This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

As the 2024 presidential campaign moves into its final six weeks, anti-immigrant rhetoric has become a particularly prominent feature. Donald Trump has relied on such rhetoric since he launched his first campaign in 2015. But in recent weeks he and his running mate J.D. Vance have significantly ramped up their anti-immigrant stance, with a focus — as illustrated by Trump’s reference to it during the recent presidential debate — on thoroughly debunked stories of Haitian Americans in an Ohio town “eating the dogs” and “eating the cats.”

Stories of immigrants eating disgusting or dangerous foods have been part of xenophobic narratives for centuries, and have remained quite similar across many different time periods and communities (cats have been in particularly frequent danger). That’s just one of a number of strikingly consistent myths that have cropped up again and again among those advancing these anti-immigrant narratives. Here I’ll take a look at a few examples of those fabrications, along with alternative perspectives that reveal how consistently wrong those myths have been.

One of the most common anti-immigrant myths has been that these arrivals are seeking to remake the entire United States in the image of their own culture, one explicitly defined in this perspective as lesser than that of the U.S. In 1755, Ben Franklin made that case against German immigrants to his adopted home of Pennsylvania, wondering, “Why should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a Colony of Aliens, who will shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us instead of our Anglifying them, and will never adopt our Language or Customs, any more than they can acquire our Complexion.” Franklin went even further with his attacks, characterizing these German immigrants as “generally of the most ignorant Stupid Sort of their own Nation,” and worrying that these lesser arrivals would “soon outnumber us.”

By his final years of life in the immediate aftermath of the American Revolution, however, Franklin had not only realized that he was entirely mistaken about that German American community in Pennsylvania, but was also involved in steps to help them become even more fully supported within that new state. In 1787, just three years before he passed away, Franklin was serving as President of the Council of Pennsylvania and was instrumental in the Assembly’s chartering of a new college in Lancaster, one focused on educating German Americans and dedicated “to promoting an accurate knowledge of the German and English languages,” making it the first bilingual college in the nation. Franklin also gave 200 pounds to the institution, twice as much as any other initial donor, and it was named Franklin College in his honor.

A century later, Chinese Americans had become a central target for anti-immigrant attacks. One of the most prominent purveyors of those narratives was Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan, who is widely known for his courageous dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) but who in that same dissent called the Chinese “a race so different from our own that we do not permit those belonging to it to become citizens of the United States.” Two years later, Harlan would deliver a public lecture that went even further, arguing that “this is a race utterly foreign to us and never will assimilate with us.” Another of the most consistent anti-immigrant myths is that these arrivals are too distinct from “Americans” (however that ambiguous community is defined in each instance) and will never be able to be part of this community.

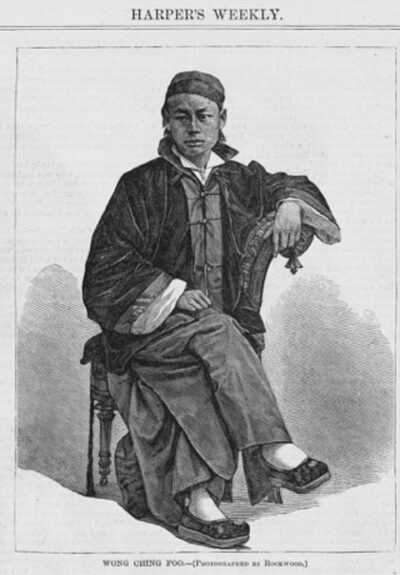

Yet a famous Chinese American contemporary of Harlan’s made precisely the opposite case, arguing for an authentic and multilayered Chinese American identity and using legal and political means to fight for that community’s equal standing in the U.S. The journalist and activist Wong Chin Foo (1847-1898), who was born in China but naturalized as a U.S. citizen in the 1870s, published an 1887 column — in The Chinese American newspaper he had founded four years earlier — entitled “Why Am I a Heathen?,” arguing for traditional Chinese religious beliefs as part of his American identity. And at the same time he fought to extend American democracy and rights to the Chinese American community, including his 1884 founding of the nation’s first association of Chinese voters and his role in the 1892 creation of the Chinese Equal Rights League.

