Across two decades and treaties, the lands of the Dakota were dwindling. Dakota woman Ellen Simmons watched the world change around her as she gave birth to her daughter, Gertrude, on a cold February day in 1876, safe within their community along the shores of the Missouri River in Dakota Territory. Miles away from their door, conflict raged between the United States Army and the Indigenous people of the plains. That summer, as Ellen cradled her young daughter, an alliance of Indigenous warriors defeated Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer’s Seventh Cavalry at Little Bighorn Creek in Montana. The United States government would not let a loss happen again.

As the reservation system pinned Indigenous Americans in their places, another system developed alongside: a network of boarding schools that would educate Indigenous children far from the homes they knew and the families who loved them. Some children went because officials frightened their parents with claims of what would happen if their children did not go. Other children, like Gertrude Simmons, went by choice, excited to encounter a new world.

Missionaries came to Simmons’ home on the Yankton Reservation when she was eight. She was awed by their tales of big red apples and the chance to ride on a train, and curious about what lay beyond her home. Her mother was more skeptical, but agreed to let her daughter go east. Ellen Simmons said, “she will need an education when she is grown, for then there will be fewer real Dakotas.” Ellen also believed that this education, although it would take her daughter away from her, was part of a debt being repaid to the Dakota by white Americans.

Simmons became one of the thousands of Indigenous children sent to boarding schools funded by the United States government. The Native American boarding schools began in the late 1860s, with more than 400 schools operating across the nation for the next century. Some were operated by government officials, while others were run by religious institutions. Simmons attended the Quaker-run White’s Indiana Manual Labor Institute in Wabash, Indiana. An article published in 1888 noted that students came to the school for three years, and the U.S. government provided funding for each pupil. The goal was to teach Indigenous children how to be productive: “The Boys [are] Taught to be Blacksmiths, Carpenters and Farmers, and the Girls to be Cooks and Housekeepers.” It was an education designed to help Indigenous youth assimilate into white American culture.

Like other students at the school, Simmons’ hair was cut, and she was dressed in western-style clothes. She learned to read and write, and she learned to assimilate. When she returned home, Simmons found that her experiences set her apart. “I was neither a wee girl nor a tall one; neither a wild Indian nor a tame one,” she later wrote. She continued her education but grappled with this new sense of identity. Back in Indiana, Simmons enrolled in Earlham College, another Quaker institution, gaining a reputation as a violinist and orator.

In 1897, Simmons joined the teaching faculty at Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, one of the most well-known government boarding schools by that time. The school’s mission, according to its 1895 publicity pamphlet, was to “lead the Indians into the national life through associating them with that life, and teaching them English and giving a primary education and a knowledge of some common and practical industry and means of self-support among civilized people.”

Hiring Simmons was part of that mission: She was a young Native woman who had been educated in a similar school and excelled. As a teacher at Carlisle, administrators expected that Simmons would become a role model for the children there.

