This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

As I begin drafting this column in the early morning hours while my sons sleep, planning to continue working on it here and there amidst a day of homeschooling and transitioning all my classes online and failing to stay away from social media and the news, it’s fair to say that Covid-19 is the inescapable lens through which all of us are currently viewing our world. As a result, one central subject for historians and public scholars has been the 1918-1920 influenza pandemic, one of the prior historical moments that most closely parallels this unfolding global crisis.

As always, no history can or will exactly line up with our current situation, which is unprecedented in various and often frightening ways. Yet if history doesn’t repeat itself, it most definitely rhymes (as Mark Twain is alleged to have said). And if we examine that 1918-1920 moment in American society and culture, I believe we can find a number of striking lessons for 2020. I’ll highlight two warnings and one inspiration we can take away from this century-old pandemic and its American contexts.

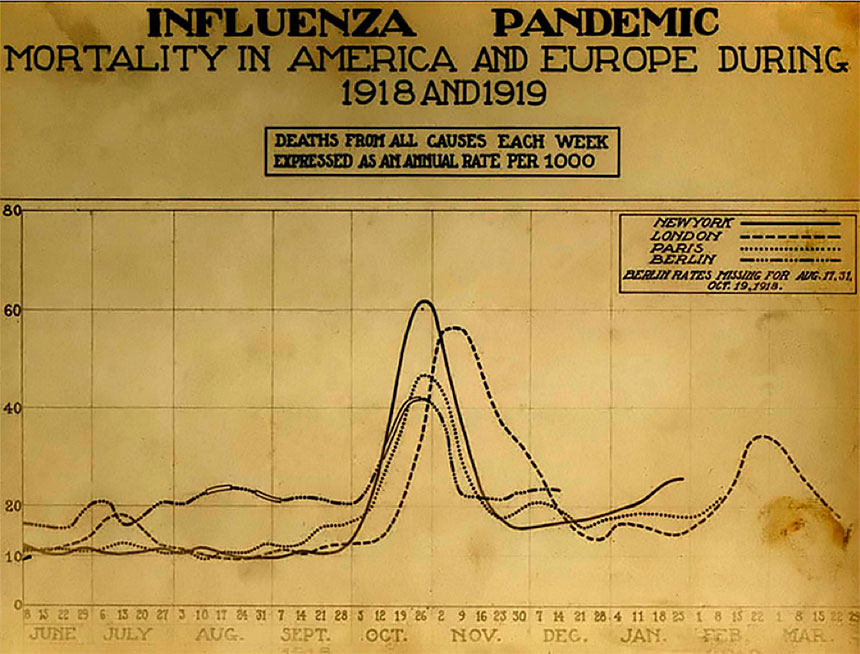

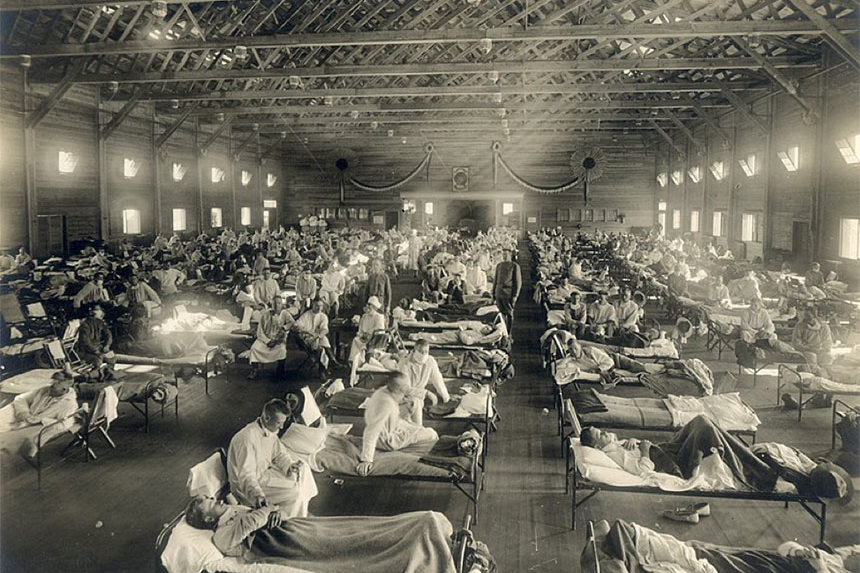

Perhaps the most striking lesson and warning emerges from a community and government’s abject failure to practice social distancing (not yet known as such, of course) and its dire consequences when it comes to the containment of a virus. The influenza epidemic first emerged in March 1918 among U.S. army recruits in Kansas’s Camp Funston, and then traveled with them across the Atlantic to the trenches of World War I. By the summer of 1918 hundreds of thousands of soldiers from every involved nation had become ill, and the pandemic soon spread to civilian populations throughout Europe and began threatening to do the same in America.

