This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

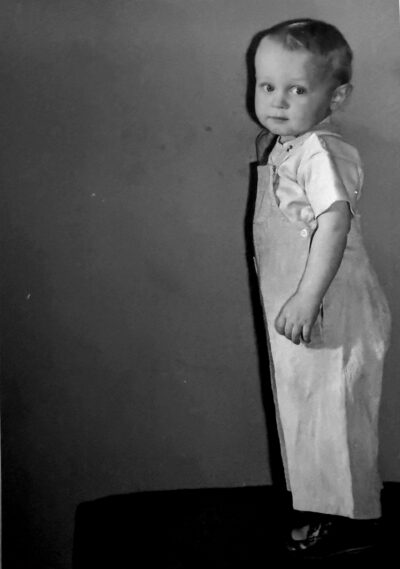

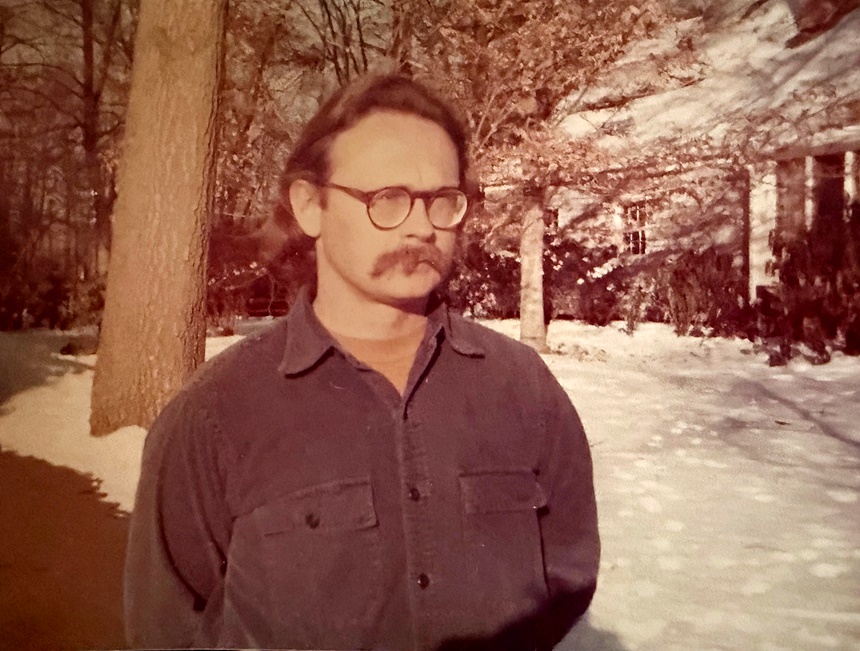

On the morning of Sunday, March 2nd, my father, Stephen Railton, passed away, surrounded by loved ones in the Charlottesville home where he and my mom had lived for 45 years. I said a great deal of what I’d want to say about his impressive and inspiring life in this obituary for the local paper, and a great deal of what I’d want to say about what he meant to my own life and work in this 2021 Considering History column in honor of my parents’ 51st wedding anniversary (they very nearly made it to their 55th!). He was an exemplary model for the most important role I’ll ever perform, being a Dad (as well as a wonderful grandfather to those two amazing young men), and I’ll miss him every day and be inspired by him even more often.

Here in this space, I wanted to pay tribute to my dad by highlighting the most consistent throughline of his life: educational communities. More exactly, at each stage of his life Steve Railton embodied the best of American education, reminding us of the crucial importance of such vital — and here in 2025 frustratingly endangered — goals as supporting student journalism and activism, listening to and amplifying student voices and perspectives, and connecting students (and all Americans) to our literature, culture, and history.

Throughout his own time as a student, first in the public schools in Haworth, New Jersey and then as an undergraduate and graduate student at Columbia University, Steve was a prolific and published writer. That included creative writing, such as the multiple plays he wrote and even had staged at Columbia. But it also meant student journalism, as he wrote columns and book reviews for both his high school paper and for Columbia’s student newspaper the Daily Spectator. Student publications are often one of the first targets of both budget cuts and crackdowns on free speech, not least because they represent a space in which students can question and challenge their own institution as well as broader powers-that-be, and Steve’s student publications reflect all that would be lost if such spaces were cut or silenced.