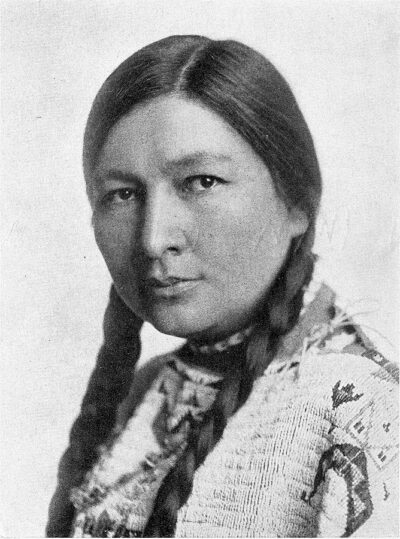

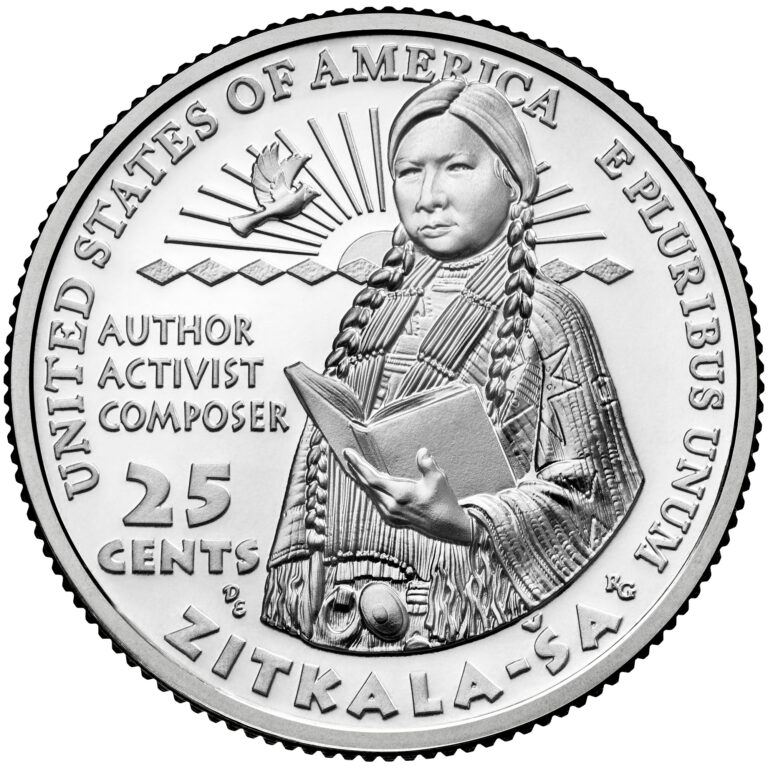

Simmons came to teach music, but she left just two years later, speaking out critically against the boarding school system and embracing her identity as an Indigenous woman with something to say. As a teacher, the Carlisle Indian School had sent her out West to bring back more Indigenous children to study there. Returning home, she saw how poorly her family and others on the Yankton reservation lived. The reality of life for Native Americans contrasted deeply against the vision of assimilated Native life taught at Carlisle. During her time at Carlisle, Simmons began writing and publishing under the name Zitkala-Ša, meaning “Red Bird” in Lakota. Zitkala-Ša’s works were published in The Atlantic Monthly and other venues, focusing on Native American stories and autobiographical accounts. Back with her mother in South Dakota, Simmons published her first volume of those works under the title Old Indian Legends, giving Zitkala-Ša as the author’s name.

In Le1902, she married a Dakota man named Raymond Bonnin, and the two moved to Utah to work with the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Over the next decade, Gertrude Simmons Bonnin continued to write under the name Zitkala-Ša, becoming the first Indigenous woman to write an opera. The Sun Dance Opera was a collaboration between her and a professor at Brigham Young University. It opened in 1913 with a cast that included both Indigenous and non-Indigenous performers.

Indigenous Americans did not have full citizenship when The Sun Dance Opera premiered. The Society of American Indians (SAI) was formed in 1911 to help Indigenous Americans hold on to their traditional ways of life while also fighting for citizenship. Zitkala-Ša became the national secretary for the SAI, and she and her husband moved to Washington, D.C. to do their work for the organization. While they later left the SAI, both remained committed to the cause of citizenship and full rights for Indigenous Americans.

Throughout the 1920s and until her death in 1938, Zitkala-Ša fought for Indigenous Americans’ rights. In 1924, the same year that the Indian Citizenship Act passed, she co-authored a report entitled “Oklahoma’s Poor Rich Indians: An Orgy of Graft and Exploitation of the Five Civilized Tribes – Legalized Robbery.” This investigation revealed the ways that the federal government was using its power to take money and property from Native Americans who owned lands where oil had been discovered. A century later, these issues, and a series of murders within the communities, have once again drawn attention through the book and film Killers of the Flower Moon. By 1926, Gertrude and Raymond Bonnin founded the National Council of American Indians to continue their work toward full suffrage for Indigenous Americans. This work would occupy the rest of her life; when she died in 1938 Zitkala-Ša was buried in Arlington Cemetery as the wife of a World War I veteran.

Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, or Zitkala-Ša, was educated to be a woman who would do what she was told. That, she was taught, was the way to be a productive member of society. Instead, she became part of a generation of Indigenous children who survived the boarding school system and actively worked to create a new future for their people — one that went beyond what the United States government and its representatives offered.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thank you for this in-depth article on a truly remarkable, multi-talented American woman. She definitely deserves to be one of the women featured on the U.S. Mint’s ‘American Women Quarters Program’. Also, Ms. Zitkala-Sa’s story and accomplishments should be in American history books moving forward. She’s an inspiration to us all.