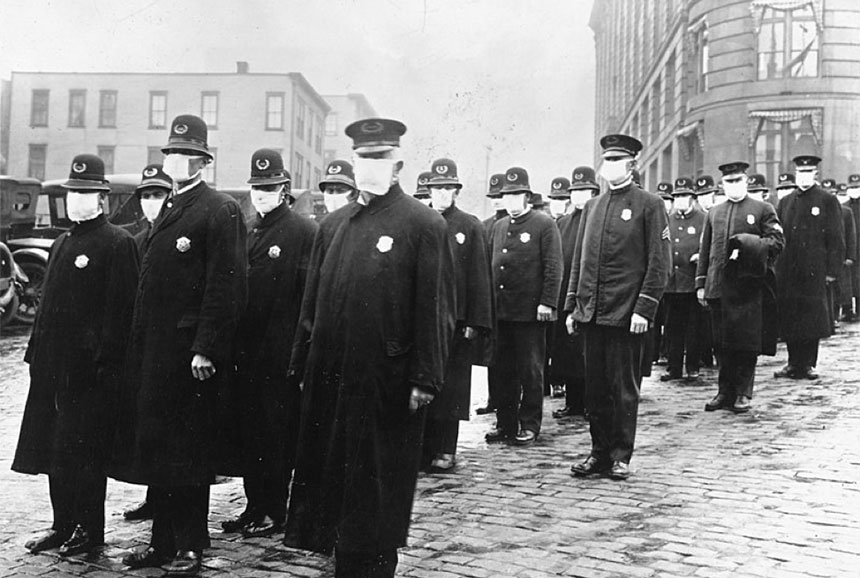

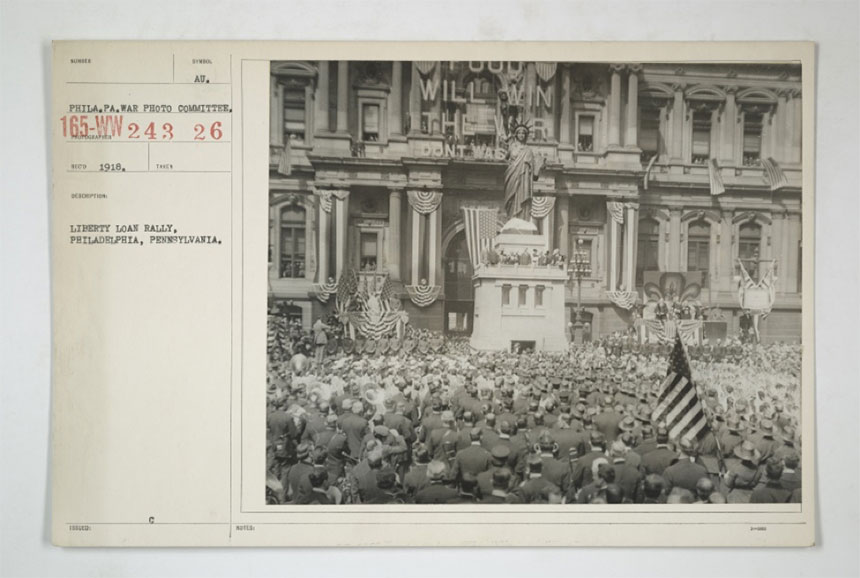

In response, many American communities sought to minimize large gatherings and public events. In September 1918, for example, monthly draft call-ups for military reinforcements were canceled due to new outbreaks in many army camps. But Philadelphia had a planned parade on September 28th, to raise money for war bonds and otherwise cheer on the war effort, and its director of public health, political appointee Wilmer Krusen, scoffed at suggestions that the parade should be canceled. What was happening in military camps was just “old-fashioned influenza or grip,” he argued. As long as people avoided coughing or sneezing in public, they’d be fine. The parade went off as planned, with more than 200,000 Philadelphians crowding in to watch.

The results were truly catastrophic. To quote historian Kenneth Davis, “Within 72 hours of the parade, every bed in Philadelphia’s 31 hospitals was filled. In the week ending October 5, some 2,600 people in Philadelphia had died from the flu or its complications. A week later, that number rose to more than 4,500.” Even at that point, the Philadelphia Inquirer was pretending things were okay, complaining in an October 5th editorial, “Talk of cheerful things instead of disease. The authorities seem to be going daft. What are they trying to do, scare everybody to death?” But this one ill-advised event fundamentally changed the course of the disease, not just in Philadelphia (where nearly 12,000 eventually died) but throughout the United States, reflecting the vital need to avoid large gatherings or crowded places, practice social distancing, and not in any way minimize a pandemic’s threat.