In one of his Daily Spectator columns, Steve wrote about a trip to Washington, D.C.’s National Mall to take part in late 1960s anti-war protests. While I’m sure that was a particularly striking experience, Steve didn’t need to travel anywhere to be part of inspiring activism, as Columbia itself was shut down by student protests for multiple spring semesters during his undergraduate years (1966-1970). For the rest of his life Steve would reflect on how he learned as much from — and grew as a result of — being around and a part of these protests as he did from any official educational experiences at Columbia, and he would carry forward a strong sense of how educational communities should be spaces for collective action, as a reflection and extension of their core mission.

After receiving his PhD in English from Columbia in 1974, Steve was hired as an assistant professor of English by the University of Virginia. He would remain there for the rest of his 45-year career, a lifelong commitment to this institution of public higher education that (as I complete my 20th year at Fitchburg State University, part of the public higher ed system in Massachusetts) I can only hope to parallel. And from his first semester in the fall of 1974 through his final classes in the spring of 2019, Steve placed his entire emphasis on teaching, on doing everything he could to listen to, support, and amplify the voices of his students (undergraduate and graduate alike). The moving testimonials from countless such students, during his career and even more so in the weeks since his passing, has reflected just how influential that work was, how many young lives he impacted for the better, inside and far beyond the classroom.

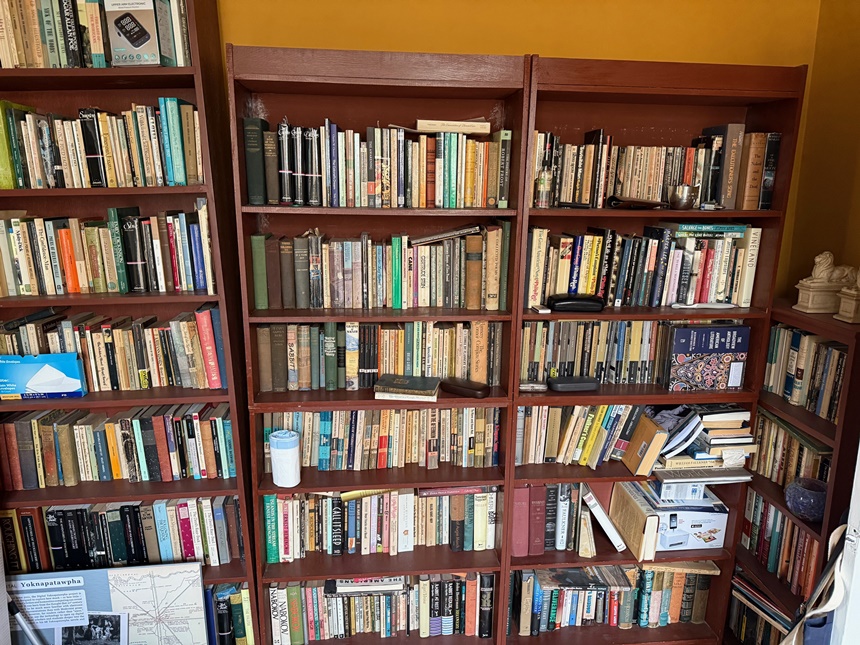

Over the final few decades of his life Steve also became a groundbreaking contributor to an essential new form of public scholarship, one designed to connect students and educators at all levels (as well as interested American audiences) to our literary, cultural, and historical traditions. These were his trio of pioneering digital humanities web projects: Mark Twain in His Times, a site dedicated to the works, life, and contexts of America’s most iconic author; Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture, a site focused on the monumental influence of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel and its many adaptations across the last two centuries; and Digital Yoknapatawpha, a site that combines cutting-edge technology with Steve’s innovative ideas to map both William Faulkner’s fictional Mississippi county and his collected works.

I could write about all three of these web projects for many more paragraphs, but I’ll end by highlighting one particular section of the Digital Yoknapatawpha project: the Getting Started and Demo videos. That’s my dad’s voice narrating the videos, patiently and helpfully guiding students, educators, and audiences of all types through the many ways they can use the site’s technologies and resources (it’s also one of the only places I’ve found where I can still hear his voice, so a place to which I’ve returned a good deal since March 2nd). This was his third and final web project, one started right at the end of his teaching career and built during his retirement, and it would have been more than understandable if he had handed off these videos to the project’s technologists or its other faculty collaborators. But he was far too much of a lifelong educator, far too committed to doing everything he could to support students and teachers and learning, not to lend his own voice to these vital resources. One more of the countless ways Steve Railton embodied the best of American education.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now