Anti-immigrant myths haven’t just portrayed these communities as outside of and different from those in the United States, however. They have also consistently depicted immigrants as threats to the nation and their fellow Americans (the “real Americans” in this narrative). In the first few decades of the 20th century, with the U.S. occupying the Philippines after the Spanish American War, Filipino immigrants to America became a focus for these xenophobic fears of threatening arrivals. In one telling 1936 court case featuring a Filipino young man over whom two white girls had fought, San Francisco Municipal Court Judge Sylvain Lazarus ruled “This is a deplorable situation…It is a dreadful thing when these Filipinos, scarcely more than savages, come to work for practically nothing, and obtain the society of these girls.” Such sentiments led to the creation of laws like the 1935 Filipino Repatriation Act, which sought to return hundreds of thousands of Filipino Americans to the Philippines.

Yet over these same decades, Filipino Americans contributed heroically to the U.S., fighting for their fellow Americans on a number of fronts. They did so through military service, as illustrated by West Point graduate and WWI and WWII hero Vicente Lim. They did so through community organizing and activism, as realized by labor leader Pablo Manlapit. And they did so in a particularly striking way during the 1918-20 Influenza Epidemic, as U.S. Navy veteran Agripino Jaucian, his nurse wife Florence, and the members of the Filipino Association of Philadelphia Inc. (FAAPI) that the couple had founded a few years later provided free medical supplies and treatment to Philadelphia residents affected by that deadly pandemic.

Far from recognizing such heroic contributions, xenophobic narratives have consistently sought to define immigrants as criminals, even going so far as to characterize their very presence in the United States as a criminal violation. That’s particularly ironic when it comes to arrivals who are seeking asylum in the U.S., and even more ironic still when they do so due to unstable or dangerous conditions in their home nation that the U.S. helped create. There’s no immigrant community of whom that’s more true than Haitian Americans, whose nation has seen a century of U.S. invasions, occupations, and interference and yet who have found themselves time and again denied asylum, treated as dangerous criminals for the very act of coming to America.

In an even more ironic twist, the U.S. Attorney who will be prosecuting accused presidential assassin Ryan Routh is Markenzy Lapointe, a groundbreaking legal advocate throughout his inspiring career — and the first Haitian-born U.S. Attorney.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Please do inform the public to look closely at me and my work, js. They can start with my new podcast:

https://americanstudier.podbean.com/

or the most recent of my six books:

https://rowman.com/ISBN/9781538143421/Of-Thee-I-Sing-The-Contested-History-of-American-Patriotism

or any of the other work linked here:

https://linktr.ee/americanstudier

I look forward to their thoughts!

Ben

This is a wonderfully well-written article.

It’s not just Mexico; there are intolerable living conditions in other countries such as Haiti, Venezuela, and Honduras. These conditions have also contributed to the record-high increase in border crossings. I would suggest that readers and skeptics of immigration research the voyage of the MS St. Louis**, where in 1939, 937 Jewish passengers seeking asylum** were turned away by the U.S. when it reached its shores. The ship was forced to turn back to Europe. Some European countries, including the United Kingdom, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, accepted passengers. However, after Hitler’s invasion of these countries, 254 of the passengers who remained in mainland Europe perished in concentration camps.

This is the heart-wrenching reality of what happens when you turn away refugees, immigrants, and people seeking asylum. What’s even more heartbreaking is that there are people who simply don’t care about the fate of these individuals. They didn’t care when Jews were starved and burned alive in ovens, and today they don’t care that Central Americans are starving, many suffering from malaria and tuberculosis. Due to extreme poverty, there is also a high level of human trafficking occurring. And still, they don’t care! Their attitude? “Turn your ship around! It’s not our problem!”

A **”zero tolerance”** policy will not work. It defies immigration laws; it doesn’t support them. There are too many factors and variables to consider—one being asylum seekers. Under a zero-tolerance policy, you’re immediately prosecuted if you cross illegally, even if you are seeking asylum. A person might not have all their paperwork in order before crossing the border if they’re running for their life.