As the influenza pandemic continued to spread, it was often dubbed by a new name, the “Spanish Flu.” The reason behind that appellation was contextual and complicated: many nations, especially those directly involved in World War I, had long sought to minimize the pandemic’s presence and threat, at least in part so as not to reveal their armies’ weakness; whereas Spain, neutral in the war, had admitted the flu’s devastating realities far earlier and more fully. Yet whatever the specific origins of this name, it quickly became a central frame through which the pandemic was defined, linking this global disease to a particular nation in limiting and discriminatory ways. That is, even though it seems clear that the pandemic originated in U.S. military camps in Kansas, it instead became and has remained fundamentally linked to Spain.

The story and effects of this informal but influential name offers a second lesson and warning for 2020. In recent days, President Trump and many of his supporters have begun calling Covid-19 the “Chinese virus,” often using the Spanish flu as part of an overarching argument for designating pandemics by their places of origin. The inaccuracy of that history when it comes to the 1918 pandemic should give those who make such arguments pause. But the broader and more crucial point is that linking a global pandemic to a particular nation or community itself represents both a minimizing of and a distraction from the profoundly serious and truly shared nature of such threats. A global virus doesn’t care at all about nations, nor can attempting to lay blame for its origins help respond to, contain, and treat such a pandemic. Indeed, all that such names can do is create divisions and fears that will make conducting coordinated, collective, national, and global responses more difficult.

As we move more fully into such global responses to Covid-19, we can take one final, far more inspiring lesson away from the Influenza Pandemic. This one is likewise set in Philadelphia, where a Filipino-American community organization modeled collective action and spirit in the face of the disease’s horrific effects. In 1912, Filipino immigrant and retired U.S. Navy man Agripino M. Jaucian organized 200 fellow Filipino-American naval veterans into the Filipino Association of Philadelphia, Inc. (FAAPI). Jaucian had experienced the era’s developing anti-Filipino racism, and believed that such a communal association could both offer solidarity for members of the community and help them become a more thriving part of American society. After a few years of meeting informally in Jaucian’s home, in 1917 FAAPI drafted a constitution and applied successfully for incorporation.

The following year, as the influenza pandemic unfolded in their home city, the organization performed some of its most significant and heroic work. Agripino’s wife Florence was a registered nurse at nearby Wilkes-Barre General Hospital; working in coordination with her and her contacts, FAAPI provided free medical supplies and treatment to Philadelphia residents fighting the disease and its effects. As I highlight in my book We the People: The 500-Year Battle over Who is American (2019), this moment echoed and extended the legacy of service and sacrifice from Filipino-American communities since at least the War of 1812. And it embodied precisely the kind of collective, communal effort that both defines America at its best and will be vital if we, in this nation and around the world, are to fight this 21st century global pandemic.

May we all learn from the past, share such solidarity in the present, and offer our own inspiring lessons for the future when it looks back at the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020.

Featured image: Camp Funston at Fort Riley, Kansas, during the 1918 Flu Pandemic (U.S. Army)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thanks for the comment, Jacob. I think a thoughtful, in-depth analysis of COVID-19’s origins, and of how China’s actions contributed to its early stages and effects, is certainly important–just as an analysis of the early actions and/or inactions of every country and government has a great deal to tell us.

But I would argue that using shorthand phrases like “the Chinese virus” isn’t thoughtful or analytical, but rather precisely an attempt to short-circuit analysis (often, in the case of US leaders, of our own actions and choices) by pandering to emotional reactions and stereotypes.

Thanks,

Ben

Since the origin of the pandemic from 100 years ago was incorrectly ascribed to Spain, it is therefore morally wrong to indicate where any pandemic since then came from, even when it is known with certainty where it came from? Even when the specific actions of that country played a large part of its spread? A great example of a non-sequitur.

It is significant that the virus originated in communist China as the lack of a free press, and ultimately the totalitarian government there, prevented full disclosure of what was going on. Leading other nations not to prepare for it.

What a wonderful article you’ve composed here comparing the 1918-‘20 pandemic with the current one.

American history has an unfortunate bad habit of not giving credit to remarkable Americans, be they a female architect, or a male architect of the civil rights movement, both for unfair reasons per articles right here, this month.

Here, we learn some new untruths regarding the origins of the 100 year old pandemic, but also the contributions of Filipino Agripino Jauciain and his (nurse) wife, Florence in fighting the disease at that time.

Hopefully, somehow, the President will get on the right track across the board in both words and deeds, and not have both seen subsequently as contradictions of one another.

We need cooperation of both political parties (broken as both are) on the 2 trillion stimulus package he wants to put through. Without it, we’ll be seeing a lot more deaths; and not from the Covid-19 pandemic.