these epidemics not only killed up to 90 percent of coastal Massachusetts’s Native American population by the mid-1630s but also their (and our) historians. No group claims the Pawtucket name or heritage today. (The federally-unrecognized Massachusett tribe claims northeastern Massachusetts as their heritage lands, which we should support, as the Squa Sachem was herself a Massachusett, whose territory bordered the Pawtuckets to the south.) In 1934 a New Deal work-relief program installed a mural at the Winchester Public Library that depicts the 1639 transaction between the Squa Sachem and Massachusetts Governor John Winthrop, of “selling” land for wampum, coats, and maize. (To the Library’s credit, it historicizes the problematic portions of the mural.)

While Winchester High School used Native American images and symbols since the 1920s, and some youth and adult sports teams in town were occasionally called “Indians” in the press in the 1920s and 30s, the high school only settled on the “Sachem” as its mascot in the late 1950s. The mascot went through several representations of the Sachem mascot over the years. None accurately represented the Pawtucket peoples and rather depicted stereotypical caricatures of Plains Indians with headdresses, war paint, feathers, tomahawks, and peace pipes. Students would occasionally dress up as Indians at sporting and other school and town events, and most uniforms would contain either the word “Sachems” or a depiction of an Indian. From the late 1950s, the Sachem appeared as a standing man, wrapped in a blanket, with a single feather in a headband. In 1977 a high school student designed a new logo for the Sachem, a more abstract representation of a face in profile. Youth sports teams in Winchester used the Sachem name and logos as well.

Opposition to the Sachem first developed in the late 1990s, prompted by an alumnus of Native American heritage who returned to coach. The town put the mascot to a vote in 2000, overwhelmingly choosing to retain it. Grass-roots support to change the mascot slowly built in the community over the next two decades, with the School Committee voting to remove the Sachem in spring 2020.

Three years in, the replacement “Red and Black” does not appear to be the best choice. Whether for financial reasons or because the new mascot is simply two colors rather than a new symbol like an animal to build around, most Winchester youth sports leagues continue to use the Sachem and Indian symbols. (We’ll see if that lessens over time.) For students the disconnect remains between this mascot and the local Native American past and present. Hopefully the exhibit can start to change that.

Conversations

How do we build stronger Native American connections to our everyday lives outside of place names and mascots? Many who defend the continued use of Indian-related mascots say that they honor the former (and current) Native American residents of this region. Honor is not the right concept. Societies honor those who have passed. Thereby saying that we honor Native Americans by using Native-themed mascots such as the Sachem, we cement them into the past.

Rather than honor the Pawtucket people, a better concept may be a conversation, a dialogue with their worldview and the way they lived their lives and treated this land. When we have a conversation, we can speak with their progeny today, the Native Americans of this region and other places. We can speak with historians, who hold a more nuanced view of the past. And we can speak with ourselves as a community.

The Pawtuckets, Massachusett, Nipmucs, Wampanoags, and other Eastern Algonquian-speakers shaped the landscape of eastern Massachusetts and New England to their advantage and beliefs. By conversing with Pawtuckets we can continue and at times reinstitute Native terms for places, while making residents aware of their locative meanings. By conversing with Pawtuckets we can recognize and place explanatory markers at significant Native American places, knowing why and how they used those locations. By conversing with Pawtuckets we expose ourselves to other ways to treat and interact with our environment and the natural world. And by conversing with Pawtuckets we can deliver to young people today another path, another way to bring value to their lives, whether through this exhibit or classroom lessons that incorporate local Native heritage and how they physically shaped their world, such as Saugus High School does in their ninth-grade social studies classes.

Both Winchester and Saugus built new high schools in the last decade. Winchester placed its Sachem mascot on the new building as a large decal on the glass window at the entrance, knowing that it could be easily removed if the town changed the mascot. It was. Saugus had its Sachem mascot – a Plains Indian leader in a headdress – built into the side of the building, four stories tall, overlooking Route 1, a heavily-travelled three-lane highway. There’s no easy way to take that off. And it sends an unmistakable message.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

magic was a predictive spelling mistake. Supposed to be. MAJOR

Woke culture has gone too far. There is not a damn thing wrong or disrespectful with a team having the “Indians” name. I am a part Cherokee and never took any offense to my rural high school in TN being the “Indians” or in the case of female sports “Indianettes or Lady Indians.” What the hell is wrong with people? For me personally, Cleveland will always be the “Indians” and Washington will always be the “Redskins.” I am so glad that my high school has not become a victim of the woke culture. Being woke is not a good thing and the culture needs to be stopped.

I do not believe that the Cleveland Indians mascot/logo in any way denigrated the Native American people. It was merely a fun logo, a caricature for sure but NOT a harmful one except in the minds of some people ( native or other) who may have a magic self esteem issue and want to find something to blame for their perceived woes. Sad